Connecting Egyptian Women to Gender-Based Violence Resources via Social Media during Covid-19

- Women and girls

- Adults

- Gender attitudes and norms

- Attitudes and norms

- Gender-based violence

- Digital and mobile

- Information

- Social networks

- Norms change

- COVID-19 response

- Edutainment

- Media

Restrictions on movement, social isolation, and economic stress resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic have increased women’s exposure to gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV), including in Egypt, and made it more difficult for them to access in-person resources. Researchers partnered with the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights to evaluate the effect of educational social media and TV campaigns on women’s attitudes and behaviors around responding to GBV and IPV. WhatsApp was more effective than Facebook in delivering the content, and equally as effective as TV. Irrespective of the specific platform, the social media campaign increased women’s knowledge and use of resources, but had no impact on their underlying attitudes towards gender equality or gender-based violence.

Policy issue

During the Covid-19 pandemic, women—particularly in the Global South—have become increasingly exposed to gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV), due to restrictions on movement, social isolation, and economic stress. Given social distancing, women without previous knowledge of resources—such as organizations that can counsel them on safely responding to violence—may be especially vulnerable. At the same time, pandemic restrictions also make it harder for women impacted by violence to access in-person support, highlighting the need for these organizations to find alternative ways to connect with them.

Curbing violence requires shifting norms that accept violence, remedying the economic and political marginalization of women, and supporting public engagement and advocacy. In particular, previous research has shown that media and “edutainment” (educational entertainment) campaigns can be successful in reducing violence against women. Exposure to role models or dramatized content may capture individuals’ attention, motivate shifts in behavior, and—when edutainment is shared on the community level—even shift perceptions of social norms. This evidence is somewhat mixed, however, and there is little evidence on whether social media platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp can be effective in delivering edutainment interventions, which are typically shared through traditional film distribution or in-person gatherings.

Context of the evaluation

Egypt has high levels of gender inequality and gender-based violence, ranking 129th out of 153 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Gender Gap Index. As of 2015, 36 percent of ever-married women between the ages of 15 and 49 in Egypt reported having experienced physical domestic violence, but only one-third sought help and only 18 percent reported it. Low levels of reporting reflect, in part, social norms that justify violence and blame women for its occurrence, as well as the challenges of navigating Egypt’s legal system.

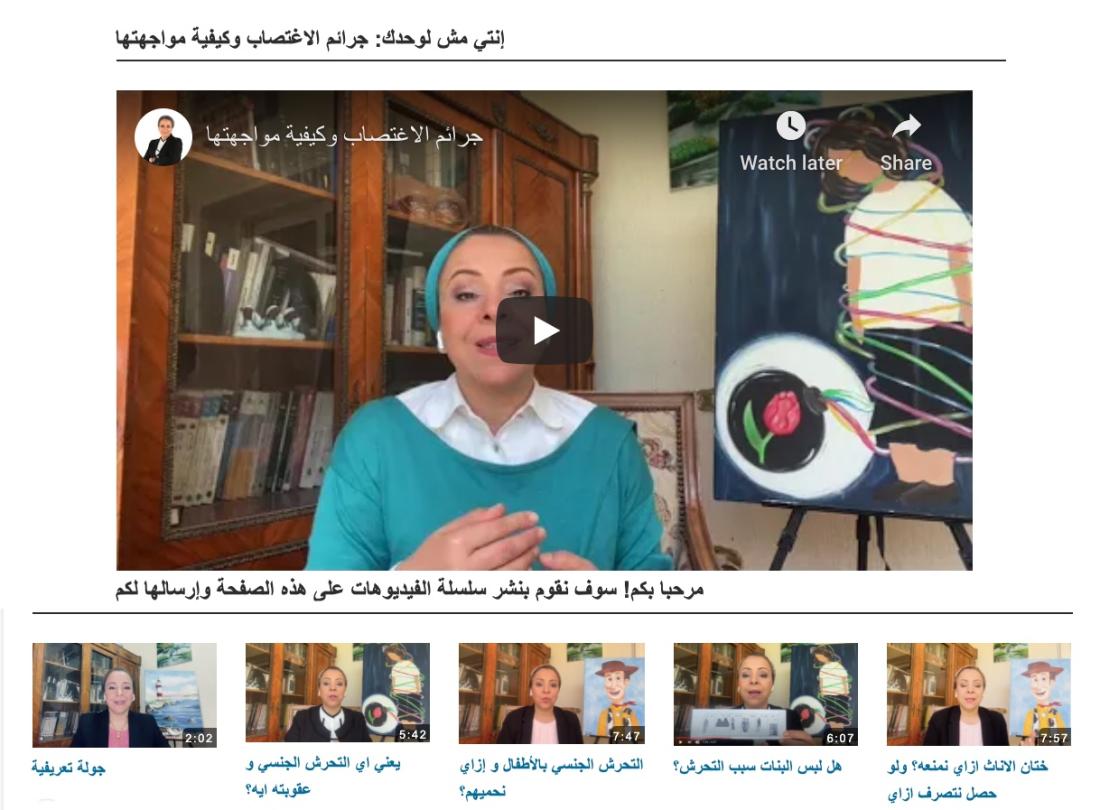

While Egyptian women face barriers to reporting violence directly to authorities, they can access advocacy organizations, such as the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights (ECWR). ECWR provides media programs, hotlines, and legal advocacy that seek to shift norms around violence and provide resources to women impacted by it, including legal support. The organization and its founder, Nehad Aboul Qomsan, use social media and TV to disseminate their content to women.

Between June and September 2020, ECWR released two sets of videos in which Aboul Qomsan addresses patriarchal norms, emphasizes that women are not to blame for violence, encourages friends and family to support survivors, and discusses ECWR’s resources. The first set of videos comprised the latest season of a weekly TV show called Hekayat Nehad (Nehad’s Stories), which aired on Saturday evenings and ran from 25 to 30 minutes. The second set of videos ran from five to nine minutes and were intended for dissemination over social media.

