Improving Rug Firm Performance through Exporting in Egypt

- Small and medium enterprises

- Earnings and income

- Market access

In recent decades, governments, nonprofits, and donors have increasingly invested resources in market access initiatives targeted at small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). To examine how exporting affects the profits and productivity of SMEs, researchers partnered with Aid to Artisans (ATA), a US-based nonprofit, and Hamis Carpets, an Egypt-based distributor, to provide small-scale rug manufacturers the opportunity to export to high-income countries. Offering small firms the opportunity to export rugs to high-income markets increased firm profits through improvements in firm’s technical knowledge, efficiency, and product quality.

Problema de política pública

In recent decades, governments, nonprofits, and donors have increasingly invested resources in market access initiatives targeted at small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These initiatives aim to improve livelihoods for firm owners and workers in SMEs and promote exporting by matching domestic firms with foreign buyers. In theory, access to high-income markets may help firms in low- and middle-income countries not only improve their profits but also promote “learning-by-exporting.” By repeatedly engaging with buyers in foreign markets, who often demand higher quality standards, firms can improve their technical skills and efficiency. However, evidence remains limited on whether “learning-by-exporting” occurs and how access to export markets impacts SMEs.

Contexto de la evaluación

Egypt has a strong historical reputation for producing flatweave rugs. In 2013, Egypt was the eleventh largest global producer of carpets and rugs, with a total annual production of US$734 million. At that time, more than 17,000 Egyptians worked in the carpet and rug industry, representing 7 percent of total world employment in this industry and 1.7 percent of total manufacturing employment in Egypt.

Fowa, a peri-urban town in Egypt, is known for its “carpet cluster,” where hundreds of small firms use wooden foot treadle looms to manufacture flat-weave rugs. The majority of firms in Fowa consist of a single owner who operates out of a rented space or home. In most cases, the firm has no other full-time employees. For sales to the domestic market, firms receive an average of LE42.5 (about US$7 at the time of the evaluation) for each rug they produce. Prior to the evaluation, participating firms’ monthly profits from the rug business averaged LE646 (US$102). Only about 12 percent of firms had ever knowingly produced rugs for the export market.

Aid to Artisans (ATA), a United States-based nonprofit that aims to create economic opportunities for handicraft producers in low- and middle-income countries, began a market access program in Egypt to match local rug producers with foreign buyers in 2009. ATA worked closely with Hamis Carpets—the largest rug intermediary in Fowa—to design and market carpets for sale in foreign markets. With the support of ATA, Hamis Carpets generated export orders from clients in high-income countries.

Detalles de la intervención

Researchers partnered with ATA and Hamis Carpets to evaluate the impact of exporting on the profits and productivity of small rug-producing firms in Fowa, Egypt. Hamis Carpets, with marketing support from ATA, secured sustained export orders from rug buyers in the United States and Europe. Researchers then provided a random subset of local firms the opportunity to fill these orders. Firms were eligible to participate if they had fewer than five employees, purchased their own materials, and had never previously worked with Hamis Carpets. Among 219 eligible rug producers, researchers randomly assigned 74 firms to the treatment group of exporting firms and the remaining 145 served as the comparison group.

Hamis Carpets and the foreign buyers established pricing, delivery timing, and product specifications. Small rug firms in the treatment group produced requested rugs, while Hamis Carpets coordinated with foreign markets to complete exporting orders. Although each firm had been randomly assigned to receive the initial order request, Hamis Carpets could place subsequent orders with exporting firms based on firm performance and buyers’ continued interest.

Researchers periodically surveyed all firms over a three-year period between 2011 and 2014 to assess productivity and knowledge flows between buyers, intermediaries, and producers. A master artisan intermittently measured the quality of firms’ rugs along eleven dimensions including weight, touch, design accuracy, and more. At the end of the intervention period, researchers also invited all firms to a rented workshop location (or a “quality lab”) and asked them to produce an identical rug using the same loom and inputs. Comparing these identical specification rugs allowed researchers to compare quality and productivity between exporting firms and comparison firms using the same equipment.

Resultados y lecciones de la política pública

Offering small rug producers in Egypt opportunities to export rugs to high-income markets increased firm profits through improvements in firms’ technical knowledge, efficiency, and product quality.

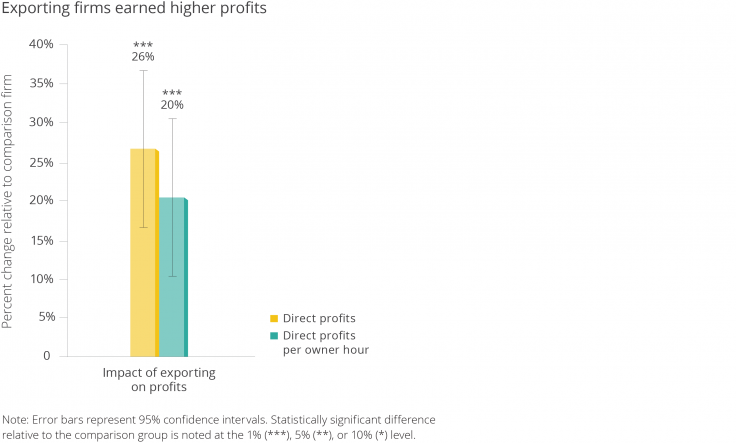

Profits: Offering small firms the opportunity to export rugs increased monthly profits by 26 percent relative to the comparison group. While exporting firm owners increased their hours worked by about 5 percent, they experienced a 43 percent increase in prices received for each rug produced. The effect of market access was large relative to the effect of other interventions targeted at firms, such as credit access and business training programs, which have had limited impacts on profits for similar firms.

Production: Providing opportunities to export improved firms’ technical ability and efficiency to produce high-quality rugs. When a master artisan assessed rug quality on a scale from 1 (lowest quality) to 5 (highest quality), exporting firms scored 0.79 points higher than comparison firms, who scored 2.96 points on average.

When all firms were asked to prepare similar rugs using the same equipment, those offered export orders produced the rugs faster and with higher quality than comparison firms, suggesting improvements in efficiency.

Learning: Improvements in quality were a result of “learning-by-exporting.” While there were no immediate improvements in quality or productivity after the exporting intervention, significant improvements appeared after five months. This suggests that firms learned and adjusted their production practices as a result of engaging with buyers in foreign markets. In particular, knowledge transfers between foreign buyers, local producers, and the firm that connected foreign buyers and local producers partly explained the eventual improvements in quality and efficiency.

These results suggest that greater access to foreign markets may be more valuable than greater access to domestic markets for SME development. Access to foreign, high-income markets exposes firms to sophisticated buyers who have higher quality standards than many domestic buyers, are often willing to pay more for higher quality products, and can be willing to help local producers by transferring knowledge. This can lead to greater quality, productivity, and profitability.

In addition, increasing access to export markets for SMEs in low- and middle-income countries comes in many forms, and more research is needed to understand the effectiveness of other interventions or policies that reduce barriers to exporting, including by reducing tariffs or other trade costs.