When do Media Stations Support Political Accountability? A Field Experiment in Mexico

- Voters

- Electoral participation

- Transparency and accountability

- Elected Official Performance

- Voter Behavior

- Corruption and Leakages

- Audits

- Community participation

- Information

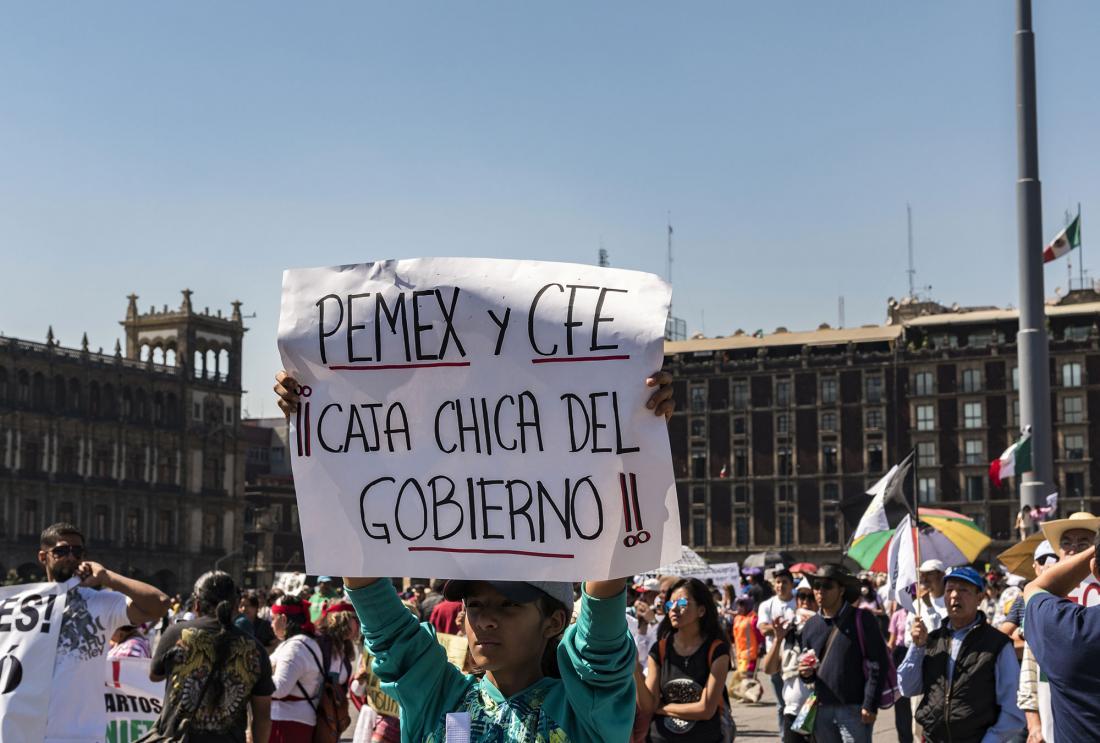

The importance of an informed electorate for electoral accountability is widely recognized. Researchers are using a randomized evaluation in Mexico to study the incentives media stations face when choosing to provide voters with indicators of their incumbent party’s performance in office.

Policy issue

Without information about politician performance in office, voters are liable to elect parties that are corrupt or unable to provide public goods. Yet, broadcast media and newspapers in developing countries often do not report such information, in part because it is expensive or difficult to access. If this is the case, media firms may only report information on politician performance when it is readily available, when it appeals to a significant share of their audience, or in response to competition from other outlets already reporting such news. What are the incentives for media stations to provide voters with information about their incumbent party’s performance in office? And how, in turn, does this impact voter and politician behavior?

Context of the evaluation

In Mexico, all municipalities are potentially subject to audits evaluating their use of federal funds. Each year, around 10 percent of municipalities are audited, and the results are made publicly available. The audit reports provide relevant information about mayoral malfeasance, such as unauthorized or misallocated spending and specific irregularities. For example, between 2007 and 2015, eight percent of funds in the average municipality were spent on projects not benefiting the poor, while a further six percent were spent in a corrupt manner.

A local NGO working on transparency produces an annual legislative scorecard detailing the performance of all federal deputies and senators over the preceding year. The scorecard ranks each representative in terms of their debate participation, agreements reached, initiatives proposed, initiatives approved, and session attendance. The scorecard provides rankings within each House, and also by state within each House.Although both forms of information are publicly available, media coverage of these reports is not widespread. This may be due partly to the fact that local media stations find it costly to access the information or lack the expertise to interpret complex, bureaucratic reports.

Details of the intervention

In partnership with two local NGOs, researchers are using a randomized evaluation to study the impact of providing media stations with simple, accessible information on the stations’ broadcasting activities, voter behavior, and politician performance. Researchers will randomly assign 292 media markets, defined as metropolitan areas or groups of towns covered by the same radio stations and newspapers, to a treatment group that receives the information or a comparison group that receives no information. The average media market contains around 200,000 voters. This study will focus on Mexico’s 1,148 AM and FM radio stations (that broadcast some news) and 456 newspapers (publishing at least once a week) located outside the Federal District of Mexico City that the researchers were able to contact. This represents 88 percent of all such media outlets.

Audit and legislator performance information will each be sent to treated media outlets once a year between 2016 and 2018. In the week after audit reports are publicly released, or when legislative activity indicators are computed before election periods, media stations within treatment markets will receive a simple factsheet, or “scorecard,” containing performance outcomes for all audited municipalities or federal representatives within the state. Within the treatment group, researchers will also randomize whether half or all of the media stations in the media market receive the scorecards in order to measure potential spillover effects. For example, if media stations that receive scorecards report on the audit results, this could cause competing outlets to also report similar information.

Researchers will analyze media output, using cutting edge audio and text scraping technologies, and survey media outlets to study the impact of the intervention on media outlet reporting, whether impacts differ between election and non-election years, whether other media outlets nearby receive the intervention, and whether outlets learn to publish such information over time. Researchers will also study whether such reporting ultimately impacts voting behavior, mayoral and legislator performance on the treatment indicators, and public goods provision.

Results and policy lessons

Project ongoing; results forthcoming.