Women in the study were more likely to come from densely populated governorates in Egypt, particularly from Cairo. At the start of the evaluation, only 28 percent of women surveyed knew of any online resources and 22 percent knew of organizations available to support women affected by GBV.

Details of the intervention

Researchers partnered with the ECWR to evaluate the impact of disseminating content designed to shift norms around gender-based violence and provide support to survivors via Facebook, WhatsApp, and television.

Using Facebook advertisements, researchers recruited 9,431 Egyptian women to take a survey. through which 5,618 women elected to receive additional information and videos about women’s rights. Researchers randomly assigned women who elected to receive additional information to one of the following groups:

- TV reminder (952 women): Participants received WhatsApp messages each Saturday reminding them about the time and channel of the show Hekayat Nehad, which covered topics related to women’s empowerment and violence against women.

- WhatsApp Individual (1,118 women): Participants received weekly links to a series of short videos covering similar material to the Hekayat Nehad series, via individual WhatsApp messages.

- WhatsApp Group (1,879 women): Participants received the same links to short videos in groups of eight to twelve other users. Delivering content in groups may be more effective in changing attitudes and behaviors than delivering it individually, by generating discussions conducive to shifting individuals’ beliefs about social norms.

- Facebook Individual (565 women): Participants received links to the first four short videos via Facebook’s Custom Messages Channel. Due to technical issues, participants received the remaining links via individual WhatsApp messages. Researchers analyzed the results for these participants jointly with those in the WhatsApp Individual group.

- Comparison (1,104 women): Women randomly assigned to the comparison group did not receive any of the WhatsApp or Facebook messages, instead receiving all intervention content after completing the endline survey.

The intervention took place over an eight-week period from July to September 2020. In a follow-up survey, which took place from September to October 2020, 4,165 respondents answered questions about their attitudes on violence, gender, and marital equality; reported and hypothetical use of resources in response to domestic or sexual violence; and beliefs about whether Egyptian women would achieve gender equality in the future. Researchers combined these survey responses to create indexes of women’s behaviors and beliefs.

In addition to receiving ethical review and approvals from an institutional review board, the research team took a number of measures to minimize risk to participants. Researchers decided to include only women in the study, primarily to reduce the risk of harassment in the WhatsApp Group intervention arm, as well as to reflect the urgency of reaching women amid Covid-19.

The research team sought to minimize the risks of re-traumatization in both the survey instruments and the intervention content, including by refraining from asking sensitive questions about respondents’ personal experiences with GBV or IPV. The enumerator team, in consultation with ECWR, also directly referred women to supportive resources upon request. For more on the researchers’ discussion of ethical considerations, see page 17 of the working paper.

Results and policy lessons

Women who received the videos or reminders to watch the TV show increased their knowledge of resources available to those exposed to gender-based violence, and their hypothetical and actual use of these resources, but there was limited evidence that the videos and reminders impacted underlying norms about gender equality or the acceptability of violence against women.

Consumption of information: Women in the intervention groups were more likely to report receiving and viewing the video or TV content, and were better able to accurately describe the content. Approximately 45 percent of women in the social media intervention groups visited the website hosting the videos, with the average visitor watching between two and three videos. The individual dissemination of videos was more effective through WhatsApp than through Facebook, with 0.126 more visits per assigned user contacted through WhatsApp.

Knowledge of resources: Women who received the videos or reminders to watch the TV show reported increased knowledge of resources for women experiencing violence. Relative to the comparison group, women who received TV reminders, individual WhatsApp or Facebook messages, or group WhatsApp messages increased their knowledge by 0.12, 0.23, or 0.30 standard deviations, respectively. There was no difference in knowledge acquisition between women who received the videos on WhatsApp or watched the TV show.

Use of resources: Across intervention groups, women reported being more likely to seek out online resources or to contact an organization in hypothetical scenarios of exposure to violence, an increase ranging from 0.08 to 0.10 standard deviations, relative to the comparison group. In addition, women who received the videos were more likely to report actual recent contact with an organization and use of these resources—an increase of 0.09 standard deviations in the TV reminder arm, 0.06 standard deviations in the Facebook and WhatsApp Individual arm, and 0.10 standard deviations in the WhatsApp Group arm, relative to the comparison group. However, women in the intervention groups did not report more domestic or sexual violence than women in the comparison group.

Attitudes on norms and violence: There is limited evidence that the interventions shifted individuals’ beliefs toward gender and marital equality, rejection of sexual violence, or willingness to donate to organizations supporting survivors of GBV. Researchers suggest that results underscore the stickiness of attitudes towards gender norms, which are reinforced by patriarchal cultural norms, prevailing religious interpretations, and economic structures like labor market barriers.

Future outlook: Despite having limited impact on women’s attitudes toward gender and marital equality, the interventions increased participants’ beliefs that women in Egypt would one day achieve greater gender and marital equality—except for women participating through WhatsApp Groups. This null result may be due to the absence of meaningful conversations in these groups.

These results are consistent with previous findings showing that edutainment may increase reporting of violence without impacting underlying attitudes. Relative to other dissemination methods, distributing edutainment content via social media or TV may particularly constrain discussion or perceptions that norms are shifting, limiting potential effects. Using social media can still be impactful, as these platforms are increasingly popular in Egypt and elsewhere, allow for low-cost dissemination, and circumvent mobility restrictions arising from Covid-19. Because men’s participation is critical to shifting norms and behaviors around GBV and IPV, future digital interventions and research should consider how to ethically include men.

ECWR drew from the results of the study to continue disseminating critical factual information regarding services to target populations.