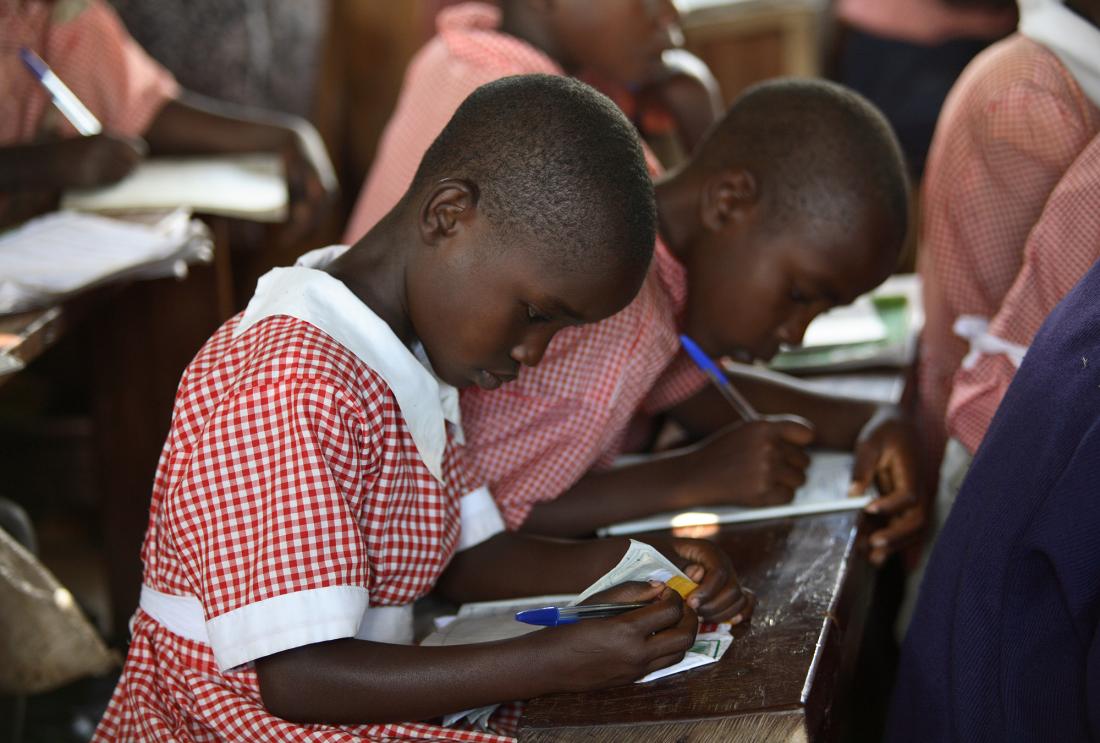

Incentives to Learn: A Merit-Based Girls' Scholarship Program in Kenya

- Children

- Parents

- Primary schools

- Students

- Women and girls

- Dropout and graduation

- Student learning

- Women’s/girls’ decision-making

- Scholarships

- Monetary incentives

Approximately 85 percent of primary school age children in western Kenya are enrolled in school, but only about one-third of students finish primary school. Dropout rates are typically higher for girls; in 2001 the 6th grade dropout rate was 10 percent for girls and 7 percent for boys among students in this study’s comparison schools at baseline. This project was introduced in part to assist families of high-achieving girls to cover the cost of school fees, supplies, and activities.

Policy issue

In many education systems, those who perform well on exams covering the material of one level of education receive free or subsidized access to the next level of education. Such merit-based scholarships are attractive to the extent that they can induce greater student effort, assuming that pupils are motivated to strive for scholarship opportunities. However, the role of student motivation in improving education outcomes is relatively poorly understood. Policymakers have frequently focused their attention on increasing schoolinputs or improving teacher attendance, assuming that students are motivated to take advantage of these improvements. Merit-based scholarships for girls may offer an alternative to increase female education, and more educated women tend to have healthier children and higher incomes. However, the assumption that pupils are inherently motivated to pursue education, and the effect that educational opportunities can have on female learning, are relatively unexplored.

