The Impact of Financial Incentives for Traditional Birth Attendants on Postnatal Care Use in Nigeria

- Health care providers

- Mothers and pregnant women

- Sexual and reproductive health

- Cash transfers

- Conditional cash transfers

Maternal and child mortality rates in Sub-Saharan Africa are among the highest in the world, with most deaths occurring in the first 48 hours after birth. Researchers evaluated whether giving traditional birth attendants (TBAs) cash incentives for maternal postnatal referrals can increase uptake of skilled maternal postnatal care. Cash rewards increased referrals made by TBAs by 182 percent and more than tripled the proportion of clients that attended postnatal care. However, clients of incentivized TBAs were still much less likely to receive postnatal care compared to mothers delivering in a health facility, suggesting that other potential barriers may prevent women from seeking and accessing care.

Policy issue

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest regional maternal and child mortality rates in the world, with 546 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and 1 in 12 children dying before the age of five. Furthermore, over 50 percent of maternal and newborn deaths occur in the early postnatal period (the first 48 hours after birth). The World Health Organization recommends postnatal care for all mothers and newborns within 24 hours of birth, regardless of where delivery occurs, since these visits provide an opportunity to check for and rapidly diagnose complications. However, only about half of women and newborns across Sub-Saharan Africa receive such care within 48 hours.

Previous research has examined the effects of financial incentives on maternal and child health-related behaviors, however these studies have largely focused on conditional cash transfers for the individual receiving health care. For example, cash transfers conditioned on precommitment to a delivery facility led to more effective birth planning among low-income pregnant women in Nairobi, Kenya and increased the likelihood that women delivered at higher-quality facilities.Alternatively, incentivizing health care providers, including those at the community level, to refer their clients to additional health services may increase uptake of health services and potentially prevent maternal and neonatal deaths. Can cash incentives for traditional birth attendants (TBAs) for referrals increase the use of early postnatal care?

Context of the evaluation

In 2013, 36 percent of births across Nigeria were delivered in a health facility, with a higher rate in Ebonyi state (60 percent)1 . Among women who give birth outside a health facility, 40 percent are assisted by TBAs. TBAs are community-based providers of pregnancy-related care who are not formally trained to provide early postnatal care.

In Nigeria, use of early postnatal care varies widely depending on the location of delivery. In 2013, 80 percent of mothers who delivered in health facilities received skilled postnatal care within two days of birth, while less than 20 percent of mothers who gave birth outside a health facility received such care. Given that they assist such a high proportion of deliveries, TBAs have the ability to influence the decisions made by mothers. However, they compete with skilled health workers for clients. Therefore, TBAs are often unlikely to refer their clients to facility-based health workers for postnatal care due to the risk of reputational harm and client loss in future pregnancies. This lack of incentives could prevent TBAs from encouraging their clients to seek out skilled early postnatal care.

Details of the intervention

Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to measure the impact of cash rewards for postnatal care referrals on postnatal care use in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. In August 2016, researchers recruited 207 TBAs from 128 wards that had at least one primary health care facility with a maternal health care provider offering maternal postnatal care. All TBAs were informed about the benefits of postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery and were encouraged to refer their clients for postnatal care within this window. Researchers then randomly assigned each TBA into one of two groups:

- Financial incentive: half of the TBAs (103) received NGN 600 (US$2 at the time of the evaluation) for every maternal client that received postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery. TBAs were encouraged to refer all maternal clients, not just those who experienced complications during birth. The incentive represented 25 percent of the average income earned per pregnancy.

- Comparison group: the remaining 104 TBAs received no incentive for referrals.

After two months, researchers surveyed TBAs’ clients at least three days after delivery. Clients were specifically asked about the use of maternal postnatal care, use of neonatal postnatal care, and their motivations for attending postnatal care. TBAs in the incentive group were then rewarded based on their clients’ reports of maternal early postnatal care attendance, rather than by official health facilities records due to unreliable quality of recordkeeping.

