Report Cards: The Impact of Providing School and Child Test Scores on Educational Markets in Pakistan

- Parents

- Primary schools

- Students

- Enrollment and attendance

- Student learning

- Information

Policy issue

Private schooling has increased dramatically in low-income countries, from 11 percent of the market in 1990 to 22 percent in 2010. Yet, parents often lack enough information on school quality and performance to make an informed decision on the best school for their child, which can also allow higher quality private schools to charge more. Many policymakers believe that providing information is a powerful tool for improving public services, especially in the education sector. However, evidence is mixed and limited on the impact of information provision on school performance. Can more information improve the quality and cost of education?

Context of the evaluation

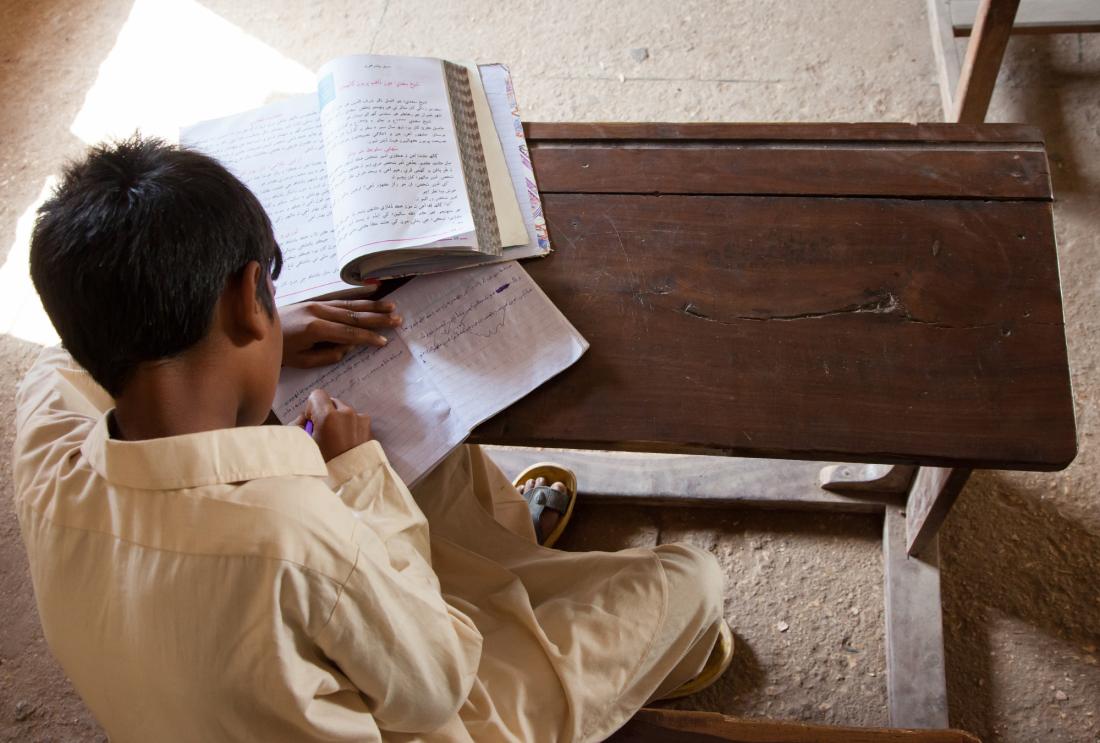

In Pakistan, over forty percent of enrolled children are enrolled in a private school. This study was conducted in rural villages in the Punjab province, the largest state in Pakistan with a population of seventy million in 2010. In Punjab, the number of private schools has grown from nearly 4,000 in 1983 to 47,000 in 2005. Sixty percent of the population in Punjab lived in a village with at least one private school in 2001.

The average village in the study had at least seven schools, four (sex-segregated) public schools, and three (coeducational) private schools. Distance was a major factor in choosing a school; increasing distance by just 500 meters reduced enrollment by up to three percentage points for boys and eleven for girls. Parents tended to be choosing between multiple private schools, which were often located closer to the village center, and a single public school, which was often located in the outskirts of the village.

