Digital payments in sub-Saharan Africa: Trends over the past decade

Between 2008 and 2010, poverty in Kenya was reduced by two percent due to better access to mobile money services. This impact translates to 194,000 Kenyan households no longer living below the poverty line, with the largest reductions found in female-headed households. This is one of several benefits of digital payments.

Mobile money reduces the costs of delivering money from one location to another. Instead of physically transporting funds, mobile money funds are transferred digitally between users’ mobile phones and only requires users to have a phone number to participate in the transfer. This kind of payment platform is particularly valuable for individuals who aren’t well-connected to formal financial systems and don’t have access to a bank account. The digital mode of transfer means the money can be transmitted more quickly, conveniently, and cheaply across large geographical distances. For example, using figures from 2008, it is much cheaper to send a transaction two hundred kilometres (the average distance of a transaction) using mobile money with a fee of US$0.35, compared with physically transporting the cash and being charged a bus fare of US$5 to travel the same distance.

An additional benefit of digital payments includes improved security. Indeed, mobile money can be particularly beneficial in countries where the opportunity cost of holding cash may be high, such as cities with a high-crime rate. The ability to handle money in digital form compared with physical cash could mean one would be less of a target for theft. For example, taxi drivers may prefer to store their earnings digitally, especially if there is a likelihood of being hijacked in the neighbourhoods where they work.

However, mobile money only functions with the appropriate infrastructure in place. Although access to mobile phone technology is growing, it isn’t universal, and lack of access to a mobile phone may limit the ability of individuals to benefit from the digital payment system. In addition, there may be a host of consumer protection concerns that could arise if privacy regulations aren’t well designed or customers aren’t aware of their rights.

To better understand the potential pathways and scale of potential impact, we summarise the findings on the expansion of digital payments, such as mobile money, in sub-Saharan Africa over the past ten years using the recent Global Findex Database report (2022). We discuss the key trends of ownership and usage of digital payments and highlight how the barriers to the adoption of digital payments have evolved over this period.

Expansion in ownership: Mobile money drives the increase in account ownership in sub-Saharan Africa, where 33 percent of adults now have a mobile money account.

Over the past decade, we have seen considerable growth in ownership of accounts at a bank or regulated institution such as a credit union, microfinance institution, or mobile money service provider. In Sub-Saharan Africa, large increases in account ownership are largely driven by growth in mobile money account ownership. Approximately one-third of adults in sub-Saharan Africa now have a mobile money account, compared with 10 percent of adults globally, which emphasises the disproportionate share of mobile money account owners residing in sub-Saharan Africa. Benin, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Malawi, the Republic of Togo, and Zambia experienced particularly high growth rates—increases larger than 10 percent—in mobile money ownership between 2014 and 2021.

Expansion in use: In sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money generated an increase in remittances and displaced less formal channels of saving with formal mechanisms.

Account ownership is only the first step in ensuring financial inclusion—but considering if and how accounts are used by consumers is also important to understanding how financial inclusion may translate into improved livelihoods. Key levers for this are remittances and savings.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 53 percent of adults sent or received domestic remittances in 2021. Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Senegal, and Uganda all had a higher concentration of remittances with approximately two-thirds of the adult population sending or receiving such payments. When it comes to remittances, researchers have found that households with access to mobile money services are better able to cope with negative life events when they occur. When a household experiences a shock, the households with access to mobile money are more likely to receive a remittance from their personal networks such as family and friends, receive a larger total amount of money, and receive it from a more diverse set of people. The increase in remittances distributes the risk that is associated with that negative life event over a larger network of people. Mobile technology allows this larger network to share resources safely, more cheaply, quickly and potentially to locations where access may not have been possible without the technology.

