The Impacts of In-kind Food Transfers versus Electronic Vouchers on Poverty Reduction in Indonesia

- Men and boys

- Rural population

- Urban population

- Women and girls

- Social service delivery

- Social protection

When implementing targeted food programs, governments often choose between providing in-kind transfers or vouchers, which differ widely in their administration. In partnership with the Government of Indonesia, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to compare the efficacy of vouchers versus in-kind transfers in reducing poverty and improving program delivery. The change from in-kind food transfers to vouchers led to an increase in assistance received by eligible households, due to improved targeting. As a result, poverty fell by 20 percent among the poorest households.

Policy issue

Targeted food programs, which provide nutritional support to low-income households, are among the most common type of social welfare programs globally.1 Governments often administer food assistance programs by either providing households with in-kind transfers of free or subsidized food, or by providing vouchers, which can be used to buy food on the market. These approaches may differ in their potential impact on local markets and in the delivery of aid in practice.2 Vouchers tend to offer more flexibility for beneficiaries’ consumption choices, while in-kind transfers may lead households to consume more of the provided items than they would otherwise purchase with a voucher. In-kind food transfers also increase the local supply of provided items, while voucher programs only directly impact household demand, which could affect local prices differently.

Moreover, a government’s ability to administer the program on the ground can also vary greatly, especially in areas with low state capacity. Vouchers and in-kind transfers present different logistical challenges including connectivity, authentication systems, or the local government’s control over how resources are distributed. What is the effect of moving from an in-kind program to an electronic voucher-based program on the delivery of aid and poverty reduction in a setting with limited state capacity?

Context of the evaluation

In 2017, Indonesia began to reform its largest in-kind food assistance program, Rastra, by replacing it with a voucher program, the Non-Cash Food Assistance (Bantuan Pangan Non-Tunai or BPNT), later known as Program Sembako. The reform took place over four years.

The Rastra program provided subsidized food assistance to 15 million households every month. Eligible households received 10kg of free rice per month, which was distributed by the local level officials. The subsidy was valued at approximately IDR 97,000 (US$7) and represented approximately 6.5 percent of the poverty line considering a household of 4 people. Under BPNT, households received a monthly voucher of IDR 110,000 (US$8) per month, added to a debit card issued to the female adult in the household. They could redeem the value for rice and eggs at any registered retailer, or save the voucher for future months, which was uncommon in practice.

The central government identified eligible households for Rastra through proxy-means testing (PMT), used to predict household’s consumption by collecting information about households’ assets and composition (see more information on the researchers’ separate study on PMT and targeting here). In order to receive the transfer, households needed to score below a certain threshold on the PMT (smaller or equal to 30).

The transition to electronic vouchers was intended to solve challenges faced by the Rastra program, such as many ineligible households obtaining rice while other eligible households received only a portion of the rice they were entitled to.3 Rastra was also characterized by high levels of leakages4 and low quality of rice.5 By moving to electronic vouchers, the government aimed in part to increase households’ satisfaction with the program by improving rice quality and food diversity, as households could also buy eggs.

Details of the intervention

In partnership with the Government of Indonesia, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to compare the efficacy of vouchers versus in-kind transfers in reducing poverty and improving program delivery. In 2018, during the second phase of the reform, budget constraints prevented the government to follow the plan of converting 105 new districts from Rastra to BPNT. This allowed researchers to randomly assign 42 of these districts to receive BPNT that year, while the remaining 63 districts were assigned to receive the program in 2019—serving as a comparison group. This resulted in a sample of 53 million individuals and about 3.4 million beneficiary households –about a fifth of Indonesia’s population.

Researchers used administrative data, including the Indonesian national household survey (SUSENAS) from March 2018 and 2019, to collect information on program recipients, household consumption, as well as poverty measures. In addition, they created a special social protection survey module, which asked if households had received the Rastra or BPNT program, as well as the amount, price, and quality of subsidized rice and eggs.

