Preparing for shocks through Universal Basic Income: Evidence from Kenya

This post was originally published on African Arguments on January 20, 2022, and is part of an ongoing series. Read the other blogs in the series on obstacles to accurately identifying those in need of social assistance; the benefits and challenges of digital IDs; increasing girls’ enrollment in school; and how different electricity billing systems may impact energy access.

Covid-19 pushed an additional 100 million people into extreme poverty, according to the World Bank. The pandemic has not only caused a global health crisis, but also has led to major economic disruptions. The disease has claimed millions of lives globally, including thousands dying of starvation, lack of access to medical care due to income losses, and illness because of exposure due to inability to isolate as people need to work to sustain their household.

Governments and civil society, realizing the effect the pandemic and recession are having on people, have responded with a large increase in the number and reach of social protection programmes, including cash transfers, in-kind grants, subsidies and school feeding programmes. As climate change becomes an increasingly scary reality, it is important to explore to what extent and how we plan for large shocks. Do the effects of pre-existing social assistance programmes persist during a health and economic shock? What about a universal basic income – could that be a solution to unanticipated shocks?

What is a universal basic income (UBI)?

A universal basic income (UBI) is a specific form of social protection: an unconditional cash transfer large enough to meet the basic needs of individuals and delivered to everyone within a community. The idea of a UBI has been around for decades and of late has been gaining traction globally, with pilots launched in several countries including India, Finland, and the US among others. A poll conducted in Europe last year found that 64 percent of those surveyed were in favour of a UBI and this increased to 68 percent if respondents consider the current pandemic in their response.

The narratives for a UBI are slightly different depending on the context. High income countries see a UBI as a means to deal with the disruption caused by automation and allow for more leisure. On the other hand, in lower income countries a UBI is seen as a way to effectively reach all those in need of support and reduce poverty.

In the developing world, there are many arguments for and against a UBI. For one, UBI does not rely on targeting (i.e. identifying specific individuals within a community to receive the transfer) which in practice can be difficult due to lack of accurate, holistic, and/or frequently updated data. The lack of suitable data could result in exclusion of a large number of deserving beneficiaries, particularly in lower income countries. Further, targeting creates potential for cronyism by those in power at the cost of those who might be more deserving.

Another argument put forth by advocates of a UBI is that it provides a form of insurance against unpredictable risks with unknown effects (such as an unanticipated global pandemic or natural disaster). As the pandemic, and likely other large natural shocks, affect people across income groups and location, in addition to the broader economy, one could argue that non-targeted transfers may be more appropriate and could also kickstart the economy through increased investment, spending, and demand for products.

Further, universal schemes include a larger group of citizens than targeted schemes, who often have greater bargaining power than the poorest citizens. Since this affects everyone, it could be more politically acceptable. Also since a larger group – including those with more bargaining power than the poorest – is invested in the outcomes of a UBI, it could be held more accountable.

However, on the other hand, it is unclear if the positive effects of social protection transfers found during “normal times” will hold during the pandemic. Concerns around supply chain disruptions leading to lack of access to food and other necessities may limit the effectiveness of cash grants. Hence, any social protection measure including a UBI might be ineffective in the absence of other support such as food rations. Further, universal schemes will likely be costlier due to the increased number of people being covered. This is particularly true in cases where universalization is not coupled with self-targeting mechanisms and a reduction in expenditure on other social programmes. However, universalization could also reduce administration costs as targeting is not required. Finally, universalization could shift away the focus from the poorest and their needs.

