Lesson #3 | What not-to-do: Wisdom from years of trials (and errors)

This blog is the final installation of a three-part series by J-PAL South Asia’s executive director Shobhini Mukerji reflecting on two decades of advancing evidence-based policymaking. Read Lesson #1: Don’t look for the Silver Bullet and Lesson #2: Don’t trade for short gains—play the long game.

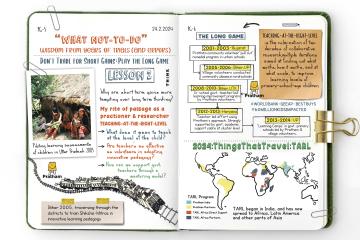

Galileo, like many scientific pioneers over the course of history, faced early skepticism. We all know how he was tried and convicted of heresy in 1642 when defenders of the traditional Ptolemaic worldview saw the developing heliocentric astronomy as a fundamental threat to their belief system. Perhaps it's not surprising then that early practitioners of randomised controlled trials, while not exactly facing Catholic inquisition, faced similar existential doubts.

Ethical concerns, external validity, resource- and cost-intensive, inability to capture multifaceted interventions and complexities of real-world decision making, long gestation periods… Working in this field for the last two decades, I am well versed with these (depending on context, sometimes well-founded) criticisms of randomised controlled trials. But isn’t it equally problematic to provide aid to unfounded programmes that don’t have a solid foundation or clear understanding of impact, potentially leading to wasted resources and missed opportunities?

This is my final lesson. Lesson #3: Putting the I in Impact—Don’t “underestimate” your potential

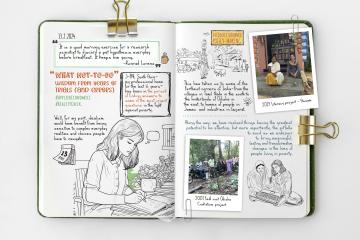

J-PAL, my home for the last sixteen years, has helped validate an invaluable lesson—one that my mother also instilled: “If you don’t stand up for something, you will fall for anything.” She was, of course, referring to my choice of boyfriends, but this caution has stood me in good stead in my work. We have been asked to make dashboards, set up project management units, join large consortiums with blurred roles and comparative advantage, and even build toilets and fortify rice. We have often been mistaken for consultants who will do their client’s bidding, crunch the numbers, and publish what is asked of them. There is nothing outrageous about this. But our work, our mission, our superpower, is far from this.

Our comparative advantage is our superpower: J-PAL’s mission is to conduct high-quality research and inform complex policy decisions with practical knowledge. We seek to be able to answer questions such as: How do you get children to master their three Rs? How do you get doctors to show up to work? How do you increase immunisation demand in the most cost-effective way? How do you enable farmers to effectively use digital extension tools to increase crop yield? How do you get communities to conserve their increasingly diminishing ecosystems? The questions are endless—and our premise to tackle these, some complex, some binary problems, is through a rigorous approach. We use a rigorous method and scientific evidence to answer questions critical to poverty alleviation, to understand what works, what doesn’t, and most importantly, why or why not, in the fight against poverty and climate change.

The key to testing is the randomised controlled trials (RCT) methodology borrowed from the medical field, applying the same rigour of testing a medicine to testing social policies. Some reveal surprises, like how microfinance may not be the transformative silver bullet to create entrepreneurs and lift millions out of poverty. Some validate common sense: if you give teachers a focused task (bringing children up to par with their grade level reading through targeted instruction and innovative pedagogy) and don’t overburden them with syllabus completion and administrative tasks, they can achieve a lot in a short time. Most importantly, we have seen that when we have the right set of ingredients to knead the dough, magic happens—in other words, we can achieve real, meaningful impacts for people in need. Our goal is to ultimately improve decision-making based on evidence.

And the key to scaling effectively, based on evidence, is the accompanying generalisability framework in establishing external validity. Can we take an impactful livelihoods programme tested in West Bengal through an NGO to Bihar in partnership with the government? Can we integrate a gender attitudes curriculum resulting in changed attitudes for adolescent boys and girls in Haryana’s government schools to Odisha? And can a learning program tested in India be taken to Africa? Our experiences with partners have shown that yes, we can scale effectively. In my last blog, Play the Long Game, I talked about Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL), the culmination of two decades of collaborative research, multiple iterations aimed at finding out what works, how it works, and at what scale, to improve learning levels of primary-school-age children.

Why do I believe in RCT’s potential to solve complex problems? Why do I not underestimate its application to solutioning even multi-dimensional problems such as poverty? It lies in embracing the scientific approach. Break down the problem statement logically, have a set of questions and concrete hypotheses, test them rigorously. Once the programme or proposed solution passes the rigour of an RCT evaluation, the next step is to understand if this can be replicated or scaled if found to be impactful. If the conditions that make a programme work in one place hold elsewhere, then such poverty alleviation programmes can get traction more widely. Different types of evidence can be used to assess the different steps in the generalizability framework. And we have applied this principle to many fields, from learning, to political participation, to climate change, to using nudges and incentives to improve service take-up and so on.

