Administrative steps for launching a randomized evaluation in the United States

Summary

This checklist provides guidance on the logistical and administrative steps that are necessary to launch a randomized evaluation that adheres to legal regulations, follows transparency guidelines required by many academic journals, and complies with security procedures required by regulatory or ethical standards. Many of these steps require advanced planning at the beginning of the research process. The order of completion may vary by project; this list is not necessarily chronological, and many steps are interdependent.

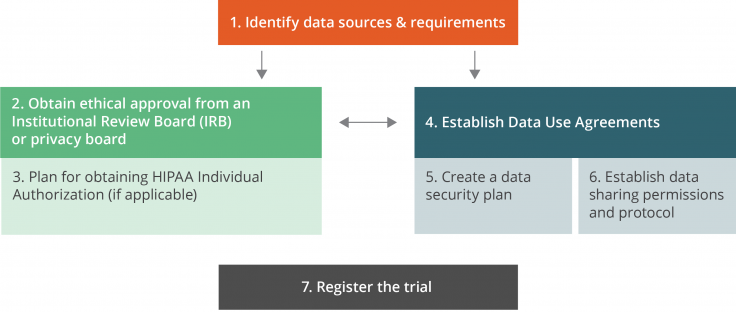

Main relationships between the administrative steps

1. Identify data sources and requirements

If the data necessary for an evaluation are collected in administrative data, using such data may lower data acquisition costs and lower the risk of certain biases relative to primary data. However, researchers must understand the quality, limitations, diversity, equity and inclusion implications, and regulations governing the use of that data. Researchers should also be conscientious of whether individuals in the evaluation will be captured in the data. Researchers will likely need to apply for permission to use the data (see Step 4 for more details) and identify a viable strategy for matching the data to the study sample. The process of getting permission to use and match data can be time consuming, and there may be time lags between when an event occurs and when it is reflected in the data, so researchers should adjust the timeline of the evaluation launch accordingly. The subject or source of administrative data typically determines which regulations apply; education data may be subject to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), health data may be subject to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and data from certain U.S. states are subject to state law.

Planning for primary data collection involves developing instruments for collecting the data (e.g., surveys, biomarkers, direct observation, spatial geography applications, etc.), validating the instruments through field-testing, training data collectors, and providing ongoing oversight and monitoring to ensure data is being collected consistently and reliably.

The level of identification of administrative data, as well as the sensitivity and types of information obtained through primary data collection, have implications for the requirements for ethics approvals, data use agreements, informed consent, and data security. Understanding how sensitive the required data is will enable researchers to better approximate the length and rigor of the approval processes.

For more information, see J-PAL North America’s Catalog of Administrative Data Sets as well as “Using administrative data for randomized evaluations,” in particular the “Potential bias” sub-section under “Why use administrative data?”

2. Obtain ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Privacy Board

Research involving humans, or individual-level data about living humans, is likely1 subject to review by an Institutional Review Board (IRB), even if no direct interaction between subjects and researchers is involved. Their review may determine that a research project is 1) not human subjects research and thus not subject to any further review, 2) exempt from ongoing review, 3) eligible for expedited review by an IRB administrator, or 4) subject to review by a full IRB. These determinations are made by the IRB, not by the research team, based on the study’s potential impact on the health and well-being of study participants.

If multiple institutions with IRBs are involved in the research (e.g., when co-investigators are affiliated with different universities, or an implementing partner has a separate IRB), researchers will either need to get approval from each IRB individually, or apply for an IRB Authorization Agreement (IAA), which allows one institution to rely on another for IRB review, approval, and continuing oversight. This mechanism is recommended for research projects that involve multiple intuitions with IRBs, as it greatly expedites the IRB review process when one IRB is designated as the primary reviewer.

The IRB will likely require all investigators and study staff who will have direct interaction with study participants (e.g., to obtain consent or conduct study enrollment) or access to identifiable information to complete a human research training course such as the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) Program.

Applying for IRB approval requires describing the research protocol and intervention in a way that enables the IRB to conduct a substantive review. In addition, any materials used to collect data (including any questionnaires or surveys used, or data use agreements used to acquire administrative data) or recruit participants (including advertising materials) must be reviewed and approved.

After approval, protocols that have not been exempt are subject to ongoing review. This includes reporting of any new staff, changes to study procedures, changes to surveys used, and reporting of adverse events. Contact the IRB of record with any questions regarding what should be reported or included in annual reviews.

For more information, see the "Compliance" section and the "Consent and authorization" appendix of “Using administrative data for randomized evaluations.”

Timeline

Most IRBs require at least one month to complete their review, and many advise allowing for a longer review period. Harvard University, for example, suggests submitting applications at least two months before the anticipated start date of research.