Results and policy lessons

The change from in-kind food transfers to vouchers increased the amount of assistance received by eligible households due to improved targeting. The government could better enforce the voucher program as designed, ensuring aid reached eligible beneficiaries and was not redistributed to ineligible households nearby, which was hard to prevent under the in-kind program. As a result, poverty fell by 20 percent among the poorest households. Vouchers also allowed households to purchase higher-quality rice, and led to increased consumption of egg-based proteins.

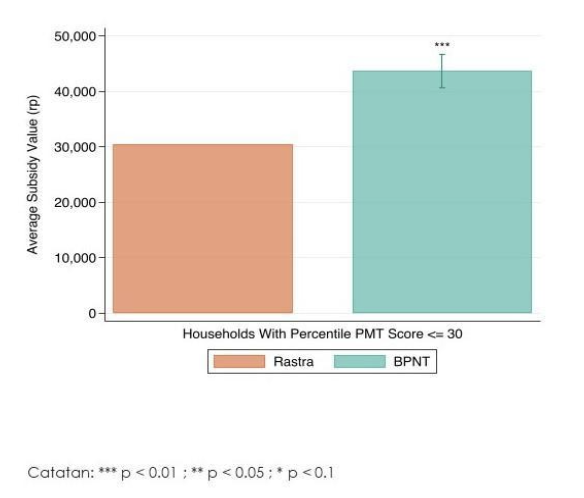

The change from in-kind transfers to vouchers changed the distribution of aid. In voucher areas, most households that received the program received the full subsidy amount. Among households that received the benefit, the average amount received in BPNT areas was IDR 112,000 (US$8), compared with IDR 67,000 (US$4.8) in Rastra areas, where the full in-kind entitlement would have been equivalent to approximately IDR 97,000 (US$7). This suggests that the voucher program was implemented with greater fidelity to program design by more often delivering the full amount beneficiaries were entitled to, at least among households that received any assistance.

The voucher program increased the value of subsidy received among the poorest households. On average, eligible households in BPNT districts received 46 percent more in subsidy relative to eligible households in in-kind districts. Participant households in voucher districts received IDR 13,496 (US$0.96) additional per month, compared to IDR 29,219 (US$2.09) per month in in-kind districts.

The BPNT voucher improved the targeting of the food assistance program. Relative to the in-kind distribution, vouchers helped concentrate aid to eligible households. There was a reduction in the number of people who received any subsidy under BPNT, but the reduction was larger for those who were above the eligibility cut off. For eligible households in voucher areas, the probability of receiving any assistance fell by 16 percent (10.5 percentage points from a comparison group average of 66.9 percent). However, for ineligible households, the probability of receiving assistance dropped by 49 percent (a 14.5 percentage points decrease from a comparison group average of 29.3 percent). Together, this means that households across the income distribution were less likely to receive assistance under the voucher program, especially ineligible households, but those who did receive assistance received substantially more than in in-kind districts.