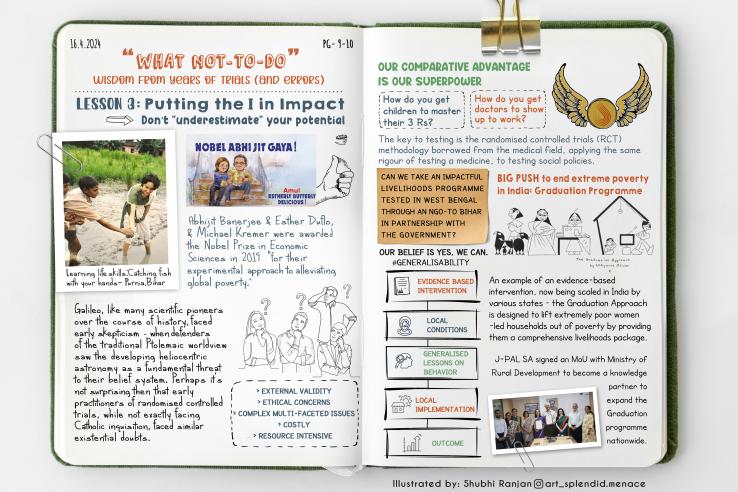

An evidence-based scale-up: The example of the Graduation Approach

In 2015, armed with evidence of the effectiveness of a transformative livelihoods programme for low-income women tested in Murshidabad district of West Bengal, our India-based policy associates knocked on the doors of many governments. Their motivation was to share the research results and help think through how the programme could be adapted in other states with J-PAL as a trusted evidence partner. Four state governments responded and invited us and our implementation partner to conduct some pilots (proof of concept) to test whether the programme indeed works in their state.

This was a programme, now known internationally as the Graduation Approach, that was initially conceived by BRAC in Bangladesh and evaluated in seven countries simultaneously—including in West Bengal by the NGO Bandhan Konnagar in 2007. The programme followed a series of steps involving transfer of a productive asset (usually a goat or poultry, shop, or sewing machine) to a woman-headed, extremely low-income household which, at the time of the transfer, could not save even 5 rupees per week or eat two meals a day. This was coupled with training to manage the asset, regular coaching, access to savings, and cash transfer. The RCT found that the programme led to large and long-lasting positive impacts on the standard of living, income, and consumption as well as intergenerational impacts on mobility and growth, even up to ten years after the formal support ended.

At the end of two years of the pilot in Bhagalpur district, the Bihar government was convinced it was worth taking forward. This involved adeptly securing financial and personnel commitments by the bureaucracy and getting political buy-in. Our priors based on previous experience were endorsed as well—that an NGO-led programme as complex as this could indeed be integrated within a government system. Based on evidence of the success of the programme, the government has since committed USD 250 million toward eradicating poverty in Bihar through the Graduation model.

The partnership that has followed since 2018 with Jeevika (National Rural Livelihoods Mission) and the Rural Development Department in Bihar has been one of close collaboration, transparency and top-to-bottom alignment between Jeevika, the Department, Bandhan-Konnagar, and J-PAL South Asia teams. A 5,000-strong team of “master resource persons,” who will serve as programme staff, have been inducted by the government to take this programme forward on the ground. Through a dedicated project management unit and a data architecture system, Jeevika has been using feedback from the field for strategic and operational decision-making. J-PAL South Asia and Bandhan-Konnagar have supported Jeevika in building internal capacity, visualising and using the daily information aggregated at multiple levels as the program scales. J-PAL South Asia’s on-the-ground teams continue to engage in process monitoring (field-based surveys) to capture changes in consumption, income, and related indicators on health and education outcomes.

This programme is also transforming the lives of the women at a granular level. Researchers found that the Graduation Approach was an important pathway for economic inclusion even amid the Covid-19 crisis: investing in the Graduation Approach in Bihar before the pandemic enabled the government to quickly extend financial and mentoring support to ultra-poor households once the crisis began. While the lockdown affected the women’s ability to run and develop their enterprises, they had access to a source of income even as other sources such as casual labour became untenable. These women and their families were non-existent in the government’s records before this programme began.

On March 15, 2024, the Union Ministry of Rural Development signed an MoU with J-PAL South Asia to promote inclusive development and empower rural low-income women to become self-sufficient. Building on nearly two decades of experience with BRAC and Bandhan-Konnagar, this partnership supports the Government of India’s Samaveshi Vikas (Inclusive Growth) campaign. J-PAL South Asia continues to convene donors, non-profits, and governments to share insights and secure funding to expand this work.

If we had underestimated our beliefs in the potential of RCTs to generate real impacts for real people, we would have adapted to the prevailing norms in impact assessment and not catalyzed a new space for evidence-informed decision-making.

The field of RCTs has gained wider applicability and informed the practice of research compared to when I started working in this field more than two decades ago. The early pioneers of randomised controlled trials in the social sciences didn’t settle for less and nor must we. The consulting approach is not a substitute for serious research. It can be tempting to settle for a simple, impractical dashboard to keep a client satisfied, make a “systems change plan” based on the limited information available, or power up the collaborating department’s unit with a fleet of external professionals to do the job—in other words, “band-aid” solutions to the problem at hand. But in the end, are we really creating the true systems change impact that is needed to benefit people on the ground? Are we questioning, engaging intellectually, and not just parroting jargon for the sake of acceptability? Are we contributing in a long-term holistic way to considering all the incentives of the stakeholders involved towards the same goal? Not your goals or mine, but ultimately the goals of those who will be impacted by the change.

We and our partners must together be committed to long-term change instead of seeking a silver bullet, never underestimating the potential of rigorous research, learning from failures, and building the capacity of our teams and partners as we walk the hard path of rigorous impact at scale.

In case you missed it, check out my earlier posts: Lesson #1: Don’t look for the Silver Bullet and Lesson #2: Don’t trade for short gains—Play the long game.

I hope you have enjoyed reading this blog series with me as much as I have enjoyed writing them. Please feel free to contact me at [email protected] with your comments and suggestions.