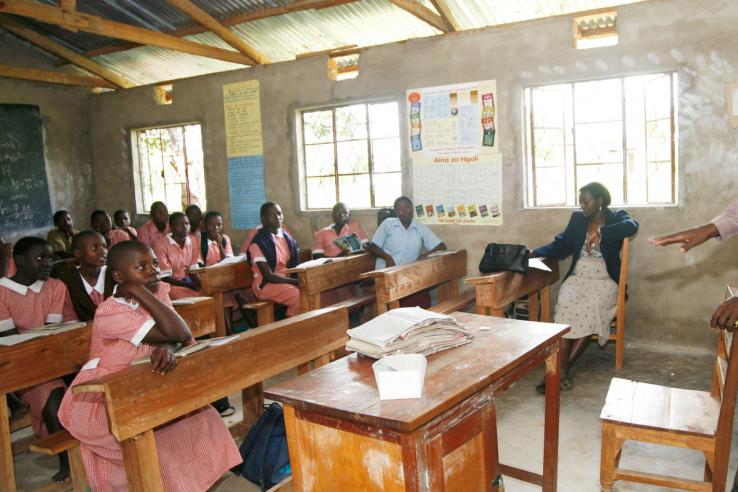

Increasing enrollment and attendance by making education benefits salient and changing perceptions

Summary

From 2000 to 2015, the portion of primary and secondary school age children enrolled in school worldwide rose from 83 to 91 percent and 55 to 65 percent, respectively [1]. However, pockets of low enrollment remain and millions of children who are enrolled are not attending regularly. Education requires an investment of time, money, and effort with many of the benefits coming far in the future. A range of programs have been evaluated which increase the salience of the benefits of attending school.

Nearly thirty randomized evaluations shed light on the link between the perception of education’s benefits and enrollment and attendance at school. Of the 30 studies, 21 studies deliberately tried to change salience, and nine studies allow us to examine whether changes in quality affected attendance. Interventions that successfully addressed perception gaps related to the benefits of education or increased student motivation or the salience of benefits had positive impacts on student enrollment and attendance. However, programs that improved the quality of education (as measured by test score improvements) did not typically increase participation, likely because parents and students find it hard to perceive changes in education quality. Even programs that visibly increased school inputs (such as buying new textbooks or computers), which might have signaled improving education quality to parents, did not usually translate into higher attendance.

Supporting evidence

Where misperceptions about the benefits of education exist, programs that address perception gaps or make the benefits more salient can change behavior at low cost. Over 40 percent of eighth-grade boys in the Dominican Republic did not expect their future earnings to be higher if they completed secondary school compared to only completing primary school [2]. Boys who received information on the average wages earned by people with different levels of education in their area completed an additional 0.2 years of schooling after four years. In Chile, providing information about how to access financial aid for further education increased student attendance in the short-run and led more students to enroll in college-preparatory high schools [3]. Changing perceptions of possible career opportunities for educated women by providing information on job opportunities led parents and students to invest more in their education in India [4]. Whether this strategy is useful locally will likely depend on existing levels of knowledge and the salience of the benefits of education. Where parents and children do not underestimate the benefits of education, or the benefits are already salient, providing information is unlikely to increase student attendance. In such cases, providing information could even reduce attendance if parents and students had overestimated the benefits of education, as was the case in China [5].

Improving education quality should increase the benefits of students and parents investing in education. However, quality is hard to perceive, so improving learning in schools does not always lead to higher participation, at least in the short term. As the quality of schooling is low in many developing countries, parents and children might conclude that sending kids to school is not worthwhile. On one hand, programs directly addressing education quality may reassure parents and children of the importance of attending school, in turn increasing participation rates. On the other hand, parents and students may find it challenging to judge the quality of education in the short term. Of nine evaluations of programs that successfully improved learning in schools (as measured by test score improvements) and also measured student attendance, four improved student participation in the short run [8][9][10], while five interventions did not change participation, at least in the short run [6][7][8][11]. Further study is needed to examine the longer-term impacts of improvements in education quality on student attendance.

Even when governments and others spend more money on schools in highly visible ways, such as by providing more textbooks and computers, this does not reliably prompt children to spend more time in school. A variety of programs provide school inputs, such adding textbooks or computers or improving libraries. Adding these inputs may signal to parents or students better school education quality and potentially lead to increased enrollment or attendance. However, inputs that may be perceived as making schools more attractive have not typically affected attendance. This includes programs in Kenya [12], Sierra Leone [13], Peru [14], India [15], and Bolivia [16].