Additional considerations

IRBs often require researchers to furnish signed data use agreements (DUAs) before fully approving a study protocol, and data providers often require IRB approval before executing a DUA. Both processes can involve lengthy review periods, and changes made by one entity must be reviewed and approved by the other. Researchers can actively communicate with each entity to resolve this. For example, an IRB may be willing to provide provisional approval for a research study, with final approval contingent on an executed DUA. See Step 4, Establish Data Use Agreements, for more information on DUAs.

3. Plan for obtaining HIPAA individual authorization

A signed record of an individual’s authorization may be required in order to obtain data from certain healthcare or health-related entities. This includes, but is not limited to, data containing personally identifiable information that are considered Protected Health Information (PHI) under HIPAA. HIPAA regulations impose criminal and/or civil penalties on individuals who use or share data inappropriately. These penalties apply to data providers and may also apply to researchers who obtain such data; therefore, data providers take many precautions before releasing data to researchers.

Certain requirements of authorization may be waived or altered at the discretion of the IRB with adequate justification from the researcher. In many cases, the authorization and informed consent process may be combined.

For more information, see the "Compliance" section and the "Consent and authorization" appendix of “Using administrative data for randomized evaluations.” Individual authorization has many parallels with the informed consent process required by IRBs; guidance on developing a consent process can be found in the “Define intake and consent process” section of this toolkit.

Additional considerations

While certain elements of authorization are requirements, slight tweaks in the written language or delivery style of the staff member guiding potential research subjects through the authorization process may impact take-up rates and compliance. Consider careful training of any individuals who will be guiding potential subjects through the authorization process, and consider piloting different methods of explaining the authorization. Guidance on training can be found in the “Who will conduct enrollment?” sub-section of the “Define intake and consent process” section of this toolkit.

4. Establish data use agreements

A data use agreement (DUA), documenting the terms under which a provider shares data and a researcher uses data, is often required in order to access data from another institution. DUAs, which typically must be approved by legal counsel at the researcher’s home institution, often contain restrictions on data use, security requirements, and publication requirements that can significantly impact the underlying research or academic freedom.

Many universities have a standard template that includes terms and conditions that are acceptable to the university and were created with researchers’ needs in mind. Using a pre-vetted template may simplify the review process at the institution that created the template.

For more information, including elements of particular importance in reviewing DUAs and tips for negotiating these agreements, see the “When necessary, establish a legal research agreement” and “Data use agreements” sections of this toolkit.

Timeline

In a 2015 analysis of data acquisition efforts with 42 data agencies, MDRC found that it typically takes 7 to 18 months from initial contact with a data provider to the completion of a legal agreement.2 Much of this time is spent in a tandem process of obtaining both IRB and legal approval for a data request. IRBs often require researchers to furnish signed DUAs before approving a study protocol, and data providers often require IRB approval before signing a DUA. Both processes can involve lengthy review periods, and changes made by one entity must be reviewed and approved by the other.

5. Create a data security plan

Any data set containing personally identifiable information – especially if it also contains potentially sensitive information – should be safeguarded. IRBs, data providers (e.g., the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services), and some funders (e.g., the National Institutes of Health) require descriptions of data security procedures. This includes a description of user access controls, data sharing policies, encryption or password policies, and potential for re-identification.

Ensuring proper data storage is an important component of data security. Plan to prevent loss of essential data, including raw data, treatment assignment lists, and crosswalks between de-identified study IDs and personally identifiable information. These data should be backed up regularly in at least two separate, secure locations.

Some projects may require plans for new data storage locations, such as an institutionally hosted server, an offline-only computer stored in a secure location, or simply a folder on a cloud-based storage provider (e.g., Box, Dropbox, Google Drive). Choice of storage location depends on data security requirements and data use agreement provisions.

For more information, see "Data security procedures for researchers."

6. Establish data sharing permissions and protocol

J-PAL and a number of grant-making institutions, including the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, have adopted data-sharing policies for research that they fund. Many top academic journals require data and replication code sharing as a condition of publication (e.g., American Economic Review, Econometrica, and Science.)

Developing and storing data sets and code with publication in mind will decrease the burden of preparing data later in the research process.

Permission from data providers – both individuals and data providers such as agencies or companies – may be necessary to publish even de-identified data. Data use agreements may need to include provisions allowing the publication of data and may influence the level of dis-aggregation allowed. Review boards may require that informed consent and/or HIPAA authorization processes include any plans for the publication of data, as well.

Even when data cannot be shared because of its sensitivity or because of data use agreements, it is still possible to share replication code, metadata, codebooks, and data access and matching procedures to allow other researchers to understand and possibly replicate your work. Making every effort to share data is a best practice for making social science research transparent and reproducible.

For more information, see J-PAL’s resources on transparency and reproducibility.

7. Register the trial

Registration on clinicaltrials.gov is required by the FDA for many medical, clinical, or health related trials. Registration and reporting of results on clinicaltrials.gov is required by NIH for all NIH-funded clinical trials. NIH defines clinical trials broadly to include evaluations of interventions not regulated by the FDA, including behavioral interventions like those investigated in the social sciences. Medical journals may require registration on clinicaltrials.gov as a condition of publication even if FDA or NIH regulations do not apply.

