Improving the Transparency and Delivery of a Subsidized Rice Program in Indonesia

- Transparency and accountability

- Corruption and Leakages

- Information

Governments around the world face the challenge of ensuring that the rules governing social assistance programs for the poor are implemented as intended. Within Indonesia’s national subsidized rice program, researchers tested two interventions designed to improve service delivery and reduce program leakage: increasing program transparency by sending households official identification cards with information about the benefits they were eligible to receive, and providing villages with the option to privatize rice distribution. Providing information about benefits on official ID cards substantially increased the total benefits eligible households received and led to a large reduction in leakage. Privatizing rice distribution also improved program performance and reduced the price households paid for rice.

Policy issue

Social assistance programs like cash transfers and food subsidies are one of the primary channels through which people interact with their government, but service delivery presents a complex challenge. Without a clear understanding of how a government program is supposed to work, people are less equipped to expect and demand better performance.

Transparency and accountability between a government and its citizens are critical for effective public service delivery. In theory, providing people with information about the government benefits that they are entitled to can help them advocate for better service delivery and hold government officials accountable. It is not clear, however, whether this occurs in practice.

One potential way to ensure social programs reach their intended beneficiaries is to provide people with information the benefits that they are eligible to receive.

Another possible way to improve program delivery is to privatize implementation, as governments can often provide stronger performance incentives to private contractors than to their own employees. However, the impact of privatization is unclear because stronger incentives could also push contractors to lower program quality to cut costs.

Context of the evaluation

Rice comprises a large share of the household budget for many low-income households in Indonesia. In 2012, the Government of Indonesia was considering distributing identification cards to low-income households informing them about their eligibility for a national subsidized rice program, Raskin, in an effort to improve the program’s service delivery. The government requested evidence on the effectiveness of the cards before rolling them out nationwide.

In response, the study authors partnered with the government to conduct a fast, large-scale randomized evaluation of the Raskin ID cards in order to inform the government’s decision about whether to scale them up.

Raskin is Indonesia’s largest social benefit program and targets the poorest 30 percent of the population. At the time of the evaluation in 2012, Raskin-eligible households could purchase 15 kilograms of rice per month—about half of a typical household’s monthly rice consumption—at a subsidized price of one-fifth the market value. In 2012, the budget for Raskin was US$1.5 billion and the government distributed 3.4 million tons of subsidized rice to 17.5 million people. The program launched in 1998; at the time of this summary publication in 2019, it continued to operate under the name Rastra.

Administration of such a large benefit program posed many challenges:

- Lost rice (leakage): A substantial amount of rice intended for distribution disappeared before it reached people due to corruption, weak oversight, and inefficiencies. In 2012, eligible households received only about one-third of their entitled benefits.

Awareness: Raskin was a well-known program, but beneficiaries were not always aware of program rules and eligibility requirements.1

- Targeting: Local officials were supposed to use an official roster of eligible households to determine who could access the program, but instead they sometimes used their own discretion. In this study, 63 percent of ineligible households in the comparison group reported that they were able to purchase Raskin rice recently.

- Pricing: Local officials inflated prices. For example, eligible households in the comparison group in this study paid on average 42 percent more than the official subsidy price.

Details of the intervention

Information intervention

In collaboration with the Government of Indonesia, researchers conducted a randomized evaluation measuring the impact of sending Raskin-eligible households identification cards featuring information about the program. They designed the study to generate preliminary results in less than a year to inform the government’s decision about whether to roll out the cards nationwide.

The government mailed identification cards to Raskin-eligible households in 378 villages, randomly selected from 572 villages across three provinces. To better identify the different ways in which information had impacts on program delivery, the government randomly assigned villages to four variations of the intervention or a comparison group:

- Basic Cards: Eligible households received cards with information about their eligibility status and the quantity of subsidized rice that they were entitled to purchase.

- Basic + Price Cards: Eligible households received cards that included the same information as Basic Cards, plus the official subsidized price for Raskin rice.

- Cards + Public Information: In a subset of villages in the Basic Cards and Basic + Price Cards groups, lists of eligible households were posted in public gathering areas and information about the cards was played on a village loudspeaker.

- Cards to Lowest-Income Only: In a subset of villages in the Basic Cards and Basic + Price Cards groups, the government only sent cards to households in the lowest 10 percent of the income distribution (32 percent of eligible households).

- Comparison Group: In comparison villages, the government continued to run the program under the status quo with no identification cards.

Researchers conducted surveys of eligible and ineligible households two months, eight months, and eighteen months after the cards were mailed to measure key outcomes important to the national government, including the amount of rice received by eligible (and ineligible) households, the price they paid for the rice, and individuals’ understanding of their benefits.

Privatization of last-mile service delivery

In a randomly assigned 191 villages out of the same sample of 572, the central government introduced an auction procedure where citizens could bid for the right to distribute Raskin rice.

To facilitate bidding, a facilitator shared information about Raskin and the new distribution process with the community. A local committee was then organized to examine bids, choose the winner, and monitor distribution. A random subset of 96 villages was encouraged to have a minimum of three bids before the auction could proceed.

To control for the fact that the bidding intervention could improve program performance just by providing citizens with better information about Raskin, another 96 villages received an “information only” intervention, which provided citizens with the same program information and organized a committee to monitor Raskin distribution, but did not include the actual bidding process. The remaining 285 villages served as a comparison group and maintained the status quo rice distribution process.

Results and policy lessons

Information intervention

Identification cards with information about Raskin benefits increased the total benefits that eligible households received and reduced program leakages, despite incomplete program implementation.2

Information increased peoples’ knowledge of their eligibility status. Thirty-nine percent of eligible households that were sent cards knew their official eligibility status, relative to 30 percent in the comparison group—a nearly 30 percent increase.

