Creating Incentives to Decrease Water Waste in Zambia

- Urban population

- Information

- Natural resource management

- Water, sanitation, and hygiene

- Pricing and fees

Excessive water use generates negative impacts on the environment, and many urban utilities structure pricing in order to discourage wasteful consumption of this resource. Researchers partnered with a water utility in Zambia to test and identify the best mechanisms to encourage water conservation. They found that targeting incentives to higher household water consumers might be an effective way to reduce water consumption.

Policy issue

Sustainable growth requires the management of scarce natural resources. Water scarcity, for example, is a pressing problem, particularly in arid and semiarid countries. Many urban utilities have adopted different pricing structures, such as charging a greater price at higher levels of consumption, as a way to discourage wasteful water usage. The effectiveness of these strategies, however, will depend on the behavior of all members in the household.

Each person inside a household enjoys the benefits of consuming water while sharing the costs with other family members through the household’s water bill. Since it is difficult to monitor how much each member consumes, conservation efforts will depend on the extent to which individuals consider how their choices affect other members. Families with less internal cooperation, for example, can be less sensitive to price changes and more likely to over-consume than households that cooperate well with each other. How can policymakers encourage households to collectively reduce their water usage?

Context of the evaluation

The Southern Water and Sewerage Company (SWSC) provides piped water to residents of Livingstone, Zambia. Households are billed based on monthly meter readings and charged according to an increasing block tariff–i.e., past a set level of usage, the price for each additional unit of water increases, and continues to increase at certain levels. At the time of this evaluation, households in the study sample spent around US$9.50 monthly, or 4 percent of their median income, on water.

This evaluation focused on examining water use dynamics between the husband and wife in a household. Husbands paid the water bills in about 53 percent of households, and in about 80 percent, wives used more water than their husbands.

Details of the intervention

Researchers conducted a randomized evaluation in partnership with SWSC to assess the impact of financial incentives and information on households’ water use. Researchers randomly assigned 1,282 households to one or more of three groups.

- Lottery + price information: Half of all 1,282 households were eligible for a lottery, conditional on saving water. All households that were randomly assigned to participate in the lottery also received information about water prices, as described below. Households that reduced their monthly water usage by at least 30 percent relative to their average water usage in the previous two months were automatically entered into a lottery. Each month, one in every twenty qualifying households won ZMW 300 (about US$30). By encouraging households to reduce their water use in exchange for a monetary reward, the probability of winning the lottery effectively served as an increase in the price of water. To gather additional insight on household dynamics, researchers varied who received information on the lottery. In one-third of households, both spouses learned about the lottery, incentivizing the entire household to conserve. In another third of households, only the wife learned about the lottery, and in the remaining third, only the husband did. In households in which only the wife or husband were informed, these individuals were also paid privately if they met the water use reduction threshold and won the lottery (individual incentive). This randomization generated an increase in a specific individual’s price for water, which is usually infeasible because a water utility only observes the total water use for a household (or technically, housing structure attached to a unique meter).

