Increasing college access by making the application process easier

Resumen

There are significant disparities in college enrollment by income. As of 2015, only 12 percent of low-income youth in the United States completed bachelor degrees by age 24, compared to 58 percent of youth from the highest income quartile [1]. The complex college application and enrollment process can be a significant barrier to college access, and low-income students often encounter additional barriers while receiving less school-based support in this process. Researchers have tested a variety of programs designed to provide support at each stage of the college application and enrollment process, such as mailed information about college options, classroom-based or one-on-one assistance, application fee waivers, and text message reminders about enrollment requirements.

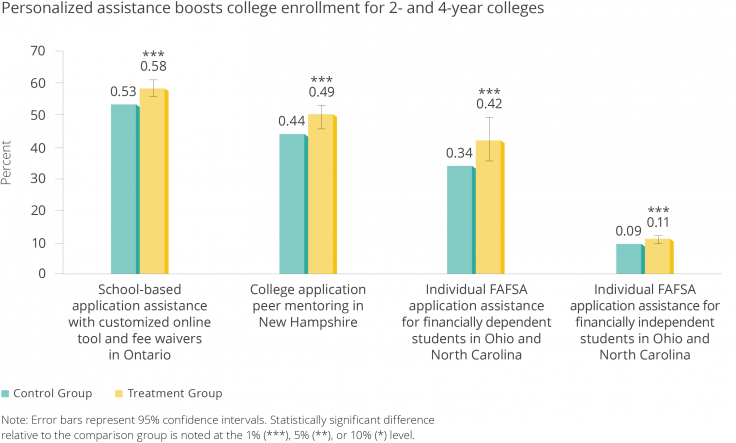

A review of five randomized evaluations of interventions designed to increase college access in the United States and Canada suggests that making the application process easier and more convenient to complete can increase college enrollment and persistence. Interventions that helped students navigate these complex systems achieved significant impacts at relatively low cost. To encourage college-going, policymakers, admissions officers, and educators can simplify the application process, provide personalized support, and waive application fees.

| Step | Barriers | Evaluated interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Develop college-going aspirations and complete required high school coursework | Lack of college-going culture or information about college Social norms that discourage academic preparation |

|

| Select colleges to apply to | Difficulty selecting best-fit schools, especially among high-achieving low-income students | Classroom-based assistance on selecting colleges to apply to Semi-customized mailings about college options |

| Apply to college | Complex and overwhelming application process High application and test-taking fees |

School-based assistance Mentoring Fee waivers |

| Apply for financial aid | Complex and overwhelming application process Uncertainty around eligibility |

Personalized assistance |

| Get accepted to college and matriculate | Additional required tasks for matriculation Unexpected fees, transit costs, and material costs Tuition deposits and delays in financial aid |

Text message reminders Peer mentoring |

In addition to challenges to day-to-day academic success, many specific barriers exist within each step of the complex college application process. Researchers evaluated several programs designed to help students overcome these barriers and succeed in each step of the transition to college.

Lecciones de la Evidencia

Personalized support had a positive impact at each stage of the college process.At early stages of the college process, classroom-based and one-on-one assistance helped students select schools to apply to and complete applications. In Ontario, Canada, school-based application assistance workshops using an online tool, in connection with fee waivers, boosted college applicationrates for graduating seniors by 13.6 percentage points and boosted enrollment rates by 5.2 percentage points[2]. In New Hampshire, individual mentoring during the college application process also increased college-going rates, especially for women.The offer of peer coaching raised college enrollment rates by 6.0 percentage points overall and increased enrollment for female students in particular by 14.6 percentage points[3]. Personalized assistance also played an important role in helping students apply for financial aid. Students whose families received individual assistance from a tax professional in completing federal financial aid forms in Ohio and North Carolina were more likely to file financial aid applications, receive financial aid, and enroll and persist in college [4]. Even after getting accepted to a college and applying for financial aid, students face barriers to college access. Up to 20 percent of students who get accepted and intend to go to college do not end up enrolling. Personalized assistance can help students who are accepted to college in the final stages of the enrollment process, especially for four-year colleges. Outreach from a current college student during the summer before college increased eventual enrollment in four-year collegesby 4.5 percentage points but had no effect on enrollment in two-year colleges in several cities in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania [5]. Three other summer college counseling programs, in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Georgia, similarly increased enrollment in four-year colleges [6] [7].

