Changing resumes to reduce hiring discrimination

Summary

There is strong evidence of discrimination against a large number of different minority1 and underrepresented groups in labor markets in many countries. One of many strategies being tested, removing some information from resumes could reduce discrimination in the first stage of the hiring process by limiting employers’ opportunities to screen out applicants based on name, photo, criminal background, or other identifying information.

This insight draws from 23 randomized correspondence studies2 that measure the extent of hiring discrimination in different markets and two evaluations that use randomization to identify the impact of removing identifying information from job applications. In these two evaluations, removing information increased discrimination, with researchers pointing to different mechanisms to explain why. In the first evaluation, the removal of this information made firms that otherwise already interviewed and hired more minority candidates less likely to do so. In the second, employers shifted discrimination to other characteristics. However, since it is well-documented from correspondence studies that the average firm in many contexts discriminates, mandatory anonymization and other strategies that change the way employers review applications should be tested further.

Supporting evidence

Rigorous research points to considerable discrimination in labor markets against a range of minority groups across many countries. Correspondence studies, which send fictitious resumes to job openings, have found strong evidence of widespread discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, immigration status, gender, religion, and sexual orientation. Randomized studies that took place in thirteen countries found discrimination in 27 out of 31 comparisons [1][2] [3][4] [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]. For example, a 2004 study in the United States found that applicants with white-sounding names were invited for job interviews 50 percent more often than equally qualified applicants with black-sounding names[7].3 One possible explanation for these results is that some employers may have stopped reading a resume whenever they saw a black-sounding name, never reaching that candidate’s qualifications.

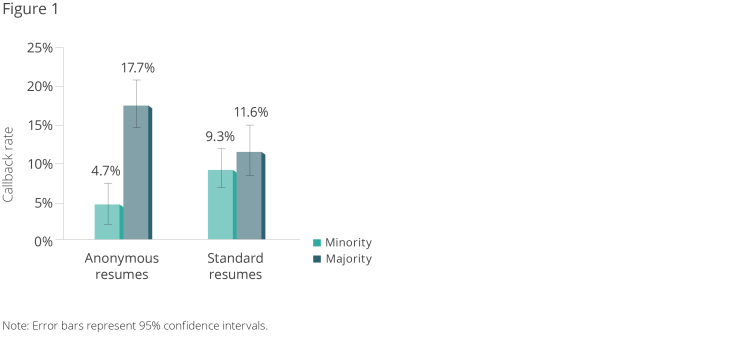

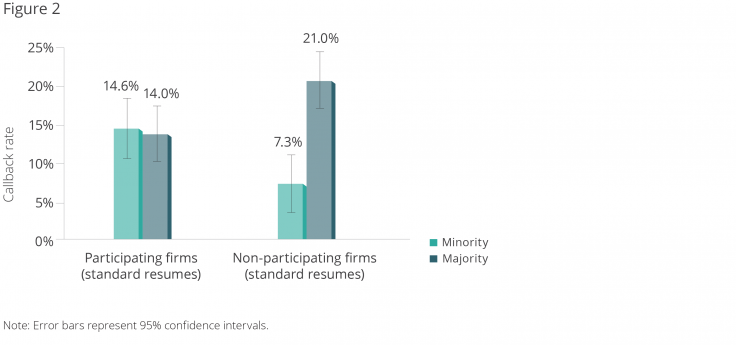

The impact of anonymizing resumes seems to depend on the characteristics of the firms that received the anonymous resumes, namely whether they were discriminating against minority groups in the first place. An evaluation in France of anonymous resumes looked at the impact on firms that had volunteered to participate[26]. These firms were previously more likely to interview and hire minority candidates. Within this group, firms that received anonymous resumes interviewed and hired fewer minority candidates. In this case, removing information on minority status prevented the firms from favorably considering minority applicants. Since it is well-documented that the average firm in many contexts discriminates, mandatory anonymization might capture those firms who would not voluntarily anonymize their screening process and produce different results.

In France, participating firms were less likely to hire minority candidates with anonymous resumes (Figure 1), but firms participating in the study who were in the comparison group (received standard resumes) were more likely to hire minorities than non-participating firms (Figure 2).

Removing information on some characteristics might change the way firms review resumes and lead them to discriminate on other characteristics correlated with minority status. A study in the United States found more discrimination against black applicants after the implementation of a policy banning employers from asking about criminal histories on job applications [24]. Researchers suggest that when employers lacked individualized information about criminal history, they tended to generalize that black applicants were more likely than white applicants to have criminal records. Through similar channels, anonymization might have unintended effects on how employers review resumes in other contexts. For example, removing information could prevent firms from considering negative signals, like unemployment spells, in light of hardships that a minority candidate might have experienced [26].

Mandatory anonymization and other strategies that change the way that employers review applications should be tested. Given that in many contexts the average firm discriminates, mandatory anonymization might reduce discrimination by capturing firms who would not voluntarily anonymize their application review and may be more likely to discriminate. Since research suggests that some employers exercise “attention discrimination,” in which they pay less attention to applicants with minority-sounding names [25] mandatory anonymization and other solutions that counter this attention bias should be evaluated. Other potential solutions could include changing the order of information on a resume so that someone’s minority status is not revealed until the employer has read the candidate’s other information. More research is needed to understand how anonymization changes the way firms review resumes and how to reduce discrimination during subsequent stages of the application process. Future policies should also consider the net impact on discrimination against minorities by capturing both firms who were discriminating and those who were more likely to interview and hire minority applicants before the policy change.

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2019. "Changing Resumes to Reduce Hiring Discrimination." J-PAL Policy Insights. Last modified February 2019. https://doi.org/10.31485/pi.2233.2019