A well CAL-ibrated approach to addressing learning losses in a post-Covid classroom

Schools in India have been shut down since March 2020 due to Covid-19, compelling students to rely on mobile phones and laptops to take online classes. When schools reopen, students, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds and without access to these technological resources, might find themselves lagging behind in the classroom even more than they were in pre-pandemic times.

This will likely widen learning gaps now more than ever. In such a scenario, the onus falls on governments to devise strategies that can bridge learning gaps and improve learning once schools reopen.

One approach that can equip educators and, specifically, public school systems, to address these learning losses is by tailoring classroom instruction to students’ current learning levels, rather than by age or grade. Research from countries like Chile, India, Kenya, and the United States suggests that personalizing instruction can be one of the most effective ways of improving learning while making judicious use of existing educational resources.

There are multiple effective channels to deliver this evidence-based approach, one of them being Computer-Assisted Learning technology or CAL.

CAL is an ed-tech tool that can be highly cost-effective for low- and middle-income countries. It is classified as a “Good Buy” according to a new inter-disciplinary Global Education Evidence Advisory panel convened by the World Bank and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO)1 for—importantly—schools where hardware is already present and can be maintained.

So far, much of the evidence supporting the effectiveness of CAL is from high-income countries. But under the right conditions, in appropriate contexts, and if implemented well, it may be promising even for low-income countries. Evidence from countries like India indicates that this technology tool may have the potential to deliver tailored instruction in these unprecedented times.

Learning gaps in India’s post-COVID classrooms

Rukmini Banerjee of Pratham Education Foundation notes that due to prolonged school closures, learning losses in India due to the pandemic are likely to be deeper than the “summer loss” normally recorded after summer breaks in school. Therefore, as Indian schools reopen, educators will be faced with the mammoth task of helping students catch up.

Moreover, the government’s decision to promote students from classes 1 to 8 to the next grade, as well as the trend of parents moving their children from private to public schools due to financial distress, are poised to create an increased heterogeneity of learning levels within the same grade.

Compounding these challenges is the digital divide that has exacerbated learning gaps during the pandemic, especially in rural areas. Only 12.5 percent of Indian households have internet access, ranging from 27 percent in urban areas to 5 percent in rural areas.

Even among those who have access to laptops and smartphones, more than one in three students thought that online classes were burdensome, citing poor internet connections, difficulty in accessing content on phones, a lack of knowledge in using devices, untrained teachers, and erratic power supply as the major challenges they faced.

CAL: A promising solution

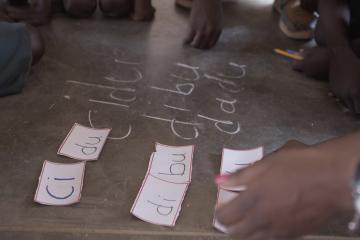

Dedicating a portion of classroom time to personalized and adaptive instruction is proven to be one of the most effective ways to minimize students’ learning gaps, and CAL offers a promising channel for delivering these customized lessons.

This ed-tech, software-based program adjusts lessons and activities to students’ current learning and achievement levels and in doing so, assesses learning gaps quickly, making it a useful supplemental tool in a post-Covid classroom.

One such software that is currently in use is Mindspark, which benchmarks initial learning levels by asking students a few preliminary questions and then dynamically personalizes learning material to match the level and rate of progress made by each individual student.

Evaluations of CAL programs, including Mindspark, have found promising results in both high- and low-income contexts. A review of more than thirty studies of CAL programs found that the software approach was particularly effective in improving students’ math outcomes.

Similarly, randomized evaluations conducted in India have found evidence that CAL technology, which interacts and adapts to students’ current learning and achievement levels, results in better grades in both math and language. A study of a Mindspark program in Delhi found that middle-school students enrolled in a CAL program scored better in math and Hindi over a period of only four to five months. These gains were much higher for academically weaker students.

Another CAL study conducted in India that emphasized basic competencies in math found that the scores of fourth-grade students in primary schools increased significantly in each of the program’s two years.

Randomized evaluations conducted in rural China found similar results. A CAL program in Qinghai, a rural province in China, resulted in increased language scores among minority students. Another study conducted in rural public schools in Shaanxi resulted in increased math scores, with students from disadvantaged groups benefiting the most.

At a time when educational resources may be scarce, technology-aided programs such as CAL show considerable promise. Customized learning material can help all students learn at their own pace and help teachers understand each student’s needs.

CAL, in particular, helps in providing faster feedback to teachers on a student’s progress, thereby offering a more responsive and adaptive channel to deliver tailored lessons in contexts where supporting hardware is already present.

Towards technology-aided tailored instruction

As governments in low-income countries increasingly consider technology-based solutions to bridge learning gaps, it is important to consider contexts in which ed tech has the greatest potential for delivering positive results in a post-Covid classroom.

CAL offers a promising tool for customized learning to help rebuild students’ foundational skills once schools reopen. However, for it to be effective as a “Good Buy,” it should be implemented in a way that is inclusive, that is, only where electricity, internet, teacher training, and hardware is already widely available.

According to the recently released report by the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel, if implemented poorly or in inappropriate contexts, investment in CAL is no longer cost-effective. While considering investments in technology aids for education, as important as it is to invest in hardware like laptops, computers, and tablets, it is essential for policymakers and educators to know how this hardware will be used, for whom, and also invest in proven software tools to deliver customized lessons to students.

In schools where appropriate inputs to implement CAL are not available, other strategies to deliver personalized and adaptive instruction can be adopted. However, schools will need to opt for policies that work best for them, rather than investing exclusively in ed-tech programs.

1Abhijit Banerjee served as co-chair of the Panel and J-PAL Education sector co-chair, Karthik Muralidharan was also a panel member.