Providing generic college information alone had no detectable impact on college enrollment.Information on financial aid without personalized assistance in Ohio and North Carolina did not successfully increase FAFSA application submissions, financial aid receipt, or college enrollment [4]. Likewise, letters to New Hampshire high school seniors with college information (highlighting the benefits of a college education and providing a link to the online application), but without fee waivers and direct mentorship, also had no effect [3]. It appears that generic information alone is typically not enough to encourage college enrollment.

Semi-customized information, combined with fee waivers, influenced students’ decisions on where to apply to and enroll in college.While generic information had no impact, customized information helped students select and apply to appropriate college options. Most high-achieving, low-income students do not apply to or enroll at the same schools as their higher-income peers, despite having similar qualifications, and many do not apply to any selective colleges. Customized mailings that shared selective college options, showed predicted college costs, and provided fee waivers led high-achieving, low-income students in the United States to apply to and enroll in selective schools at higher rates. After receiving the customized mailings, students enrolled in colleges with higher graduation rates and higher instructional and student-related spending [8]. Similarly, a customized online tool that provided students with suggested college options based on their grades was a key component of the school-based workshops in Ontario, Canada. A less customized version of the program also increased application rates but had no impact on college enrollment—the customized list of college options appeared to be important in ensuring students applied to schools that they were qualified for and that appeared to be a good fit [2].

Timely reminders with specific action steps, such as text messages about concrete tasks, also boosted enrollment.In Massachusetts and Texas, sending text messages to students, and when possible their parents, to remind them of required tasks increased enrollment in two-year colleges by 3.0 percentage points (from a baseline rate of 20.2 percent). The text message campaign did not influence enrollment in four-year colleges [9]. However, text messages in Massachusetts, Florida, and Georgia improved student completion of pre-enrollment requirements and modestly boosted enrollment [9] [10]. Text message campaigns also increased financial aid applications by a small amount and helped students make informed and active college-related borrowing decisions [11] [12].

Fee waivers were a key component of effective programs.Fee waivers played an important role in boosting college applications and were a key part of the programs like the customized mailing intervention in the United States.Fee waivers made families more likely to find the materials credible and increased the probability that a student would remember receiving the mailed materials [8]. Likewise, when the school-based program in Ontario, Canada included fee waivers, it boosted application and enrollment rates. Without fee waivers, the program had a negligible or even negative impact on applications and enrollment rates [2].

These interventions were particularly effective for students with limited access to college support.Researchers suggest that the interventions that are effective are most beneficial for students with few or no other sources of college transition support. For example, the school-based workshops in Ontario, Canada were particularly helpful for students who lacked confidence academically, did not have parents helping them to apply, or were otherwise disadvantaged [2]. The impact of the mailed information and fee-waiver program in the United States was also larger for low-income students from high schools where few students score in the top decile of college assessment exams [8].

Similarly, peer mentoring by undergraduate mentors during the application process [3], peer counseling during the summer before college [5], and sending text reminders about tasks required for enrollment [5] were most beneficial for students who did not receive college application assistance from teachers, parents, or other sources. In particular, the effects of the text message reminders were largest in Lawrence and Springfield, Massachusetts, two cities with few college access organizations; as compared to the effects in Boston, Massachusetts and Dallas, Texas, two cities with more college application support options.

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). 2018. "Increasing college access by making the application process easier." J-PAL Policy Insights. Last modified February 2018. https://doi.org/10.31485/pi.2327.2018