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2018. "Increasing enrollment and attendance by making education benefits salient and changing perceptions." J-PAL Policy Insights. Last modified April 2018. https://doi.org/10.31485/pi.2263.2018

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics. Accessed July 21, 2017. Dataset

Jensen, Robert. 2010. “The (Perceived) Returns to Education and the Demand for Schooling.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (2): 515-548. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Dinkelman, Taryn, and Claudia Martinez. 2014. "Investing in Schooling in Chile: The Role of Information About Financial Aid for Higher Education." The Review of Economics and Statistics 96 (2): 244-257. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Jensen, Robert. 2012. "Do Labor Market Opportunities Affect Young Women's Work and Family Decisions? Experimental Evidence from India." Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (2): 753-792. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Loyalka, Prashant, Chengfang Liu, Yingquan Song, Hongmei Yi, Xiaoting Huang, Jianguo Wei, Linxiu Zhang, Yaojiang Shi, James Chu, Scott Rozelle. 2013. "Can information and counseling help students from poor rural areas go to high school? Evidence from China." Journal of Comparative Economics 41 (4): 1012–1025. Research Paper

Duflo, Esther, Rema Hanna, and Stephen P. Ryan. 2012. "Incentives Work: Getting Teachers to Come to School." American Economic Review 102 (4): 1241-78. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Banerjee, Abhijit, Shawn Cole, Esther Duflo, and Leigh Linden. 2007. “Remedying Education: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments in India.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (3): 1235-1264. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summaries (Computer-Assisted Learning), J-PAL Evaluation Summary (Tutoring)

Duflo, Esther,Pascaline Dupas, andMichael Kremer. 2015. "Education, HIV and Early Fertility: Experimental Evidence from Kenya."American Economic Review105 (9): 2757-2797. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, and Asim Ijaz Khwaja. 2017. "Report Cards: The Impact of Providing School and Child Test Scores on Educational Markets." American Economic Review 107 (6): 1535-63. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Barr, Abigail, Frederick Mugisha, Pieter Serneels, and Andrew Zeitlin. 2012. “Information and Collective Action in the Community Monitoring of Schools: Field and Lab Experimental Evidence from Uganda.” Unpublished manuscript, University of Nottingham. Research Paper

Pradhan, Menno, Daniel Suryadarma, Amanda Beatty, Maisy Wong, Arya Gaduh, Armida Alisjahbana, and Rima Prama Artha. 2014. “Improving Educational Quality through Enhancing Community Participation: Results from a Randomized Field Experiment in Indonesia.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6 (2): 105-126. Research Paper

Glewwe, Paul, Micahel Kremer, and Sylvie Moulin. 2009. “Many Children Left Behind? Textbooks and Test Scores in Kenya.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (1): 112–135. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Sabarwal, Shwetlena, David K. Evans, and Anastasia Marshak. “The Permanent Input Hypothesis: The Case of Textbooks and (No) Student Learning in Sierra Leone.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7021, September 2014. Research Paper

Cristia, Julian, Pablo Ibarrarán, Santiago Cueto, Ana Santiago, and Eugenio Severín. 2017. "Technology and Child Development: Evidence from the One Laptop per Child Program." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics9 (3): 295–320. Research Paper

Borkum, Evan, Fang He, and Leigh L. Linden. “The Effects of School Libraries on Language Skills: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial in India.” NBER Working Paper 18183, June 2012. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Newman, John, Menno Pradhan, Laura B. Rawlings, Geert Ridder, Ramiro Coa, and Jose Luis Eva. 2002. “An Impact Evaluation of Education, Health, and Water Supply Investments by the Bolivian Social Investment Fund.” World Bank Economic Review 16 (2): 241-74. Research Paper

Beasley, Elizabeth and Elise Huillery. “Willing but Unable: Short-Term Experimental Evidence on Parent Empowerment and School Quality.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8125, June 2017. Research Paper | J-PAL Evaluation Summary

Blimpo, Moussa P., David K. Evans, and Nathalie Lahire. “Parental Human Capital and Effective School Management: Evidence from The Gambia.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7238, April 2013. Research Paper