Households in these villages spent an average of 3 to 5 percent of their monthly budget on each child’s schooling, with annual private school fees averaging about PKR 1,200 (approx. US$20). While learning levels were generally low, test scores varied greatly across schools and private schools had higher test scores on average. At the beginning of the study, parents’ perceptions of school quality were aligned with patterns in the test scores, though there was room for improvement. School enrollment varied by gender, with average village enrollment rate around 76 percent for boys and 65 percent for girls.

Details of the intervention

Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation to test the impact of providing report cards with child and school level test scores on school fees, student test scores, and enrollment rates. The study utilized data from Learning and Education Achievement in Punjab Schools Project (LEAPS), a multiyear study of education in Pakistan. Researchers chose a sample of 112 villages across three districts in the Punjab district, restricting to villages that had at least one private school in 2001.

Beginning in 2004, LEAPS tested 12,000 grade 3 children in English, Urdu, and mathematics. 56 of the 112 villages were randomly assigned to receive school report cards, which were distributed to schools and parents in September 2004. Researchers also conducted meetings with parents to explain the scores, as many parents were illiterate. The report cards included each child’s test scores along with how their scores compared to all other tested students. They also displayed average scores for all schools in the village, compared to all other tested schools. Researchers additionally conducted annual assessments of the schools to evaluate facilities and teachers, tracked household information for a subsample of students, and surveyed a subsample of parents to assess household educational investments. Initial tests and surveys of the children, schools, and households served as a baseline assessment; researchers conducted these surveys again one year after the program ended.

Results and policy lessons

Providing report cards on child and school performance to schools and parents reduced private school fees, improved test scores, and increased enrollment.

School Fees: Private school fees decreased by 17 percent, or PKR 187 (approx. US$3), from an average of PKR 1,080 (approx. US$18). The price declines were even greater among schools with initially high test scores. School fees among private schools with initial test scores in the top 40 percent decreased by nearly 25 percent, or PKR 294 (approx. US$5), from a baseline average of PKR 1,189 (approx. US$20). The different price reduction levels between high and low quality private schools support the theory that in the absence of information, high quality private schools relied on higher prices to signal their quality. The report cards caused parents’ perceptions of school quality to be better aligned with test scores, suggesting that parents’ changed perceptions of school performance affected the fees that schools charged.

Test Scores: Average test scores improved by 0.11 standard deviations in schools that received the report cards, reflecting an additional gain of 42 percent over the test score increase in comparison villages. Improvements from initially low scoring private schools drove the private school test score increase, while high scoring private schools did not improve. Test scores in public schools that received the report cards increased by 0.09 standard deviations on average, with similar improvements among low and high performing schools. For public schools and initially low scoring private schools, parents increased their engagement with schools, which may have pressured these schools to invest more in students and led to test score improvements. Public schools invested in better qualifications for teachers, while low-scoring private schools focused on increasing teaching time. Changes in private school test scores, and additionally school fees, were larger in villages where there was more school competition.

Enrollment: The primary school enrollment rate increased by 3 percentage points from 71 percent (a 4.5 percent increase), corresponding to approximately forty new students enrolling in school in each village. This growth was primarily driven by new students enrolling at the earliest grade levels. Other new students joined the fourth grade class—the cohort whose parents had previously received the report cards. This suggests that the higher quality and/or lower prices may have encouraged students who previously dropped out to re-enroll. There is little evidence that the program had an impact on children switching or dropping out, but low performing private schools were 13 percentage points more likely to close in villages with the program, accounting for observed declines in enrollment among these schools.

Cost-effectiveness: A relatively low-cost intervention, the entire program cost US$1 per child and led households to save US$3 per child on private school fees. Similarly, the gain in enrollment only cost US$22 per additional child, significantly lower than several programs currently regarded as quite successful in low-income countries.1

This study demonstrated that providing information about school quality can help improve price and performance across all schools. Additional research is needed to examine a broader set of outcomes beyond test performance and enrollment.

Akresh, Richard, Damien de Walque, and Harounan Kazianga. “Cash Transfers and Child Schooling: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation of the Role of Conditionality.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6340, 2013.