Bridge Classes and Peer Networks Among Out-of-School Children in India

- Children

- Enrollment and attendance

- Student learning

- Social networks

- Recruitment and hiring

- Training

Policy issue

Between 1999 and 2006, the United Nations estimates that the number of un-enrolled primary-aged children fell by 30 million. However, 73 million children still do not attend a formal education program, and almost a quarter of these children are in South Asia.1 There are many potential reasons why children may not attend school. In places where educational resources are scarce, children may have to travel far distances to attend school, and school fees may prevent low-income families from enrolling their children in school. It is also possible that extended families and peer networks influence a child’s education actions, however more research is needed to understand the casual effects of peer relationships on the choice to participate or enroll in school.

Context of the evaluation

Gurgaon, where this study takes place, is a small city just outside of Delhi that has experienced large growth over the past 10 years due to Delhi’s urban sprawl. Though school enrollment rates in India are above 90%, in Gurgaon 47% of the children surveyed were not enrolled. Almost all of these children were from migrant families. Of the un-enrolled children, 96% of their parents said they were willing to send them to school, and only 1.4% of the children were working outside of their house.

Details of the intervention

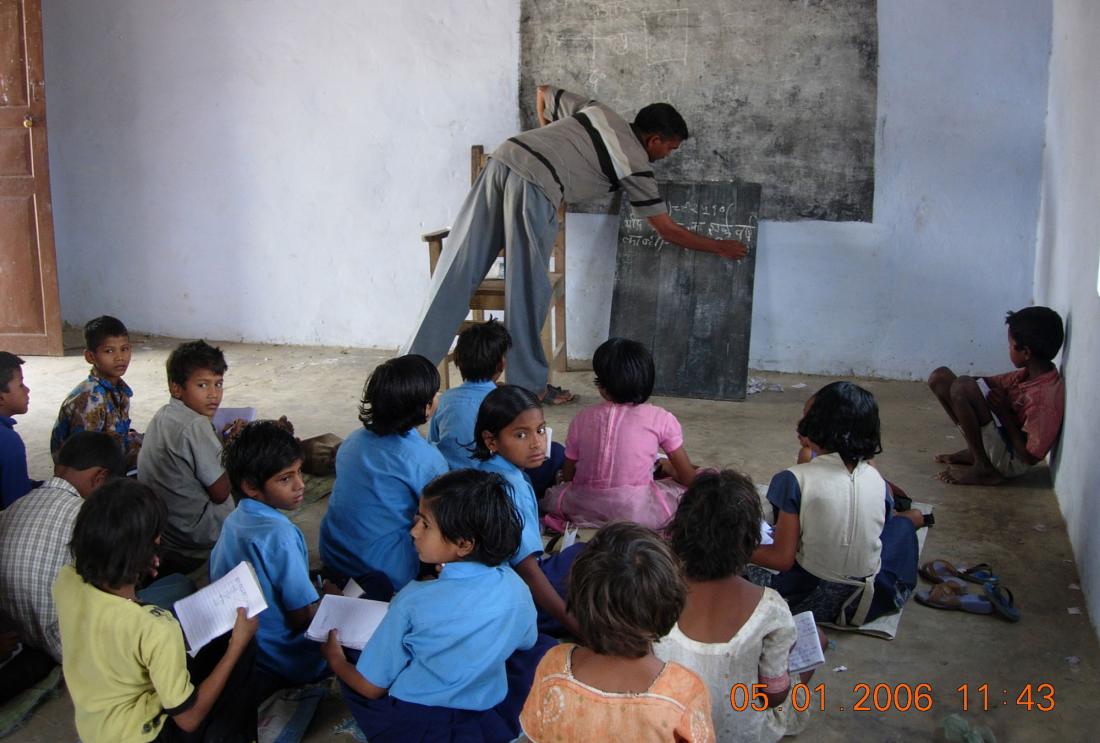

Researchers, in partnership with the Indian NGO Pratham, tested the effects of peer networks on the enrollment and attendance of a Bridge Course for out-of-school children. Pratham has implemented a Bridge Course program for a number of years in various areas in India. The Bridge Course is designed to give out-of-school children the opportunity to take informal classes for one year as a bridge into the formal school system. Pratham’s approach centers on the involvement of locally hired teachers who are trained in an intensive two-week program. Unlike teachers in the formal schooling system who may not share a common background with their students, Pratham’s model is designed so that the teachers can relate to the situations of the children they teach. Children in the Bridge Course are taught in groups of 20-25 students for three hours per day, six days per week. At the end of the year, Pratham assists the children and their families in enrolling in a local public school.

To identify social network connections, children were given a ‘friendship survey,’ which sought to identify relationships between peers and siblings. The survey allowed children to list their friends; it also asked children if they were friends with a list of pre-selected children. Attendance at the classes was measured through a team of monitors who visited the classes twice weekly.

Out-of-school children were identified through a community census in 17 different communities. One class was assigned to every 60 children in the 17 communities. The treatment consisted of actively recruiting 25 randomly selected children out of every 60 to attend the bridge program. Before the classes, the treated children were notified about when and where the class would be held. In addition, class teachers periodically re-visited the homes of treated children who were not attending to remind them of class and even walk them to class if necessary. Children not assigned to the treatment group were free to attend the classes as they wished, but they did not have the benefit of active recruitment.

Results and policy lessons

Attendance: Being in the treatment group and experiencing active recruitment to the program made a child 31% more likely to attend classes at all and 13% more likely to attend the class on a given day than a child who did not receive active recruitment. While boys and girls attended the classes in equal numbers, younger children were significantly more likely to attend.

Peer Networks Effects: Children who had a friend receiving the active recruitment treatment were 6.3 percentage points more likely to attend the classes. This effect is even stronger for children who have a sibling or a ‘mutual friend’ in the program, where mutual friendship is defined by both children identifying the other as a friend on the survey. Similarly, the amount that a peer or sibling participated in the program (defined as the number of days attended as a fraction of the total classes) has positive effects on a child’s own participation. A 10 percentage point increase in participation by a mutual friend increases a child’s participation by 4.2 percentage points, and a 10% increase in participation by a sibling increases a child’s participation by 6.1 percentage points.