Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for Workers without Dependent Children in the United States

The Earned Income Tax Credit, one of the largest programs providing income support to low-income workers in the United States, provides little support for workers without dependent children.1 The Paycheck Plus Program in New York City tests the effects of expanded EITC eligibility for 6,000 low-income single adults without dependent children for three years, starting in 2015. MDRC partnered with NYC Opportunity, the NYC Human Resources Administration and Food Bank for NYC to design, implement, and evaluate the program. MDRC researchers found that three years of Paycheck Plus in New York City increased income, employment, tax credit receipt, and payment of child support. Research on Paycheck Plus at a second site in Atlanta is still ongoing.

Policy issue

Over 26 million families received the EITC in the 2015 tax year. For someone not working, the credit creates an incentive to work, since it increases the payoff to working. For someone working with earnings in the phase-in part of the schedule, they might be encouraged to work because they gain more benefits as they earn more (the substitution effect), but might also work less because they receive additional unearned income (the income effect). In the phase-out region, work is potentially discouraged since EITC benefits are reduced as earnings increase. The credit is therefore expected to increase employment rates, but its overall effect on earnings is not easy to predict given the different incentives it creates for individuals earning different amounts. Policymakers on both sides of the aisle have recognized the value of the EITC as a policy that both reduces poverty and encourages work, and it has been expanded substantially in recent decades, particularly for working adults with dependent children.

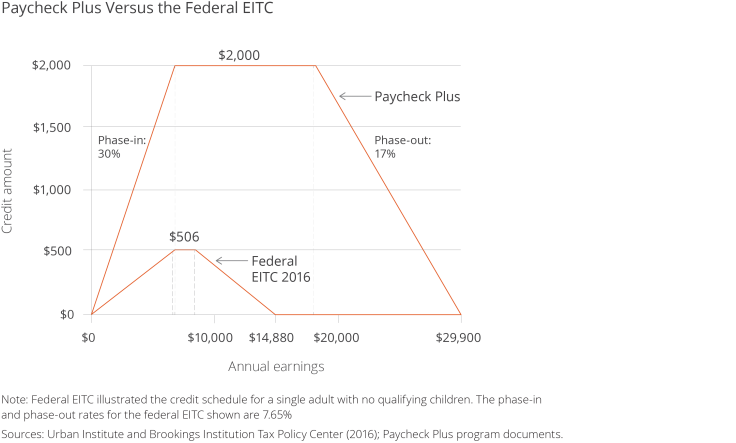

As shown in this graph, the federal EITC for single adults without dependent children – the lower line – has a phase-in range, where the amount of the credit increases steadily as earnings increase, to supplement the earnings of eligible individuals; then it reaches a small plateau range, where the credit remains constant as earnings increase; and finally, the credit is phased out as earnings increase further. Paycheck Plus—the upper line— has a much more generous phase-in rate, a much larger maximum benefit of $2000 as opposed to $506, a longer plateau, and a longer phase-out range.

However, the EITC provides little support for workers without dependent children: in 2016, for example, an individual working full time for the full year at $9 per hour would earn too much to qualify for any benefits. Paycheck Plus tests the effects of a much more generous tax credit for single adults without dependent children relative to the credit they are eligible for under the federal EITC.

Context of the evaluation

Paycheck Plus is being evaluated using a randomized evaluation in two major American cities: New York City, starting in 2015, and Atlanta, Georgia starting with the 2017 tax season. Between September 2013 and February 2014, MDRC recruited over 6,000 low-income, single adults without dependent children in New York City: about 60 percent were men, half were under 35, one-fifth had not obtained a high school diploma or equivalent, one-fifth had been incarcerated at some point in the past, and one-tenth were noncustodial parents. About one-third had no earnings and another one-third had earned less than $7,000 in the year before enrollment.

Details of the intervention

Paycheck Plus was designed to mimic the federal EITC, meaning that the same criteria were applied when calculating eligibility for the bonus: an individual must file federal income taxes and have earned income in the relevant range to be eligible for the bonus. After filing federal taxes in 2015, 2016, and 2017, participants were eligible to apply after each year but did not have to apply all three years to receive the Paycheck Plus bonus. Participants were recruited through Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) sites and NYC Human Resources Administration welfare programs. Participants’ bonus payments were deposited to a bank account or to a debit card.

Half of participants were assigned at random to a group offered the Paycheck Plus enhanced bonus and half were assigned to a group not offered the program but still able to claim existing federal and state tax credits. To remind participants to apply for the bonus each year, 12 rounds of reminders were sent by letter, e-mail, text message, and phone call. The program established two-way contact with about three-quarters of treatment group participants. There was concern that some individuals might have difficulty finding work. The study therefore included a second randomized evaluation: of the participants reporting less than $10,000 in annual earnings in the past year, half were randomly assigned to an “employment-referral group” who received information about employment services. The other half were offered the bonus without additional information. This means researchers will be able to test the additional effect of a low-touch employment service referral on top of the Paycheck Plus bonus.

Demographic data were collected from participants in a baseline survey. Researchers will measure outcomes using unemployment insurance records, child support payment records, and tax records from the IRS (including W-2 and 1099 forms), and a follow-up survey to examine a wider range of outcomes.

Results and policy lessons

Results discussed here are findings from Paycheck Plus in New York City. Researchers followed study participants for three years after enrollment to assess the effects of Paycheck Plus on income, employment, and earnings using administrative data; and on a wider range of outcomes using a 32-month survey.