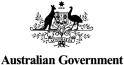

Information helped eligible households receive more benefits on average, and effects persisted over time. Eligible households in card villages received about 26 percent more total benefits on average relative to the comparison group in the two months prior to each survey (Figure 1).3 This increase was due to a combination of two factors: a 24 percent increase in the average quantity of rice received, and a 2.5 percent decrease in the average price paid. Increases in benefits persisted for up to eighteen months after the intervention.

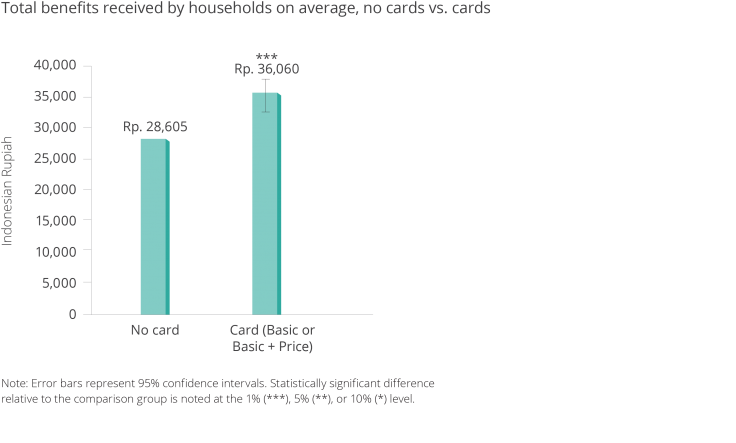

Adding the official price of rice to the cards doubled their impact. Eligible households in the Basic + Price Cards group received 24 percent more in total program benefits on average relative to the comparison group (a gain of Rp. 6,802 or US$0.69per month)—113 percent more than the gains seen by the BasicCards group (Figure 2).This difference was largely driven by those in the Basic + Price Cards group receiving a higher quantity of rice, rather than paying a lower price. This suggests that cards with price information were effective not because they encouraged officials to comply with the program’s pricing rules, but rather because they improved households’ bargaining power with local officials.

Publicizing information about program eligibility further increased households’ access to cards and knowledge of their eligibility status.Eligible households in the Card + Public Information group were19 percent more likely to actually receive a card and 50 percent more likely to present the card when picking up their rice compared to those in the card-only groups. Public information also increased eligible and ineligible households’ awareness of their own eligibility status.

Public information doubled the average increase in total benefits that eligible households received. Eligible households in the Cards+ Public Information group saw a 34 percent increase on average in total benefits relative to the comparison group (a gain of Rp.9,666 or US$0.99 per month)—100 percent more than the gains seen by card-only groups.

When cards were sent only to the lowest-income households, they had no impact on benefits for those households. Sending cards only to the poorest subset of eligible households led to fewer complaints to local leaders about program administration, but did not change the total benefits that these households received relative to the comparison group. When cards were sent only to the lowest-income households, those households fared no differently than when cards were sent to all eligible households. Eligible middle-income households only received more benefits when they were in villages in which all eligible households were sent cards.

Cards reduced program leakage by 33–58 percent. Eligible households that were sent cards received more benefits on average than the comparison group, ineligible households in card villages received no less, and government spending on the program did not change. Taken together, this implies that overall leakage within the program declined significantly. Researchers estimate that the cards reduced leakage by 1–1.6 kg of rice per eligible household, a 33–58 percent reduction in “lost” rice.

Privatization intervention

Offering villages the option to privatize rice distribution also improved program performance and reduced the price households paid for rice.

Overall, privatization improved program performance, though by a smaller magnitude. The bidding process led about 17 percent of villages to switch distributors. Villages generally prioritized suppliers who had relevant distribution skills as traders (who manage sales and distribution of goods for a living), access to transportation for distribution, and a savings account that could be used for business.

The bidding process reduced price markup by IDR 49 (US$0.01) relative to the information-only intervention, equivalent to an 8 percent reduction in markup. Requiring three bids further reduced markup by about IDR 74 (US$0.01).

In contrast, simply providing information without the bidding process had no effect on the price or quality of rice distributed, indicating that it was the bidding process and not increased transparency that led to improved program delivery.

Policy lessons

Delivering information to people can be a powerful tool for improving government service delivery. Providing information to people on benefits that they are entitled to through official channels like government ID cards can help balance the power between citizens and local officials, reducing opportunities for corruption and increasing access to social services. This is possible to achieve even for a well-established program like Raskin.

Making public information easily accessible can be empowering. Transparent eligibility information, through increasing people’s awareness of their own rights and the rights of others, can further equip people with the knowledge they need to access the benefits they are entitled to.

This type of information delivery can be highly cost-effective. The estimated increase in benefits that households received over the course of eighteen months was more than seven times the cost of the card program. The benefits of the cards exceeded the costs within just two months. This suggests that providing information to people about their rights to benefit from social services can be a cost-effective way to reduce corruption and improve access to services.

Policy influence

This study was developed in partnership with the Government of Indonesia with the explicit purpose of generating rigorous evidence to inform a national policy decision. Surveys were carefully timed to accommodate government deadlines and researchers quickly relayed results to policymakers in under a year.

In part based on these results, the government decided to scale up social assistance identification cards to 15.5 million households across the country, reaching over 65 million people in 2013. The cards included information on two other social benefit programs in addition to Raskin.Drawing on the results of another evaluation by J-PAL affiliated researchers, the scale-up included a local engagement process that enabled communities to reallocate cards for people who moved or for whom the community deemed too wealthy to receive the program.4

For more details, see the Evidence to Policy Case Study.