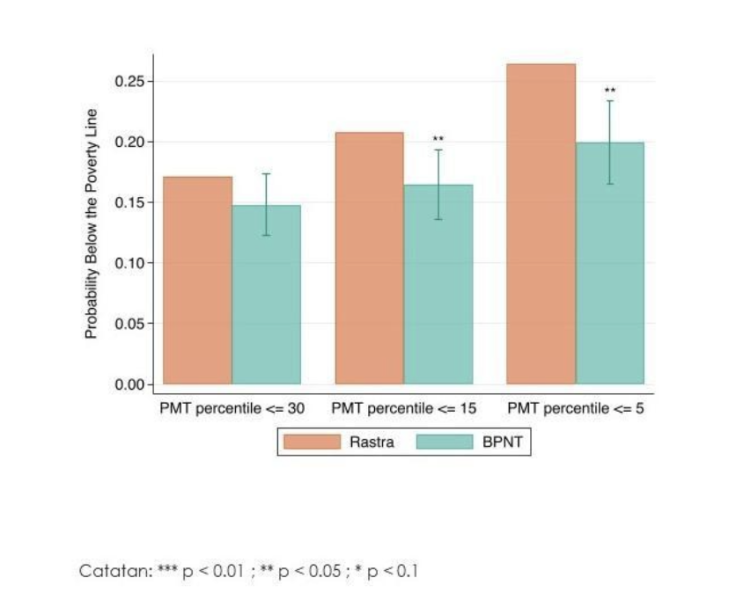

The reform reduced poverty among poor and near-poor households. The increase in the assistance received reduced poverty among low-income households. For the bottom 15 percent of the population, the BPNT program reduced poverty by 20 percent (or 4.3 percentage points from an average of 21 percent in the comparison group). The reduction in poverty was even greater for the very poorest households, who experienced a 24 percent reduction in poverty (or 6.5 percentage points reduction from an average of 26.7 percent in the comparison group). Poverty reductions appear to come from a shift in how aid was distributed, not from reductions in overall leakage levels.

The reform was also effective in improving the quality of rice received. Recipient households rated the quality of voucher rice 20.3 percentage points higher compared to a 63 percent quality rating for in-kind rice (a 32 percent increase). The quality improvements in the voucher program were likely a result of households having more flexibility to choose where they could get the rice from, instead of it coming from only one provider as in the in-kind transfer.

Households who received vouchers consumed more egg-based proteins. The BPNT transition did not affect the total amount of rice consumed, but it increased households’ eggs consumption. Eligible households in the intervention group consumed 9.3 more grams of egg protein compared to an average of 213.7 for households in the comparison group (4.3 percent increase), without changing overall rice consumption. Egg protein consumption increased the most for the poorest households (by 11.7 percent) and their overall consumption increased more. Moreover, researchers suggest that the impacts were driven by the addition of eggs to the set of goods the program participants could purchase, rather than a general increase in income.

Aggregate rice price was not affected, although in remote villages it increased modestly. Overall, there was no observable impact on the average rice prices, except for the most remote villages, where the voucher led to a 3.5 percent increase in prices compared to areas with in-kind transfers. However, this was not enough to disprove the gains from the BPNT program, as the rise in overall rice expenditure in these remote villages was lower than the increase in benefits received by eligible households.

The administrative costs were low for Rastra, but they were even lower for BPNT. The administrative costs of the Rastra program corresponded to about 4 percent of the benefits disbursed. Meanwhile, the total administrative costs of BPNT were between 0.7 to 2 percent of the benefits disbursed.

Administrative differences between in-kind transfers and vouchers are an important dimension for decision-makers to account for when considering different designs of social protection programs. How social programs are administered may be particularly relevant for program effectiveness in low state capacity settings.

The Government of Indonesia continued the reform to expand coverage of the BPNT program (now known as Program Sembako), reaching over 18.8 million households across the country, and increased the voucher amount to IDR 200,000 (US$14.3) in 2020. The result of the research provided evidence for the government to move forward with the digitization of the social protection system and the involvement of financial service providers in the social protection program delivery.

World Bank, 2018. “The State of Social Safety Nets 2018”. Washington, DC: World Bank. World Bank. https:// https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29115 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO

Cunha, Jesse M., Giacomo De Giorgi, Seema Jayachandran. 2019, “The Price Effects of Cash Versus In-Kind Transfers”. The Review of Economic Studies, 86 (1): 240-281

Banerjee, Abhijit, Rema Hanna, Jordan Kyle, Benjamin A. Olken, and Sudarno Sumarto. 2018. “Tangible Information and Citizen Empowerment: Identification Cards and Food Subsidy Programs in Indonesia.” Journal of Political Economy, (126) 2: 451-491.

Olken, Benjamin A. 2006. “Corruption and the Costs of Redistribution: Micro Evidence from Indonesia.” Journal of Public Economiccs, 90 (4-5): 853-870

Banerjee, Abhijit, Rema Hanna, Jordan Kyle, Benjamin A. Olken, and Sudarno Sumarto. 2019. “Private Outsourcing and Competition: Subsidized Food Distribution in Indonesia.” Journal of Political Economy, 127 (1): 101-137.