Reforming Indonesia’s largest food assistance program: From Rastra to BPNT

On March 31, J-PAL Southeast Asia hosted a webinar to disseminate the preliminary findings from a study on the long-awaited transition from Beras Sejahtera or Rastra (previously known as Raskin), Indonesia’s largest food assistance program which covered 15.5 million beneficiaries, to non-cash food assistance or BPNT. The event attracted almost 900 participants, the majority of whom were representatives from the government sector and research institutions.

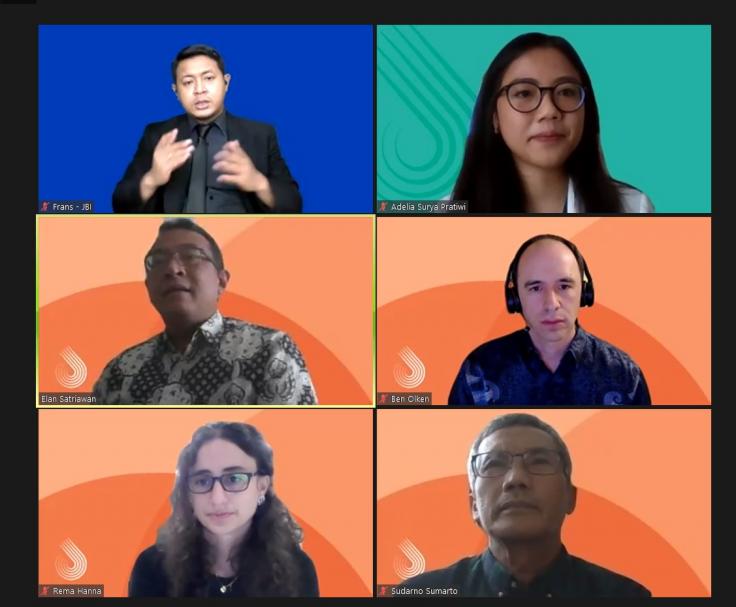

The webinar featured J-PAL SEA Co-Scientific Directors Rema Hanna (Harvard) and Ben Olken (MIT; Co-Director, J-PAL), Elan Satriawan (UGM; Chief of Policy Working Group, TNP2K ), and Sudarno Sumarto (SMERU Research Institute; Policy Advisor, TNP2K) who were involved first-hand in the evaluation process, along with Maliki (Director for Alleviating Poverty and Development of Social Welfare, Bappenas) who shared his view on how these findings could be used to further informed policies. The session was moderated by Adelia Surya Pratiwi (Head of Public Communications Strategy and Management Subdivision, BKF).

The session was also attended by Tb. A. Choesni (Deputy Ministry for Social Welfare Improvement, Kemenko PMK), Asep Sasa Purnama (Director General for Poverty Handling, MoSA), Vivi Yulaswati (Senior Advisor to the Minister of Development Planning for Social Affairs and Poverty Reduction, Bappenas), Ryan Washburn (Mission Director for Indonesia, USAID) and Simon Ernst (Counsellor, Development Effectiveness, Australian Embassy Jakarta), who participated as keynote speakers in the webinar.

The challenges of the Rastra program and the solution

The transition from Rastra to BPNT may be Indonesia’s largest social assistance reform in twenty years. Before the reform took place, beneficiary households used to receive 10 kilograms of free rice per month under the Bansos Rastra program. However, there were several complications with the in-kind transfer process, especially in terms of the quality and quantity of rice. For example, beneficiary households tend to receive less rice than what was originally intended—and often of poor quality. This was also coupled with various logistical challenges, such as delay in the delivery process or loss of rice due to leakage (e.g., when sacks of rice fell off the truck).

Looking at this situation, the Government of Indonesia, in collaboration with various international organizations and universities, conducted numerous studies on the Rastra program, which in the end resulted in the recommendation to transform the program delivery into a non-cash method, or BPNT.

Through this mechanism, instead of receiving assistance in the form of rice, beneficiary households will receive e-vouchers transferred to an account in their name, amounting to IDR 110,000 (USD 7.60) per month. The e-voucher can be accessed using a debit card, and can be used to purchase rice and eggs at any registered retailers, also known as agents or e-warongs. The ultimate goal is to create a more effective social assistance program, by improving what the Indonesian government refer as the “6T”: tepat sasaran, tepat harga, tepat jumlah, tepat mutu, tepat waktu dan tepat administrasi (targeting, price, quantity, quality, time and administration).

The decision to transition from in-kind food assistance to electronic food vouchers was a direction from President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo back in 2016, as explained by Tb. A. Choesni in his opening remarks. Following this mandate, in 2017 the government began to implement BPNT in stages. Nevertheless, the question remains on whether or not the BPNT program managed to overcome the challenges of Rastra. To answer this, the Government of Indonesia worked together with J-PAL affiliated researchers to conduct a randomized evaluation on both programs.

BPNT: A promising solution to Indonesia’s poverty challenges

In assessing the impact of the reform on individual welfare, researchers conducted an evaluation with the goal to compare the delivery of social assistance using BPNT and Rastra. The evaluation involved 105 districts, with 42 districts transitioning to BPNT in 2018 and 63 transitioning to BPNT in 2019.

Results show that not only was there better targeting in districts implementing BPNT, but the quality and amount of assistance received by beneficiaries also increased. This was possible because the vouchers managed to concentrate aid to truly eligible households, therefore decreasing the probability of non-poor households receiving the assistance.

On average, there was a 45 percent increase in the value of subsidies received by below-cutoff households in districts implementing BPNT. This increase in subsidy value also led to a decline in poverty—presumably because beneficiaries received a higher amount of assistance. For households that fall under the bottom 15th and 5th percentiles, poverty was 20 and 24 percent lower respectively.

The BPNT program also affected households’ consumption decisions. Under BPNT, each household can purchase eggs in addition to rice. However, as almost everyone in Indonesia consumed more than 10 kg of rice per month (the amount received under the Rastra program, and equivalent to the BPNT e-voucher), there was no mechanical reason to expect households to use the subsidy to purchase eggs.

And yet, the result shows that there was an increase in egg consumption, with no impact on overall rice consumption. This finding highlights a very important point, in line with the government’s efforts to further broaden the type of food under this program: having a wider range of food available can encourage beneficiaries to have a more diverse diet.

The last set of findings are related to the rice price and the administrative cost of the project. One of the key concerns of the government is whether there would be an increase in the price of rice in the districts implementing BPNT.

While economic theory predicts that this might happen (limited supply of rice in agents or e-warongs might drive the prices up), in reality, BPNT did not have a major impact on rice price. Although there was a slight increase in price in remote villages, it was not enough to negate the benefits of the program. Furthermore, the administrative cost of BPNT was even lower than the already low cost of Rastra: only 0.75 to 2 percent of benefits disbursed. BPNT was thus substantially less costly to administer, in addition to the fact that it was more effective in delivering assistance to targeted beneficiaries.

The continuous improvement of Indonesia’s social assistance program

Based on these the findings, the transition from Rastra to BPNT appears to be a one-way road, and the question now is how to optimize the program. According to Maliki, improving data quality is essential in ensuring a smooth program implementation, especially considering the government has a plan to further transform the social assistance program.

As of 2020, BPNT was upgraded into Program Sembako, which includes an e-voucher worth IDR 150,000 (USD 10.40) that can be used to purchase a wider range of food commodities, not only rice and eggs. In the future, the government is also planning to further transform this program into Program Sembako Plus, with the ‘Plus’ covering electricity and gas, aside from basic food needs.

To ensure the success of this long-term plan, having reliable beneficiary data is key. At the moment, there is still insufficient information especially on beneficiaries located in remote areas (i.e., missing ID card numbers, incomplete family names). This makes it harder to create a bank account, which is a fundamental part of the assistance. A continuous improvement of beneficiary data is thus highly recommended.

Moreover, a constant renewal of the socio-economic data of each beneficiary household is also crucial, especially to further increase the accuracy of the program targeting. By carrying out these two points, the ultimate goal is to digitize and integrate Program Sembako with other social assistance programs, in order to eradicate chronic poverty in 2024.