Effect on receiving tax credits and tax filing: Paycheck Plus led to an increase in the number of participants who filed taxes in all three years. The tax filing rate for both the treatment and control groups decreased over time, but in the third year, 2017, individuals in the treatment group were 5.5 percentage points more likely to file taxes, relative to a control group mean of 61.6 (an 8.9 percent increase).

Paycheck Plus also increased federal EITC receipt in all three years. EITC receipt increased by 3.9 percentage points in 2015 from a control mean of 34.8; 2.7 percentage points in 2016 from a control mean of 30.1; and 2.5 percentage points in 2017 from a control mean of 27.0 (increases of eleven percent, nine percent, and nine percent respectively).

About 64 percent of eligible individuals in the treatment group received bonuses in the first year (2015), 57 percent received bonuses in the second year (2016), and 54 percent received bonuses in the third year (2017). These rates are comparable with federal EITC take-up rates for singles without dependent children.

Effect on income: Paycheck plus increased after-bonus income among those who received a bonus, although the effect was driven largely by women and the lowest income earners. Among those who received a bonus in a given year, the average amount received was $1,400 (out of a maximum possible amount of $2,000). On average over the three-year period, individuals in the treatment group saw a statistically significant increase in after-bonus income of six percent (from a control mean of $11,419) as compared to the control group.

Paycheck Plus reduced the incidence of severe poverty by 3.4 percentage points from the control mean of 32.6 percent (a decrease of 10.4 percent). However, the program had no effect on overall poverty rate, as most of the effect was to move individuals from severe poverty (less than 50 percent of the poverty line) to less-severe poverty (between 50 percent and 100 percent of the poverty line).

Women were more likely to receive the bonus than men in all three years. In 2017, 38 percent of eligible women in the study received a bonus compared to 25 percent of eligible men in the study. This is largely because women were more likely to file taxes and apply for bonuses. Over the three-year period, the program increased women’s average after-bonus earnings to $13,527 from a control mean of $12,427 (an increase of 8.9 percent), while men saw no statistically significant effect.

The effect of Paycheck Plus on earnings differed by earnings level. The program led to statistically significant increases in the bottom half of the earnings distribution, while there were no effects on earnings in the top half of the income distribution.

Effect on employment: Paycheck Plus did not increase employment rates in 2015, but it did increase employment rates in 2016 and 2017. Over the full three-year period, the program increased the average annual employment rate by 1.9 percentage points over the control mean of 75.4 (an increase of 2.5 percent).

The effects on employment were concentrated among women and among men who had been incarcerated or who were noncustodial parents ordered to pay child support. In year three, Paycheck Plus increased employment rates for men who had been incarcerated or who were noncustodial parents by 5.8 percentage points over a control mean of 56.6 (an increase of 10.2 percent). Effects on employment were consistently larger for women than for men across all three years. On average over the three-year period, the employment rate for women in the treatment group was 3.2 percentage points higher than the control group mean of 80.0 percent, an increase of four percent.

The bonus did not reduce employment among those who had higher earnings when they enrolled in the study.

For the secondary evaluation with employment service referrals, the group offered the bonus and given the additional information about employment services saw an increase in employment rates as compared to the control group, but no significant increase as compared to the group receiving the bonus alone. It is therefore not possible to conclude that the added services led to larger employment effects.

Effect on child support payments: Paycheck Plus increased the payment of child support in 2015 and 2016. In 2015, about 73 percent of non-custodial parents in the treatment group made a payment during the year, a 7.6 percentage point increase from a control mean of 65 percent, an increase of 12.3 percent. The treatment group paid, on average, $172 per month in child support, an increase of $48, or 38.7 percent, over the control mean of $124. In 2016, the effect on making a payment in was similar in size, but there was no effect on the amount paid.

Effects on health: Paycheck Plus had no effect on self-reported physical health, nor did it result in any increase in self-reported happiness. Paycheck plus did, however, reduce the percentage of respondents at risk of depression or anxiety. About 38 percent of the program group was at risk for depression or anxiety, a decrease of 3.1 percentage points from a control mean of 41 percent (a 7.9 percent decrease).

Policy implications

The findings for Paycheck Plus in New York City are consistent with other research on the federal EITC, indicating that an effective work-based safety net program can increase incomes for low-income individuals and families by encouraging and rewarding work. Work-based assistance is not appropriate for all low-income individuals, such as some people with disabilities or older people, and may need to be supplemented with other sources of income support for the jobless, especially during times of recession. Findings from Paycheck Plus in Atlanta will add to the evidence about the potential effects of expanding the EITC for low-income workers without dependent children.

Courtin, Emilie; Allen, Heidi L; Katz, Lawrence F; Miller, Cynthia; Aloisi, Kali; Muennig, Peter; (2021) Effect of Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit to Americans without Dependent Children on Psychological Distress (Paycheck Plus): A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Epidemiology. ISSN 0002-9262 https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4660394

Miller, Cynthia, Lawrence F. Katz, Gilda Azurdia, Adam Isen, and Caroline Schultz. 2017. “Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for Workers Without Dependent Children: Interim Findings from the Paycheck Plus Demonstration in New York City.” MDRC; https://www.mdrc.org/publication/expanding-earned-income-tax-credit-workers-without-dependent-children.

Miller, Cynthia, Lawrence F. Katz, Gilda Azurdia, Adam Isen, Caroline Schultz, and Kali Aloisi. 2018. “Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for Singles: Final Impact Findings from the Paycheck Plus Demonstration in New York City” MDRC; https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/PaycheckPlus_FinalReport_0.pdf