Private School Incentive Program in Pakistan

- Students

- Rural population

- Women and girls

- Enrollment and attendance

- Student learning

- Women’s/girls’ decision-making

- Scholarships

Policy issue

In many developing countries public schools are often highly dysfunctional or in some cases, entirely absent. Without access to adequate public education, many poor households will either forgo formal education or resort to informal institutions of uncertain value to meet the educational needs of their children. Though many developing country governments are seeking to improve educational access and quality, they face a variety of challenges, such as lack of trained teachers, school buildings, and textbooks. Private schools may be an alternative in places where the public education system is not providing the poor with adequate access to education. By subsidizing private education with public funds, it is hoped that private enterprises will have the incentive to maintain high enrollment rates and provide quality education to communities that would otherwise be neglected. Yet little is known about the effects of providing private school opportunities for poor families in developing countries.

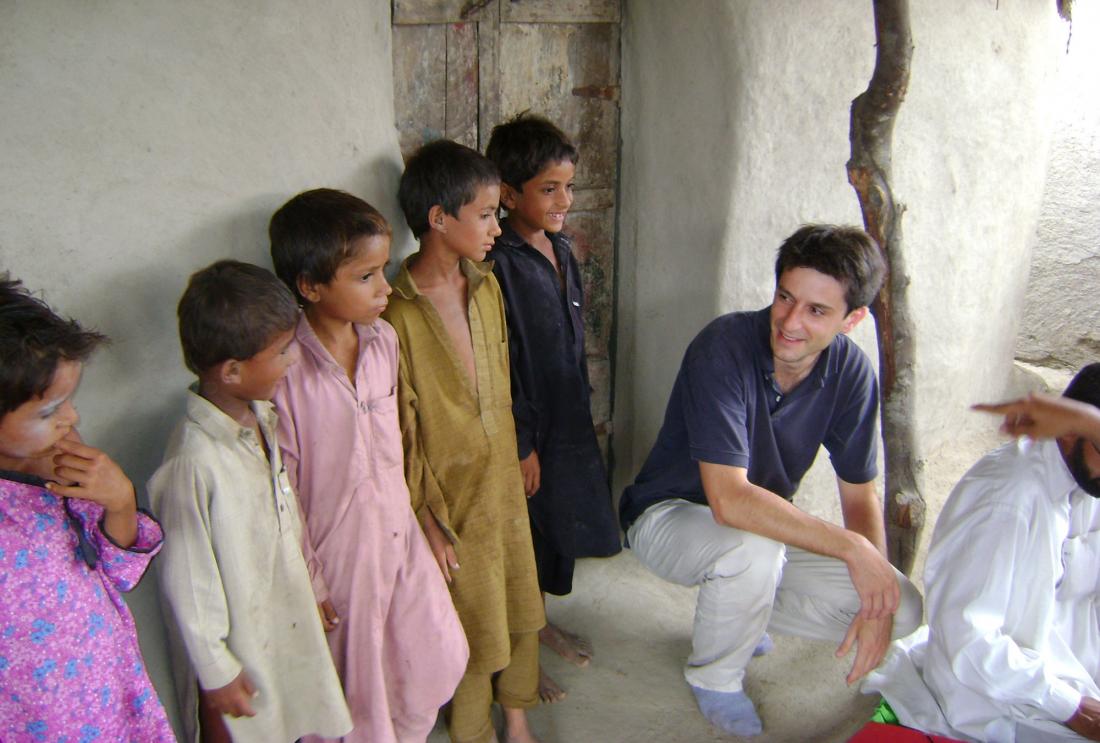

Context of the evaluation

This project takes place in rural communities in Sindh Province in Pakistan, where the vast majority of inhabitants are farmers. Public education in this region is poor, and girls tend to be particularly disadvantaged. In many areas, political insecurities have also made parents especially reluctant to allow girls to travel to outside of the community to attend school. In the absence of quality public schools nearby, low literacy rates in rural Sindh, particularly amongst women, are widespread. The government is attempting to improve education access and quality through innovative service delivery models, such as publicly subsidized private schools.

Details of the intervention

The Sindh Education Foundation (SEF), a quasi-governmental agency of the provincial government, partnered with private entrepreneurs to launch the Promoting Low-Cost Private Schooling in Rural Sindh (PPRS) program. Private entrepreneurs identified suitable villages to receive the PPRS program, based on the criterion that there be no other primary school within 1.5 km of the school being created. Entrepreneurs also identified appropriate school facilities and found qualified teachers, before submitting a proposal to SEF for approval. Those proposals which met the basic criterion received a subsidy from SEF for each student that enrolled. Communities were informed that SEF would be supporting the creation of private schools that would be free to all children in the community.

Among the qualifying communities, 100 were randomly assigned to receive equal subsidies for male and female students. To see whether incentivizing entrepreneurs would increase the enrollment of girls, 100 communities were randomly assigned to receive a larger subsidy for the enrollment of girls. In the remaining 63 communities, no PPRS schools were created. All children within treatment villages were able to enroll in the schools free of charge regardless of gender. All students in participating schools will be tested in reading and math. Enrollment and attendance information will also be collected on all children in the village.

Results and policy lessons

Results forthcoming.