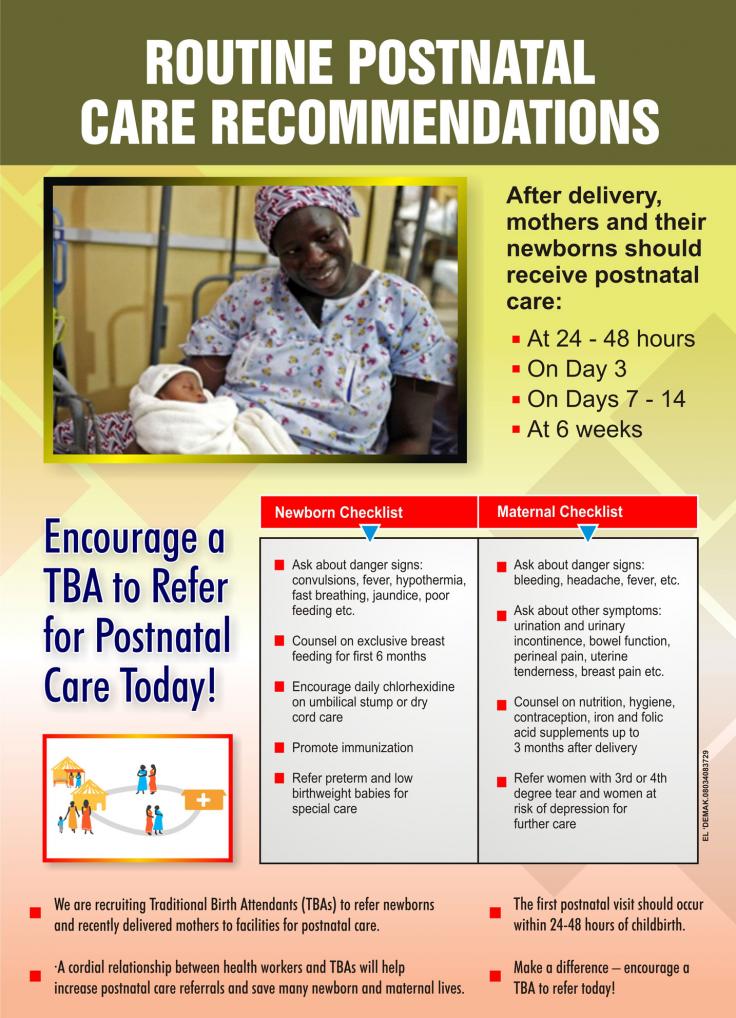

A poster used to recruit traditional birth attendants to refer newborns and recently delivered mothers to facilities for postnatal care. Click the image to enlarge.

Results and policy lessons

Cash incentives increased the number of referrals TBAs made by 182 percent, with incentivized TBAs making 0.31 more referrals compared to 0.17 referrals amongst non-incentivized TBAs. Incentives also increased the proportion of TBAs’ clients that attended maternal postnatal care by 15.4 percentage points, more than triple the proportion of clients in the comparison group (4.4 percent). The proportion of neonatal clients that attended postnatal care increased by 12.6 percentage points as well (approximately a three fold increase), despite TBAs not receiving incentives for use of neonatal health care. In 70 percent of cases, clients in both the cash incentive and comparison groups reported the advice of the TBA as the reason for attending early postnatal care.

These results are consistent with previous qualitative research in Nigeria suggesting that monetary incentives for performance may motivate TBAs to refer mothers to skilled providers for postnatal care. However, clients of TBAs in the intervention group were still much less likely to receive skilled postnatal care compared to mothers delivering in a health facility (16 percent compared to 79 percent of those who delivered in a facility). This suggests that other barriers such as the quality of healthcare or the cost of treatment may prevent women from following through on referrals. Future efforts to increase the use of skilled maternal health care in Nigeria may need to address these obstacles alongside incentives for TBA referrals.