Deworming to increase school attendance

School-based deworming is a low-cost intervention that takes advantage of existing school infrastructure and trains teachers to administer deworming treatment—safe tablets—to all primary school students on dedicated “deworming days,” once or twice per school-year. Because the tablets are inexpensive relative to diagnosis, which requires analysis of a stool sample in a laboratory, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends periodic mass treatments in areas where more than 20 percent of children have worm infections. Research by J-PAL affiliated professors Michael Kremer (Harvard University) and Edward Miguel (University of California, Berkeley) has shown that school-based deworming of students improved health and school attendance in Kenya. Subsequent research has shown that deworming also increased the percentage of girls who passed a primary school exam and attended secondary school, and increased hours worked for men who were in treatment schools as children. Research conducted by J-PAL affiliates has led to the launching of school-based deworming campaigns in Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, and Vietnam.

The Problem

Worm infections affect student health and school attendance.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 835 million children are in need of treatment for intestinal worms, which are transmitted through contact with water or soil contaminated with fecal matter.1 Worm infections can reduce the absorption of nutrients in the body, leading to anemia and malnutrition, and weaken the body’s immunological response to other infections such as malaria. Infected children may become too sick to attend school or too tired to concentrate in class. Because intestinal worms are most prevalent in low-income countries where diagnosis is relatively costly, the WHO recommends periodic mass administration of anthelmintic drugs to groups of people in worm endemic areas. Oral deworming drugs are extremely effective with a single dose, at a cost of a few cents per tablet, and are safe for those without worm infections. Periodic administration every 6–12 months addresses reinfection and the health problems associated with high worm load.

Intestinal worms are pervasive in the developing world and can have devastating effects. But there is growing awareness about how easy and inexpensive it is to treat worms, as well as surprising longer-term socioeconomic benefits. Research shows deworming to be extremely cost-effective: you get a lot of bang for your buck.

— The New York Times, Fixes blog. April 2012

The Research

School-based deworming improved school attendance in the short term, productivity in the long term, and benefited neighbors and siblings.

From 1998 to 2001, Kremer and Miguel evaluated the Primary School Deworming Project in Kenya. This program provided deworming tablets for soil-transmitted intestinal worms and schistosomiasis, as well as instruction on how to avoid worm infections, to children in 75 primary schools in rural Busia, Kenya.

At a cost of less than US$0.60 per child per year, school-based deworming reduced serious worm infections by 61 percent and reduced school absenteeism by 25 percent. There were positive spillovers in the form of reduced disease transmission among untreated children within treatment schools and for children who attended schools within three kilometers of treatment schools. Unlike previous studies, researchers quantified these spillover effects and showed that previous studies had underestimated the benefits of deworming.

Evidence from recent rigorous studies in three different contexts suggests substantial impacts of childhood deworming on school participation, cognition and test scores, and adult labor market outcomes.

— Vox CEPR’s Policy Portal, August 2015

A long-term follow-up found that deworming also improved school performance and future earnings. Deworming led to large academic gains for girls, increasing the rate at which girls passed the secondary school entrance exam by 9.6 percentage points over the comparison group mean of 41 percent. Men who were dewormed as children worked 3.5 more hours per week, spent more time in entrepreneurial activities, and were more likely to work in higher-wage manufacturing jobs than their untreated peers.

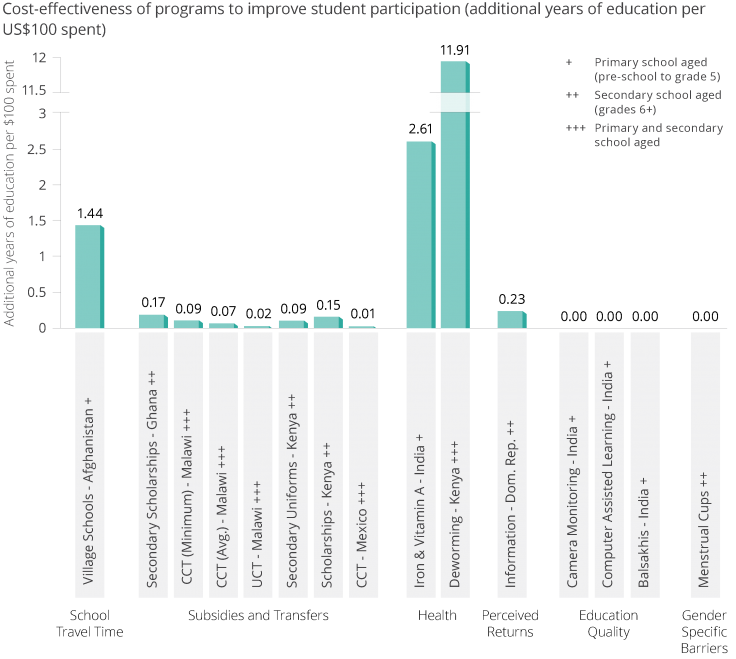

We estimate that school-based deworming adds 11.9 years of education per US$100 spent. Among interventions that have been rigorously tested by randomized evaluations, school-based deworming is one of the most cost-effective means of increasing school attendance.