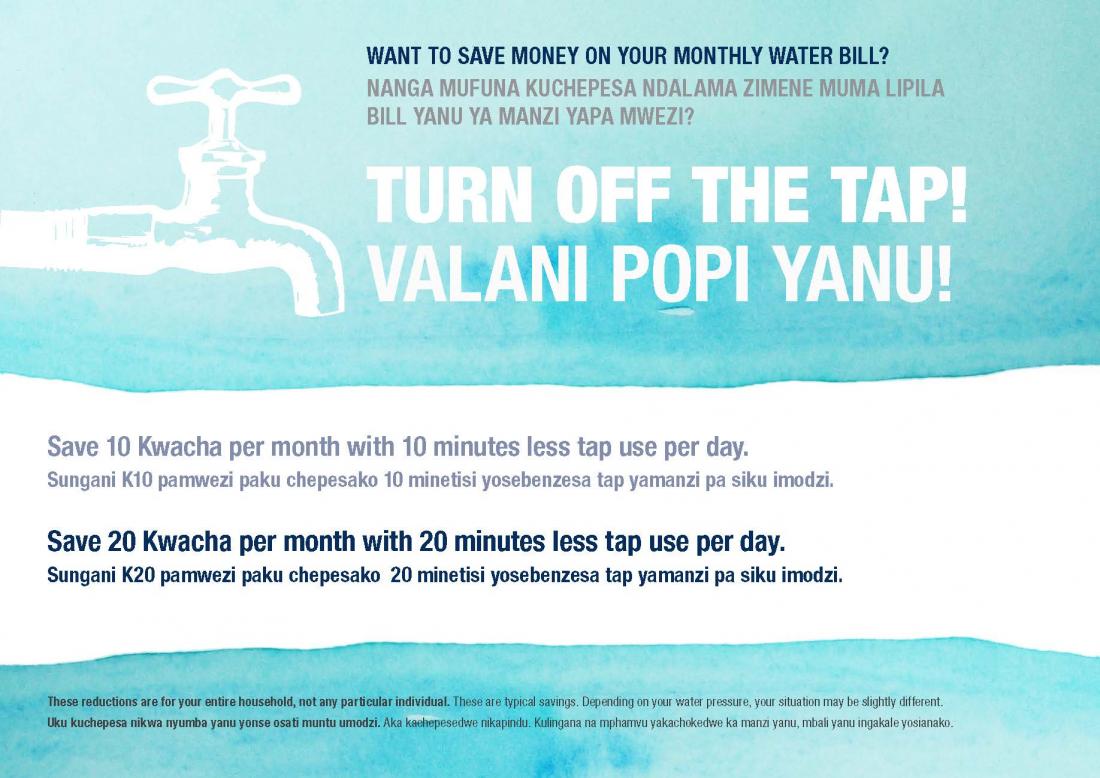

- Price information: All households in the lottery group and plus half of the households who did not participate in the lottery—three quarters of all households in the sample—received simple information about the price of water. Specifically, households were told how much it costs to run the tap for a certain amount of time. This information delivery aimed to ensure accurate and consistent price beliefs across households and individuals.

- Provider credibility: Half of both price information only households and lottery + price information households also received information about the water provider’s commitment to billing households only on actual water usage. Households learned the timing of the billing cycle and how their bill is calculated in the event that a meter reader is unable to read the meter. If households did not believe that bills reflected consumption, the lottery and price information treatments might have been ineffective.

- Comparison: A fourth of households did not receive any new information or incentives.

In addition to SWSC’s monthly billing data, researchers surveyed households between May and December 2015 to collect data on water use, bill payment responsibilities, and other intra-household dynamics. During this baseline survey, researchers also conducted a behavioral game with the husband and the wife to measure how altruistically spouses behaved towards one another. Each person received either ZMW 20 or ZMW 30 (US$2 or US$3) and decided how to allocate this money; individuals elected how much to keep for themselves, share with their spouses, or send to a water conservation NGO. Spouses who shared more with each other may be more altruistic toward one another or may expect to recover from their spouses more of the money they transferred – which served as a reflection of their behaviors towards water use.

Results and policy lessons

Only the lottery + price information intervention reduced household water use. The price information and provider credibility treatments alone had no impact on water conservation.

Households in which only one individual was offered the chance of winning a lottery–a financial incentive— experienced a reduction in monthly household water consumption of 6.1 percent. This impact was even larger among households in which the lottery information was directed to the non-bill payer (most commonly the wife): a 11.5 percent reduction in water use. However, there was no difference in results if the non-bill payer was male or female. This suggests the lottery created an incentive for non-bill payers to conserve; otherwise, these individuals do not financially benefit from saving less water so do not put in enough effort to conserve water.

These results show that an effective way to reduce water consumption might be to target incentives to higher household water consumers, through technologies or in-kind rewards, rather than changing household level pricing.