Reducing Voter Registration Costs in France

- Urban population

- Electoral participation

- Information

- Targeting

One reason for persistently low voter turnout in established democracies may be high costs or barriers to voter registration. Researchers introduced three programs, information about voter registration and home registration visits, to identify whether making voter registration easier would affect voter participation. They also varied the timing of the programs: some voters were visited two to three months before the voter registration deadline and some were visited within one month of the deadline. Overall, they found that both types of visits increased registration and that home registration visits had a larger impact than information alone did. These results suggest that making voter registration easier could enhance political participation and improve the representation of marginalized groups in politics.

الموضوع الأساسي

In many longstanding democracies, elections regularly attract less than half of the voting-age population, and participation is often unequal among demographic groups. This trend raises concerns about how well elected officials and the policies they implement represent the wishes of all citizens. The time and effort required to participate in elections may contribute to low and unequal turnout. While voter registration in most democracies is automatic and done by the state, some democracies (including the United States and France) require citizens who wish to vote to register first. High registration costs might deter some potential voters from participating in elections, thus contributing to low and unequal voter turnout. However, citizens may also choose not to register simply because they are not interested in voting. If voters do not register because the cost of doing so is high, then reducing the costs of voter registration would likely increase both voter registration and voter turnout. Can making voter registration easier increase voter registration and/or voter turnout?

سياق التقييم

In France, citizens who wish to vote must register by submitting a form, an ID, and proof of address (e.g., a recent utility bill). Most people register in person at their local town hall, but they can also register by mail, online in some cities, or sending a third party to deliver their application to the town hall. Citizens must re-register every time they move. In 2012, the year of this evaluation, France held presidential and parliamentary elections. Registration deadlines occur well in advance of the election; the deadline to register for all of the 2012 elections was four months before the first election of the year. By that deadline, seven percent of all eligible people living in metropolitan France remained unregistered and around fifteen percent were “misregistered” at an old address. Misregistered voters are able to continue voting in their former polling station, but this requires traveling back or applying for a proxy vote, which makes voting more costly.

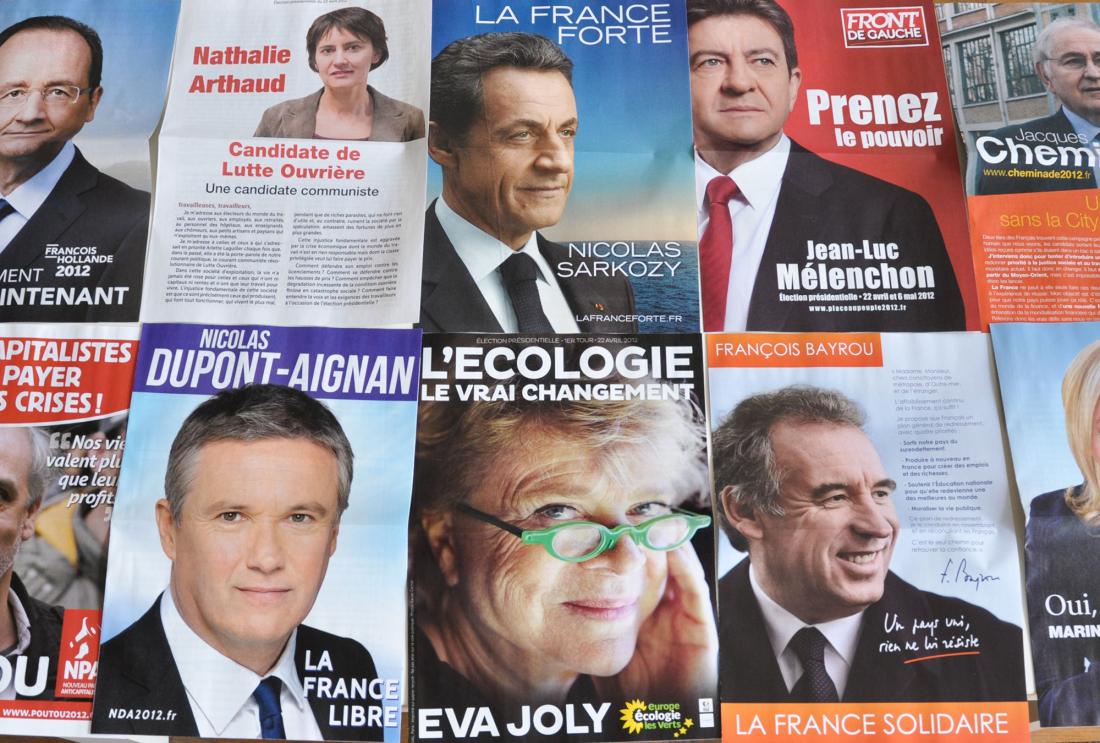

During the 2012 French presidential elections, 79 percent of registered voters participated in the first round in April, and 80 percent participated in the second round in May. François Hollande of the left-wing Parti Socialiste was elected president with 52 percent of the vote in the second round. The parliamentary elections occurred in June 2012. Fewer voters participated in these elections; 57 percent of registered voters voted in the first round, and 55 percent voted in the second round. The Parti Socialiste won in 57 percent of the constituencies.

معلومات تفصيلية عن التدخل

Researchers evaluated the impact of reduced voter registration costs on voter registration, voter turnout, and election results. The study took place in 44 precincts that were considered likely to host unregistered and misregistered citizens because of low voter turnout in previous elections. In these 44 precincts, researchers identified 4,118 apartment buildings that were likely to house unregistered and misregistered citizens. Of these buildings, researchers randomly assigned 3,092 to one of three treatment groups that received varying home visits aimed to increase voter registration, and 1,026 to a comparison group that did not receive any home visits.

- Canvassing: To test whether voters choose not to register because they do not have sufficient information about the process, volunteer canvassers encouraged people to register and provided information about the process in 1,030 apartments. A randomly selected half were visited two to three months before the registration deadline (early), and the other half were visited during the last month before the deadline (late). By comparing the effects of early and late visits, the researchers were able to determine whether procrastination plays a role in low voter registration (i.e., voters who learn about registration two months before the deadline might wait to register because the election is so far into the future).

- Home registration: To test whether voters choose not to register because registration is difficult, volunteer canvassers offered to register people at home, so that they would not have to go to the town hall, in 1,029 apartment buildings. A randomly selected half were visited early and the other half were visited late.

- Two visits:To test whether more frequent visits might be more effective, volunteer canvassers visited these 1,033 apartments twice. In a randomly selected half, the first visit was a canvassing visit and the second visit was a home registration visit. In the other half, residents received two home registration visits.

Researchers used voter registration lists to identify the effects of these interventions on voter registration. They also used attendance sheets signed by voters on each Election Day to identify the impact of these interventions on voter turnout.

النتائج والدروس المستفادة بشأن السياسات

Overall, visits of both types improved voter registration and turnout, suggesting that voters fail to register due to a lack of information and administrative cost. Information-only visits (canvassing) increased the number of people registered to vote by 0.022 per apartment, a 13 percent increase relative to the comparison group average of 0.168 people registered per apartment, suggesting that limited information does play a role in reducing voter registration. However, home registration visits increased the number of people registered to vote by 0.043 per apartment, a 26 percent increase relative to the comparison group. The fact that home registration was more effective than information alone suggests that both a lack of information and the administrative cost of registering impede voter registration. For both types of visits, late visits had a larger impact than early visits, possibly because early visits left more time to procrastinate or forget the discussion with the canvassers.

In addition to increasing voter registration, the home visits increased overall political interest and knowledge. Researchers estimate that turnout was high (93 percent) among those encouraged to register by the visits and did not differ from turnout rates among those would have registered on their own. This suggests that a lack of interest did not drive citizens’ failure to register, but instead, voter registration is difficult for these citizens.

Differences in the effects of these visits on registration rates suggest that the traditional registration process may exclude some groups of citizens from the electoral process, in particular those that are likely disadvantaged beyond their limited political participation. Less educated citizens and citizens speaking a language other than French at home who received the home visits were significantly more likely to register to vote than their counterparts in the comparison group were. Newly registered citizens were also likely to be younger and more likely to have immigrated to France than those citizens who already registered to vote. Finally, the researchers also found that newly registered citizens were more likely to have beliefs that fall on the left of the ideological spectrum.

Overall, the results suggest that removing the costs of registration would encourage greater participation, particularly among groups that face social and economic barriers to registering and voting. While increasing participation among these groups would have different effects on electoral outcomes depending on a variety of factors, encouraging more citizens to participate in elections would lead to election outcomes that are more in line with the popular opinion of the population as a whole.