Registration on other sites such as the American Economics Association’s RCT Registry (which is supported by J-PAL) or OSF may be required by project funders, including J-PAL. Registering trials is a method of ensuring transparency. Trial registries provide a source of results for meta-analysis and may serve as a resource for locating available survey instruments and data.

Trial registration must take place prior to launch of the intervention being studied.

Last updated September 2021.

These resources are a collaborative effort. If you notice a bug or have a suggestion for additional content, please fill out this form.

We are grateful to Amy Finkelstein and Pauline Shoemaker for their insight and advice. This work was made possible by support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Arnold Ventures.

Additional Resources

Catalog of administrative data sets | https://www.povertyactionlab.org/admindatacatalog

Measurement and data collection | https://www.povertyactionlab.org/research-resources/measurement-and-data-collection

Transparency & reproducibility | https://www.povertyactionlab.org/research-resources/transparency-and-reproducibility

J-PAL North America’s Catalog of Administrative Data Sets catalogs a number of key U.S. data sets and documents procedures on how to access data based on information provided by the originating agencies.

"Using administrative data for randomized evaluations," developed by J-PAL North America, provides general, practical guidance on how to identify administrative data sources, assess their quality and contents, understand relevant requirements, and obtain and use nonpublic administrative data for a randomized evaluation.

“The Lessons of Administrative Data” highlights examples of high-profile studies made possible by administrative data.

Resources on primary data collection can be found on the J-PAL website.

Information about integrated data systems can be found on the Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy website.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Center for Health Statistics have a toolkit on how to collect, use, protect, and share health data responsibly.

Researchers at Harvard University are working to develop tools to help researchers understand what regulations apply to data based on an interactive questionnaire. Institutional Review Boards, data librarians, and compliance offices may also be useful to determine which regulations apply.

IRBs review protocols based on the requirements of the Common Rule (45 CFR 46.116). Referencing the rules and writing protocols and applications with the rules in mind may help improve communication between the research team and the IRB and increase the chances of a successful application.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT’s) Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) provides examples of what various types of application forms might look like and includes instructions.

COUHES also has guidelines for various procedures in the IRB review process.

Harvard University’s Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (CUHS) provides further examples of application forms.

The University of Colorado has several guidance documents relating to all elements of the IRB process.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services presents decision charts for understanding IRB requirements.

The National Institutes of Health has sample protocols, including one designed for behavioral and social science researchers, available in the NIH e-protocol writing tool.

45 CFR 164.502 – Uses and disclosures of protected health information (original text).

45 CFR 164.508 – Uses and disclosures for which an authorization is required (original text). HIPAA regulations pertaining to authorizations for the release of health information, and requirements of the authorization.

NIH guidance on complying with HIPAA, including Authorization for research and waivers of Authorizations.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ guide to understanding the HIPAA Privacy Rule’s relationship to researchincludes descriptions of the specific requirements of an authorization for research.

Many universities have a standard template that includes terms and conditions that are acceptable to the university and were created with researchers’ needs in mind. Using a pre-vetted template may simplify the review process at the institution that created the template.

- MIT has sample data use and nondisclosure agreements here.

Many research universities provide support and guidance for data security through their IT departments and through dedicated IT staff in their academic departments. Researchers should consult with their home institution’s IT staff when setting up data security measures, as the IT department may have recommendations and support for specific security software.

Cloud-based storage providers offer a range of options for data backups and may offer additional packages to back up data for longer periods of time to protect against the unintentional erasure of data. Institutional servers may have data backup plans, with device-level backup plans also available. Backing up data to an external hard drive (stored in a separate location from daily computers) is an option for low-connectivity environments.

For researchers at MIT, Dr. Micah Altman, Director of Research at MIT Libraries, regularly presents talks on Managing Confidential Data.

MIT’s Information Systems & Technology Department provides resources on (require MIT login):

- Protecting data

- Secure Shell File Transfer Protocol: SecureFX

- Encryption (including software recommendations) and whole-disk encryption

- Removing sensitive data

Harvard University’s Research Data Security Policy (HRDSP) is an excellent resource for security level classification and security requirement examples.

J-PAL hosts resources and links to additional information about transparency and reproducibility.

The Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences (BITSS) is an excellent source of information on reproducibility and data publication. They frequently host in-person educational sessions. Their Manual of Best Practices in Transparency in Social Science Research offers suggestions on how to write replicable analysis code from the beginning.

Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) hosts resources on research transparency. For IPA-affiliated researchers, they offer additional support for data curation and code checking. Their manual of Best Practices for Data and Code Management covers the principles of organizing and documenting materials at all steps of the project lifecycle with the goal of making research reproducible.