Evaluating UBI in Kenya

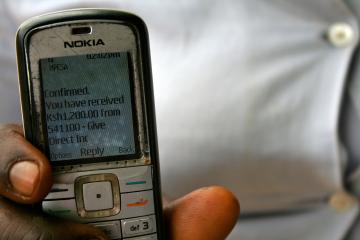

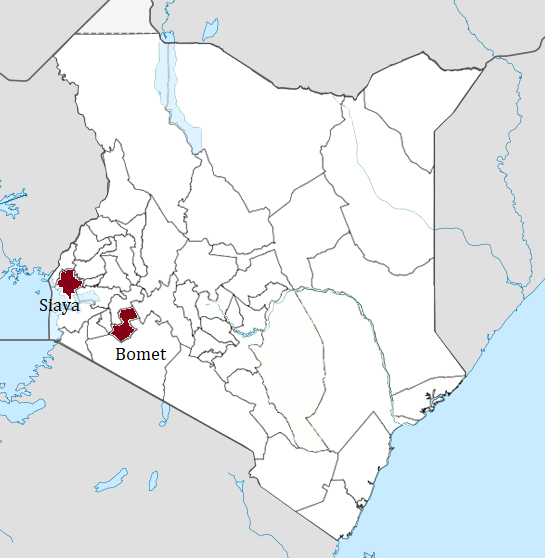

In 2017, Abhijit Banerjee, Michael Faye, Alan Krueger, Paul Niehaus, and Tavneet Suri, in collaboration with Innovation for Poverty Action (IPA) and GiveDirectly, launched a randomized evaluation in Kenya to test the effects of a digitally transferred UBI in two of Kenya’s low-income counties. The research took place in Siaya and Bomet Counties in Kenya, which have populations of 940,000 and 860,000 respectively. Approximately 630,000 people (roughly 35 percent of the population) in these counties are living below the Kenyan government’s poverty line.1

Participants, in the study, consisting of 14,474 households from 295 villages, were randomly assigned into one of four groups, three of which received digital cash transfers with varying frequency and size:

- Lump sum UBI: In 71 villages, approximately 8,800 people received a large lump-sum transfer (~US$500) at the beginning of 2018.

- Long-term UBI: In 44 villages, approximately 5,000 people received a smaller long-term transfer (US$0.75 per adult per day) scheduled to be received regularly for 12 years. This amount covered basic food and maybe some basic health and education related expenses.

- Short-term UBI: In 80 villages, approximately 8,800 people received a short-term transfer (US$0.75 per adult per day) for two years that had largely been concluded prior to the Covid survey.

- Comparison group: In 100 villages, approximately 11,000 people do not receive any transfer and make up the comparison group.

The Covid-19 pandemic unfortunately served as a unique opportunity to examine to what extent a UBI can mitigate the impact of a large shock. Against this backdrop, the researchers, funded by J-PAL Africa’s Digital Identification and Finance Initiative (DigiFI), conducted phone surveys in May and June 2020 to measure the effects of the pandemic on households and to assess whether the negative effects of the pandemic were mitigated by receipt of a UBI grant. To assess how outcomes have changed since the onset of the pandemic, they compared the data from the Covid survey to data from the pre-pandemic survey of households conducted between August and December of 2019.

In the absence of a UBI

During the pandemic and in the absence of a UBI, people (in the comparison group) experienced widespread hunger, sickness, and depression (measured using the standard Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)). Sixty-eight percent of adults who did not receive any UBI in this study reported experiencing hunger in the past 30 days. Forty-four percent of households had at least one member fall ill during the last 30 days, indicating a fairly unwell population. Given Covid-19’s very low prevalence at the time of the surveys (12 cases in total in Bomet and Siaya) these illnesses were almost surely something else. Twenty-nine percent of adults had been to a hospital and 44 percent were depressed. This highlights the condition of people during the pandemic in Siaya and Bomet counties in Kenya.

It is important to note that the hunger, illness, and depression, reported above, could be driven by agriculture seasonality and/or Covid-19. Kenya experiences a lean agriculture season, in which food is scarcer and more expensive in May–June, which coincided with one of the most severe lockdowns of the pandemic. This lean season could have led to the decreased income effects seen across both UBI beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. The researchers were not able to isolate the effects of the pandemic from effects of the lean season. However, the lean season is also a major shock as is Covid-19. As an argument for a UBI is that it protects against shocks, it is important to understand the effects of UBI against the shock experienced in May–June 2020 whether this shock was the agriculture lean season or the pandemic or a combination of both.