Savings offer households a buffer that enables them to invest in or respond to unexpected setbacks. For this savings channel in sub-Saharan Africa, we see that formal savings increased, while informal savings decreased, between 2017 and 2021. Approximately one-quarter of adults in sub-Saharan Africa indicated they saved formally through a mobile money account or financial institution in 2021, compared with 15 percent of adults in 2017. However, the data show mobile money accounts displaced less formal channels of saving. While the share of adults who saved—both formally and informally—in sub-Saharan Africa remained unchanged between 2017 and 2021, saving using mobile money specifically expanded during this period. Countries where mobile money accounts are more universal, like Ghana, Kenya, Senegal and Uganda, saw higher rates of savers using mobile money as a platform to save.

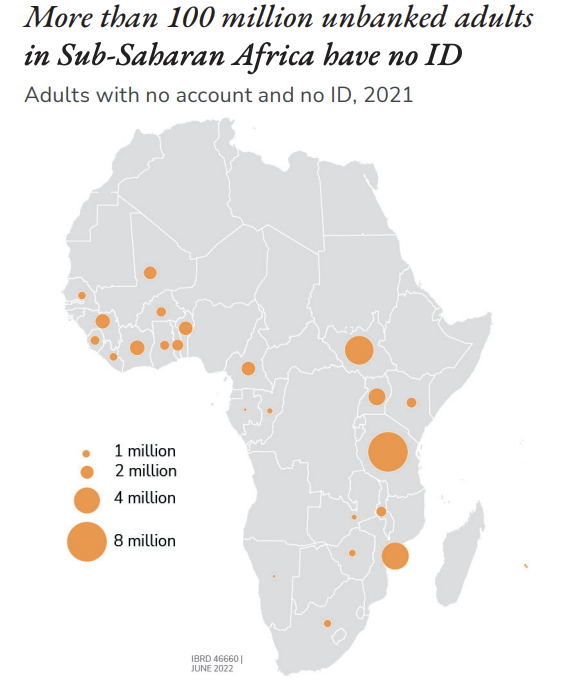

Barriers to ownership and use: In sub-Saharan Africa, 105 million adults are both unbanked and do not own an ID.

While easy to use and set-up, mobile money accounts still require users to provide an official identity document. The necessary documentation to open a formal bank account could be a critical impediment to account ownership in certain countries. In Liberia, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Sudan, and Tanzania, more than 40 percent of unbanked adults cite a lack of documentation as a reason for not owning a financial institution account. The issue is widespread: in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Bank’s Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative, 105 million adults (16 percent of all adults) are both unbanked and do not own an ID.

Women in sub-Saharan Africa are more vulnerable compared with men (by 5 percentage points) to fall in the category of being unbanked and without an ID. The gender gap in account ownership likely has many reverberating effects on women given the evidence that transferring funds through direct deposits to women’s accounts or mobile wallets has been shown to give women more control over the use of financial resources and improved economic empowerment. Particularly large gender gaps, of being both unbanked and without an ID, are seen in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Liberia.

Over the last 10 years, there has been an expansion of bank (or regulated institution) account ownership and usage in sub-Saharan Africa. This has been driven largely by the expansion of mobile money, with individuals using mobile money to safely save and send money, often through remittances. Nevertheless, barriers to access this innovative technology persist: Lack of documentation is cited as one of the reasons for not having a bank account and, in sub-Saharan Africa, 105 million adults are both unbanked and do not own an ID. We at DigiFI Africa are interested in funding new research projects on the impacts of new ID systems on a host of welfare issues, including financial inclusion. For more information on our key questions of interest, please see our framing paper.

Extra resource: DigiFI Africa recently launched a dashboard on the state of digital payments and digital IDs in Sub-Saharan Africa

The dashboard serves as a go-to reference for researchers seeking a broad overview of the current rollout of national IDs and digital payments in sub-Saharan Africa. The dashboard was constructed and edited by Thokozile Malaza (J-PAL Africa), Nidhi Parekh (J-PAL Africa) and David Boroto (J-PAL Africa). Find the dashboard.

All figures and numbers come from the most recent Findex report: Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Saniya Ansar. 2022. Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO