Providing Information about Job Seekers' Skills to Increase Employment Outcomes in South Africa

- Job seekers

- Youth

- Earnings and income

- Employment

- Attitudes and norms

- Information

- Job counseling

- Certification

Youth unemployment rates are high across much of the world, and one reason cited for this is that employers have limited information about a candidate’s skill set, especially young candidates who lack work experience. In South Africa, researchers partnered with Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator to evaluate the impact of providing information about a job seeker’s skills on job seekers’ beliefs, search effort, and employment outcomes. Providing information to job seekers and prospective employers increased participants’ employment and earnings. Job seekers updated their beliefs and strategies for job search, and employers received information they valued.

Policy issue

Globally, there were nearly 68 million unemployed young people, aged 15-24, in 2020 and youth were three times more likely to be unemployed than adults.1 High youth unemployment rates are likely driven in part by employers’ lack of information about candidates’ technical and soft skills and their motivation. Formal education does not necessarily indicate one’s skills, especially in countries where student learning levels remain low.2 It is difficult for job seekers to signal their potential value to employers, especially for young job seekers who may lack references from previous employment. Additionally, it is costly for firms to hire the “wrong” candidate, as firing workers can require a lengthy and complex process. Previous research has typically explored whether information gaps about the job market exist and how to address them for either firms or for job seekers, but not both simultaneously. Can providing more information on a job seeker’s skills to both firms and job seekers reduce information gaps and improve young people’s employment outcomes?

Context of the evaluation

This study took place in Johannesburg, South Africa. South Africa has a high rate of youth unemployment, with over half of young people unemployed as of 2018. This rate is particularly high for urban Black youth that have limited post-secondary education, work experience, and access to referral networks. There are several factors that make hiring particularly tricky in Johannesburg. For one, information on young job seekers’ skills is limited, as many job seekers have no work experience several years after completing education and firms report that grades convey limited information about prospective job seekers’ skills. Furthermore, some job seekers will not accept lower-paying jobs, as commuting costs are high in Johannesburg and many job seekers who live with older family members have access to income from the state pension system. Additionally, firing a worker in South Africa requires a complex and lengthy process and can be challenged in court, so hiring a poor-performing candidate can be particularly costly for a firm.

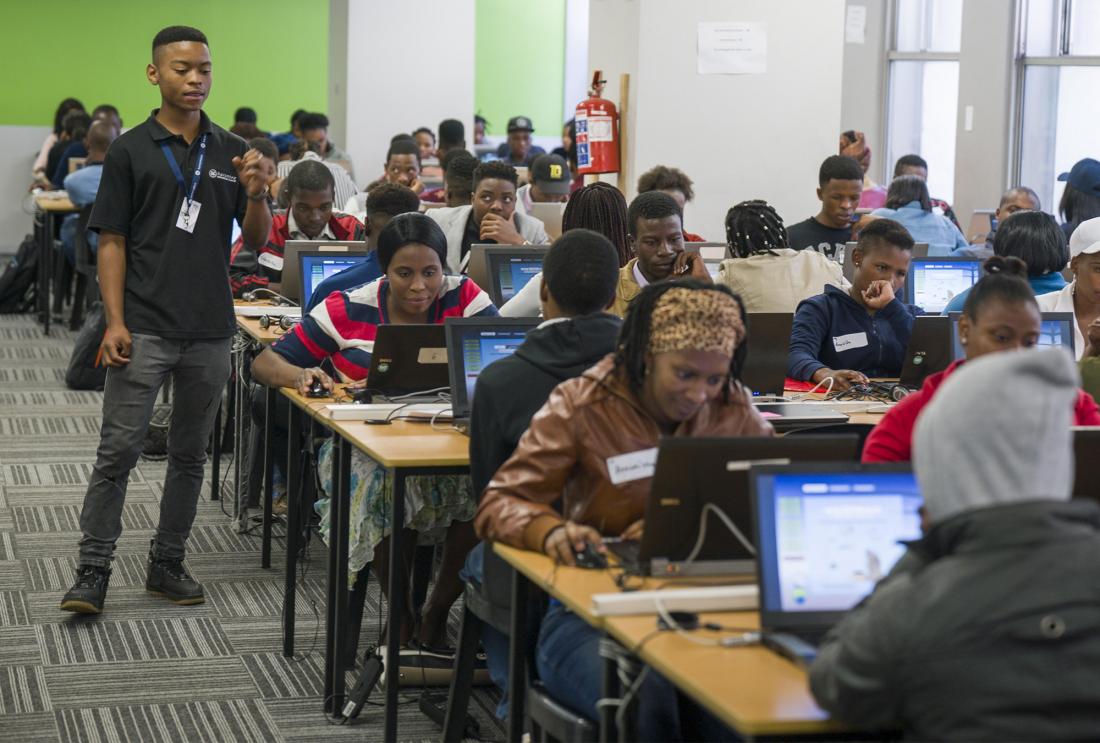

Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator is a social enterprise that builds solutions to address a mismatch of demand and supply in the youth labor market by connecting employers with first-time work seekers. Harambee serves roughly 100,000 unemployed youth annually. Harambee targets young adults between the ages of 18-29 who graduated from high school, are from low-income backgrounds, are currently unemployed, have limited formal sector work experience, and have actively searched for work in the past 6 months. Over two days, participants complete assessments to evaluate their cognitive skills, literacy, numeracy, and aptitude for different career types. Based on their assessment results, some individuals join a program that prepares them for and places them in jobs with Harambee’s partner employers.

This evaluation focused on individuals who had completed the initial assessments with Harambee, but were unlikely to receive placement into the full job readiness program. Nearly all participants were Black African and had completed secondary school, 38 percent had some post-secondary education, and 62 percent were female. Among them, 70 percent had previously worked, but only 9 percent had ever held a long-term job. Ninety-seven percent of participants had searched for work the week before, spending an average of 17 hours and 242 South African Rands (US$15.56 in 2016) searching.

Details of the intervention

Researchers partnered with Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator to evaluate the impact of providing information about a job seeker’s skills on beliefs about their skills, search effort, and employment outcomes. All participants received roughly one hour of job search counseling covering topics like how to prepare and dress for an interview. Over two, not necessarily consecutive days, 6,891 participants completed six assessments assessing numeracy, communication (both verbal and written), grit, focus, and planning skills. Between September 2016 and April 2017 and on the second day of assessments, researchers randomly selected by day if and how participants received the results from the assessments. To assess whether sharing this information with the job seekers only or encouraging applicants to share with prospective employers affected employment outcomes, researchers randomly assigned a third of participants to receive each of the following:

- Private feedback for job seekers only: Participants received a single copy of a black and white report with their assessment results, as well as a guide to interpreting the results and a group session to explain how these results might guide their job search process. The results ranked an individual’s scores on each assessment by top, middle, or bottom third relative to their peers, rather than providing an absolute score. The reports did not contain a participant’s name or other identifying information.

- Public feedback to share with prospective employers: Participants received a set of 20 printed reports of their relative scores on the assessments. These reports were printed in color, branded with both the Harambee and World Bank logos, and contained the job seeker’s name and national identity number. During the group session, participants received additional guidance on how to share this report with employers. Participants in this group also received a soft copy of their report via email.

- No feedback: Participants took the six assessments, but received no results on their performance. These participants served as the comparison group.

Additionally, to evaluate whether firms responded differently when provided with information on job seekers skills, researchers submitted a set of real job applications to firms’ job vacancies. They submitted multiple applications per vacancy, and randomized whether or not the applications included a public assessment report.

Researchers conducted surveys to collect information on participants’ demographics, employment and job search history, and beliefs about their skills and the returns to extra effort in their job search process. These surveys occurred between assessment and intervention, 2-3 days later, and 3-4 months later. To test if the branding of the public reports influenced how employers responded to the information provided, researchers also gave a smaller sample of participants reports identical in branding but without assessment results.

Results and policy lessons

Three to four months after job seekers took the assessment, participants’ who received public feedback to share with prospective employers had higher employment and earnings than those in the comparison group, while those who received private feedback had higher earnings, but less so than those who received public feedback. Additionally, both job seekers (in the public and private groups) and firms updated their beliefs and/or actions when they received information on job seekers’ certified skills.

Earnings and employment: Job seekers who received public certification were 5.2 percentage points (17.3 percent) more likely to be employed 3-4 months after the assessment than job seekers in the comparison group. Public certification also raised participants weekly earnings by 34 percent relative to the comparison group’s mean earnings of 159.3 South Africa Rands (US$10.24 in 2016). Hourly wages for those who received public certification increased by 20 percent relative to the control group’s mean of 9.84 South Africa Rands per hour (US$0.63). Additionally, public certification increased the probability of having a written contract—a formal job—by 2 percentage points (16.7 percent) relative to the comparison group. Receiving only private feedback did not increase job seekers’ employment chances or hours worked, and their earnings and hourly wages increased, but by less than for those who received public certifications.

Job seeker beliefs: Job seekers who received public certificates updated their beliefs about their skills to be closer to their measured skills—public certification increased the proportion of participants’ self-assessments matching their results from 0.39 to 0.55—but their reported self-esteem did not change.

Job seeker behavior: Job seekers who received public certificates used them: 70 percent reported sending the certificate with at least one job application in the previous 3-4 months. They were also 5 percentage points (31 percent) more likely to search for jobs that valued the skill in which they scored highest in the assessment.

Public vs private feedback: Job seekers who received private certificates updated their beliefs and altered the types of jobs they target in a similar way to job seekers who received public certificates. However, receiving private certificates that were less credible to firms had a smaller effect on participants’ labor market outcomes than public certificates.

Firm behavior: Firms gave 11 percent (1 percentage point) more interview invitations to applications that included skills certifications relative to applications without skills certifications, suggesting that firms acquired additional information about job seekers’ skills from the certificates in the initial round of reviewing applications.

Results suggest that access to information on job seekers’ skills was a barrier to hiring for both job seekers and firms in South Africa, and providing skills certificates updated both sides’ beliefs and behavior. The intervention was also cost-effective, as the average effect on participants’ earnings in the first three months after the assessment is 2.3 times the average cost per assessment and certification.

Informed by this study, Harambee integrated a modified version of this intervention into their operations in late 2019.3 The study results have also informed the researchers’ engagement with government departments that are considering similar interventions, including through this implementation guide that details how organizations may roll out a skills certificate program. Additionally, after learning about the results of this study, the City of Cape Town’s Expanded Public Works Program now offers participants of certain programs the opportunity to complete a literacy and numeracy skills assessment and receive a certificate which they may include in their future job applications.