For more information about this project, see the evaluation summary.

From Research to Action

Based on research conducted by J-PAL affiliates, school-based deworming campaigns have been adapted and scaled in Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, and Vietnam.

Following a presentation of the evidence on the impact of school-based deworming by Kremer and Esther Duflo (MIT) at the 2007 World Economic Forum, Deworm the World was launched as an independent organization to coordinate technical assistance and advocacy efforts for sustainable, large-scale school-based deworming programs.

In 2009, Kenya’s then-Prime Minister, Raila Odinga, announced the start of the National School-Based Deworming Programme at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting. The program is a collaboration between the Kenyan ministries of Education, Science, and Technology, and Health. Kenya’s National School-Based Deworming program is now in its seventh year since being relaunched in 2011, consistently treating over six million children across the country. Even during the Covid-19 pandemic, the program reached 2.8 million children two months after schools reopened.

In 2010, J-PAL hosted a conference with the government of the Indian state of Bihar to share evidence on school-based deworming and other promising programs. Following these discussions, the Bihar government, with support from Deworm the World, launched a state-wide deworming campaign, reaching 17 million children in 2011. Other large-scale deworming programs followed in Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, and Rajasthan in subsequent years and, in February 2015, the Government of India launched a national deworming program. This program now reaches 260 million schoolchildren each year. When schools were closed during the Covid-19 pandemic, the government adapted the program to be delivered by frontline health workers.

The Deworm the World Initiative is now a program of the nonprofit organization Evidence Action, which builds long-term partnerships and provides technical assistance to help governments including in Kenya and India launch, monitor, and sustain school-based deworming programs. Incorporating best practices from India and Kenya, the Government of Ethiopia also launched a national school-based deworming program in 2015 with support from the Deworm the World Initiative and the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. In 2017, the program treated nearly 15 million children.

Between 2014 and 2020, the Deworm the World Initiative partnered with the Government of Vietnam to strengthen the delivery, reach, and monitoring of its school-based deworming program. Starting in 2016, the Deworm the World Initiative began supporting treatment in Nigeria, where deworming reached 4.8 million children across four states in 2021.

In 2016, a national-level survey was conducted in Pakistan to map worm prevalence and intensity. The survey indicated the need for annual deworming treatment for an estimated 17 million school-age children in 45 at-risk districts across the country. With support from Evidence Action and partner Interactive Research & Development, the Federal Ministry of Planning, Development and Special Initiatives incorporated the deworming program into the Government of Pakistan’s five-year plan in 2019. In 2021, the government launched its first national deworming awareness campaign in order to achieve widespread national recognition for the Pakistan Deworming Initiative. That year, 8.3 million children in Pakistan received deworming treatment.

Beyond these national-level strategies, the World Health Organization has also cited this research in informing the expansion of their deworming program.

The study by Michael and colleagues essentially confirmed the benefits of deworming, advocated for and facilitated the expansion of the programme that in 2018 alone treated over 450 million schoolchildren worldwide.

— Antonio Montresor, head of the control programme for soil-transmitted helminthiases, WHO 2019

This case study was originally published in October 2018 and updated in September 2022 to include recent program developments, particularly adaptations to the Covid-19 pandemic.

References

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2017. “Roll Call: Getting Children into School.” J-PAL Policy Bulletin. Last modified August 2017. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/publication/roll-call-getting-children-school.

Bobonis, Gustavo, Edward Miguel, and Charu Puri-Sharma. 2006. "Anemia and School Participation." The Journal of Human Resources 41 (4): 692-721. https:///doi.org/10.3368/jhr.XLI.4.692.

Miguel, Edward, and Michael Kremer. 2004. "Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities." Econometrica 72 (1): 159-217. https:///doi.org/10.3368/jhr.XLI.4.692.

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2020. "Deworming to increase school attendance." J-PAL Evidence to Policy Case Study. Last modified September 2022.

World Health Organization. 2018. “Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections.” WHO Fact Sheets, 20 February 2018.