Improving Financial Access through Microcredit for Women in Mexico

Microcredit is widely believed to create opportunities for entrepreneurs and families to improve their economic and social well-being. Researchers expanded microcredit offerings in Sonora, Mexico to evaluate the effect of improved credit access on economic and social outcome. They found that microcredit increased access to formal financial services and enabled some businesses to expand, but did not increase household income or prompt new business creation.

Policy issue

Microcredit is one of the most visible innovations in poverty alleviation programming in the last half-century, and in three decades it has grown dramatically. Now with more than 200 million borrowers,1 microcredit has been successful in bringing formal financial services to the poor. While microcredit has received praise for its potential to lift clients out of poverty, this recognition is often based on generalizations about the microfinance movement or on simple comparisons of borrowers and non-borrowers. Attempts to determine the true impact of microcredit programs are complicated by the fact that the choice to become a microfinance borrower may itself be a sign of increased ambition and ability to improve one' s economic situation. To date, few studies have rigorously quantified the impacts of microcredit loans on the beneficiaries and their communities.

Context of the evaluation

The study took place in the northern Mexican state of Sonora in the cities of Nogales, Caborca, and Agua Prieta, as well as surrounding towns. Although agriculture, mining, and wage labor in factories along the U.S. border provide some employment opportunities, most people are underemployed and strive to make ends meet through various informal employment opportunities. Many residents lack the income or collateral to qualify for loans from traditional bank services.

In 1990, Compartamos Banco began offering credit in an effort to promote economic development by spurring the growth of micro-businesses. It converted to a commercial bank in 2006 and became a publicly traded company in 2007. Today, Compartamos Banco is the largest microfinance institution in Mexico with branches in every state and over two million borrowers. Crédito Mujer, the principal village banking product of Compartamos is offered to groups of 10 to 50 Mexican women over the age of 18 who either have some kind of business or would like to use the loan money to start one. Compartamos does not verify whether individuals are currently engaged in an income-generating activity or planning to start one once given the loan, instead they depend on other group members to screen out uncreditworthy women.

Details of the intervention

This project evaluates the social and economic impact of access to credit, taking advantage of Compartamos' decision to offer Crédito Mujer in the north of Sonora, where it had not previously offered loans. Researchers divided the study region into 250 geographic clusters and then randomly assigned half to a treatment group and the other half to a comparison group. In treatment clusters, Compartamos began offering loans in April 2009: loan officers targeted self-reported female entrepreneurs and used a variety of channels, including door-to-door promotion, radio ads, promotional events, and distributing fliers, to promote the Crédito Mujer product. Crédito Mujer loans in the sample ranged from1,500 pesos to 27,000 pesos (US$125 to US$2,250) with first-time borrowers qualifying for lower amounts. The annualized interest rate for Crédito Mujer was approximately 110 percent in 2009 and borrowers repaid the loans over 16 weekly payments. In comparison group areas, Compartamos did not begin offering credit until almost 3 years later.

Baseline and endline data is from socioeconomic surveys administered to women 18-60 who had or were likely to start a business in both treatment and comparison areas. Researchers conducted follow-up surveys between 2011 and 2012, an average of 26 months after Compartamos entered the treatment areas.

Results and policy lessons

Loan take-up and financial access: Women in treatment areas reported taking out more loans and borrowing more from Compartamos than their peers in comparison areas. Around 17 percent of women in treatment areas borrowed from Compartamos, compared to 5.8 percent of women in comparison areas. In areas where Compartamos offered Crédito Mujer, informal borrowing increased to 6.2 percent of households, a 1.1 percentage point increase over areas where Compartamos did offer the loans. Researchers theorized that this may be because Compartamos loans did not fully meet credit demands, or potentially because some borrowers sought credit elsewhere to pay off their Compartamos debt.

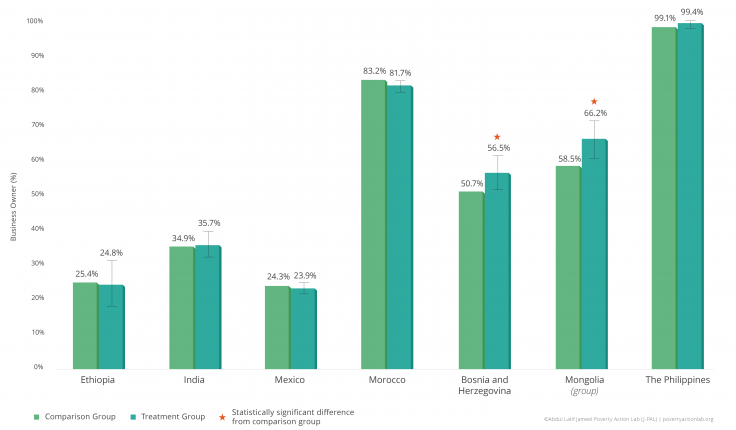

Business activities: Expanded credit access did not affect business ownership, but it did increase some business activities. In the two weeks before the endline household survey, women in treatment groups reported average sales 27 percent larger than those in comparison groups, and spent 36 percent more on their businesses. However, there was no increase in business profits.

Household finances and well-being: While there were no significant changes in household income, expanded credit access had generally positive effects on well-being. In treatment areas, depression fell, trust in others rose, and female participation household decision-making increased.

Additionally, households in treatment villages were better able to avoid selling assets in order to pay down debt than their peers in comparison villages. There was no strong evidence that credit expansion caused a significant number of people to experience negative microcredit effects, such as having to sell household items to pay off debts.

While researchers found little evidence to support microcredit' s negative effects in this context, they did observe that microcredit generally had a larger effect on households that already enjoyed relatively high business revenues or profits, as well as on households where female borrowers already had high decision-making power. In this context, access to microcredit offered improved happiness and increased borrowers' trust in people more for women who already reported higher levels of happiness and trust.

Overall, increased access to microcredit allowed some existing businesses to expand, and enabled customers to use formal financial services to manage their cash flows over time, although it did not increase their business profits or prompt people to start new businesses. Further research is needed to explore potential screening criteria or effective guidance to first-time borrowers.

Note: Green (red) arrows represent statistically significant positive (negative) differences in outcomes between the treatment and comparison groups at the 90 percent confidence level or higher, dashes represent no statistically significant difference. For more detailed information on the outcomes summarized in this table, please see the full footnote for Table 2 on page 11 of "Where Credit is Due."

Angelucci, Manuela, Dean Karlan, and Jonathan Zinman. 2015. "Microcredit Impacts: Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 151-182.