Effects of receiving a UBI: welfare, public health, and resilience

The UBI led to modest but significant effects on welfare. Beneficiaries of the UBI experienced less hunger, sickness and depression, both before and during the pandemic. However, prior to the pandemic, the UBI also led to increased investment in enterprises, earning of which fell during the pandemic and economic restrictions. The effects of the UBI are summarized below:

Hunger: 57–63 percent of beneficiaries that received a UBI were likely to experience hunger. This is a 7–16 percent reduction in experiencing hunger as compared to those that did not receive a UBI. The reduction was around twice as large for the long-term UBI beneficiaries and significantly different from those in the short-term and lump sum arms. Recipients of a UBI were also more likely to have a diverse diet, including eating meat/fish. That said, even in the long-term, the reduction in hunger is modest with the rate of hunger falling from 68 to 57 percent.

Illness: 38–42 percent of adults who received a UBI were physically ill. This is a decrease of 9–14 percent or 2–6 percentage points as compared to those that did not receive a UBl. Recipients were also significantly less depressed in the long-term and short-term. UBI recipients were 7–10 percent less depressed than non-recipients. Non-recipients scored an average of 16.05 on the CES-D scale and 44 percent were depressed.

Public health: The UBI appears to have impacted public health behaviours. Receiving a UBI led to reduced meetings among friends and relatives, though it did not change commercial interactions. Further, UBI beneficiaries were 3–5 percentage points less likely to seek medical attention, as compared to 29 percent who had sought medical attention in the comparison group. This is interesting and puzzling as evidence shows that transfers in “normal” times increase utilization of health services. However, these are not usual times. The decrease in seeking medical attention could be driven by households’ preference to reduce medical interactions during a pandemic and households with more financial resources being better able to do so. It may also reflect actual lower incidence of illness among households receiving a UBI or be driven by lower levels of depression among UBI recipients. Although not measured directly, the lower likelihood of seeking medical attention would have resulted in a decreased burden on hospitals, which could have been helpful in freeing up public health system capacity which has been crucial during the pandemic.

Income: Prior to the pandemic, some beneficiaries of a UBI diversified their income streams by starting non-agricultural enterprises. This is consistent with the idea that transfers induced beneficiaries to undertake relatively risky income-generating activities knowing that they had additional income to meet their basic needs. These beneficiaries saw large corresponding increases in profits from these enterprises before the pandemic. But when the pandemic and economic lockdowns hit, non-agricultural enterprise earnings fell by 71 percent from December 2019 to June 2020. While these non-agriculture enterprises remained operational for the most part, the income gains witnessed pre-Covid were wiped out. On net, UBI recipients thus saw their incomes fall more when incomes in general fell between late 2019 and early 2020, but saw hunger increase less.

UBI as a tool against unanticipated shocks

Access to a UBI before and during a large unanticipated shock, such as Covid-19, helped recipients’ well-being. However, UBI is unlikely to be a stand-alone tool of choice in such contexts. A UBI is likely to encourage risk-taking, as observed in Kenya with recipients’ pre-Covid investments in non-agricultural enterprises, and hence, may increase exposure to negative shocks. This is not a failure of a UBI – as by design it encourages risk to increase returns while providing a cushion for basic needs.

These results highlight the importance of access to income supplements, particularly to reduce hunger, exposure to the disease, and illness during a large shock. The results strengthen the case for social protection programmes and building infrastructure for cash transfer systems that can be activated at short notice and be used to deliver income support, in response to unanticipated crises.

End Note

1 Defined as less than US$15 per household member per month for rural areas, and US$28 for urban areas.

About the series:

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and Debating Ideas collaborative blog series – Unpacking the evidence of social programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa – seeks to contribute evidence-informed perspectives to debates around key questions in the fight against poverty. The material published as part of this blog series is based on J-PAL’s research network and is anchored by more than 225 affiliated researchers at universities around the world who are united in their use of randomized evaluations to identify the most effective approaches to reducing poverty and improving lives.