Context of the evaluation

Approximately 85 percent of primary school age children in western Kenya are enrolled in school, but only about one-third of students finish primary school. Dropout rates are typically higher for girls; in 2001 the 6th grade dropout rate was 10 percent for girls and 7 percent for boys among students in this study’s comparison schools at baseline. Primary schools charge fees to cover their non-teacher costs, including textbooks for teachers, chalk, and classroom maintenance (approximately US$6.40 per family per year). There are also additional fees for school supplies, textbooks, uniforms, and activities such as taking exams, and these costs may deter parents from sending children, especially daughters, to school. This project was introduced in part to assist families of high-achieving girls to cover these costs.

Details of the intervention

The Girls’ Scholarship Program (GSP) was carried out by International Child Support (ICS) Africa, in two rural Kenyan districts, Busia and Teso. Out of a set of 127 schools, 64 were randomly invited to participate in a program which gave merit-based scholarships to 6th grade girls who scored in the top 15 percent on tests administered by the Kenyan government. For the next two years, winning girls received: (1) a grant of US$6.40 to cover school fees, paid to her school; (2)a grant of US$12.80 for school supplies paid directly to her family; and (3) public recognition at a school awards assembly held for students, parents, teachers and local government officials.

Academic achievement was captured in test scores, which are likely to be a good objective measure, and was not significantly affected by cheating. Exams in Kenya are administered by outside monitors, and district records from those monitors have no documentation of cheating.

Results and policy lessons

Implementation: Poor existing attitudes towards outside intervention and an educationally disadvantaged population meant that some schools in the Teso district were resistant to the program. Particularly, stronger indigenous religious beliefs and a tradition of suspicion of outsiders caused implementation difficulties, which may have reduced program effectiveness there.

Test Score Effects: The program raised test scores by 0.19 standard deviations for girls enrolled in schools eligible for the scholarship. These effects were strongest among students in Busia, where the program increased scores by 0.27 standard deviations. There are no effects found in Teso. Large positive test score gains were also found among Busia girls with low chances of winning the award, suggesting that there were positive externalities on learning. The average program effect for girls corresponds to an additional 0.2 grades worth of primary school learning, and these gains persisted one full year following the competition. There is also evidence of positive program externalities on the entire class; boys (who were ineligible for the awards) saw scores increase by 0.08 standard deviations on average.

Student Attendance: While the program impact on school participation is nearly zero among girls in the pooled Busia and Teso sample, the impact in Busia is positive at 3.2 percentage points. This corresponds to about a one-quarter reduction in school absenteeism.

Teacher Attendance: The program had a large impact on overall teacher attendance; in the pooled Busia and Teso sample there was a 4.8 percentage point increase in overall teacher attendance, and if these attendance gains were concentrated only among 6th grade teachers then this would imply a 7.6 percentage point increase in attendance. Once again, effects were larger in Busia—the impact on overall teacher attendance there was 7.0 percentage points, roughly halving overall teacher absenteeism. Teachers could potentially be gaming the system by diverting their effort towards students eligible for the program, but there is no difference in how often girls are called on in class relative to boys in the program versus comparison schools, indicating that program school teachers probably did not substantially divert attention to girls. This finding suggests that greater teaching effort was directed to the class as a whole.

Merit Scholarships and Inequality: The scholarship award winners did tend to come from relatively advantaged households, raising concerns about the distribution of benefits from this program. But in terms of student test score performance, the positive externalities affected all students, and were not concentrated amongst the most privileged.

Parental Involvement Effects: Anecdotal evidence from teacher interviews suggests greater parental monitoring occurred in Busia as a result of the program. One Busia teacher mentioned that parents began to “ask teachers to work hard so that [their daughters] can win more scholarships.” Another Busia teacher asserted that parents visited the school more frequently to check up on teachers, and to “encourage the pupils to put in more efforts.” When teachers were asked to rate local parental support for the program, 90 percent of Busia teachers claimed that parents were either “very” or “somewhat positive;” in Teso the analogous rate was only 58 percent. Thus, the greater improvements in both student and teacher attendance and performance in Busia as compared to Teso suggest that merit scholarships are most effective in the presence of local parental accountability and involvement, either formal or informal.

In J-PAL's comparative cost-effectiveness analyses, the scholarship led to a 1.38 standard deviation improvement in test scores and 0.15 additional years of education per $100 spent. For more information, see the full comparative cost-effectiveness analyses.