Evidence-based approaches to tackling recent increases in gender-based violence

Many countries have witnessed a surge in cases of domestic violence due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent stay-at-home orders.

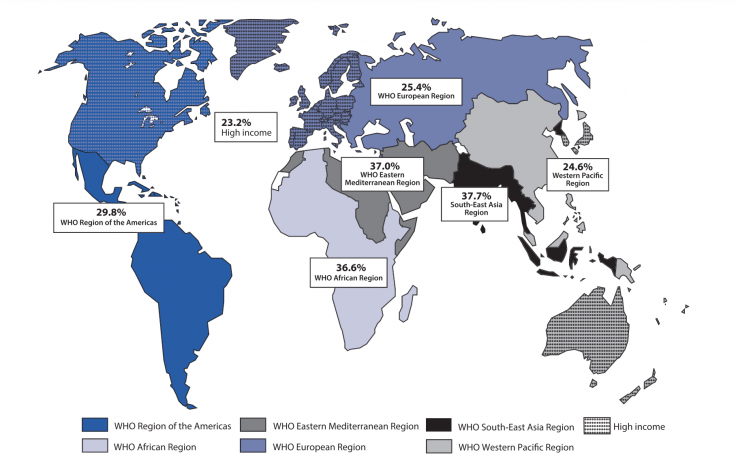

This phenomenon is especially concerning in Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, and Southeast Asia, where rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) are already high. In Africa, we witnessed a similar phenomenon during the 2014-2016 Ebola crisis, which was defined by some as an undocumented rape epidemic.

Now that women are also confined to their homes by lockdown measures, research from the World Health Organization suggests incidences of emotional, physical and sexual violence are likely to increase. The consequences can be dire for women’s mental and physical well-being, even leading to self-inflicted or other-inflicted death.

Governments looking to protect women living in abusive households can turn to the existing evidence for ideas on potential policy measures.

A range of interventions have shown promise in reducing IPV, including:

- Cash transfers which aim to reduce financial stress in the household

- Gender trainings which can change social norms about gender-based violence

- Media campaigns to encourage reporting and change social norms

It’s important to note that none of this research was conducted in emergency settings like COVID-19, so some interventions may not be feasible and results may differ—but by focusing on the mechanisms behind why these interventions were successful, we can still identify important lessons for policymakers to consider.

Cash transfers to alleviate economic stress

Cash transfers have been found to be effective in reducing IPV by alleviating economic stress and increasing women’s power in the home—improving outside options from marriage and giving women means to leave abusive partners. A one-time unconditional cash transfer in Kenya averaging US $709 led to reduced physical and sexual violence when the transfer was made to women and a smaller reduction in physical violence when transferred to men.

Transfers are likely to be more effective if they are extended throughout the stay-at-home period. Evidence suggests that the effects of transfers may not last beyond the period of the transfer. In addition, similar access to resources through microcredit, savings groups, or employment do not lead to sustained impacts in reducing IPV.

Policymakers considering cash transfers should note that they can lead to a backlash and increase IPV (men resorting to violence in order to reassert their authority) if there is no credible threat that the woman could leave the marriage (for example, by having access to job opportunities). A study in Ecuador found that, among less educated women, cash transfers increased emotional violence if women had more years of education than their partner. It should therefore be made clear to women that they can leave their home to seek shelter if they are victims of violence, despite COVID regulations.

In addition, cash transfers should mainly be considered where social protection infrastructure to identify beneficiaries and deliver financial support already exists. IPV interventions will need to be implemented quickly to support women during lockdown. Cash transfers are traditionally difficult to set up; a speedy implementation may be more feasible and cost-effective if mobile cash systems are already in place.

Training and coaching

While more research is needed, several studies have found that training or coaching sessions were effective in reducing IPV. A couples' intervention in Rwanda discussing gender roles and power relations led to large reductions in physical and sexual IPV over the following year.

Training interventions can also be conducted with women alone. A study in India found that twenty participatory health education sessions implemented in self-help groups had positive impacts on women’s self-confidence in refusing sexual intercourse and demanding a condom, reducing the occurrence of unwanted sex.

Combining cash transfers and trainings

Economic interventions have been found in some cases to reduce IPV more effectively when bundled with interventions that intentionally address gender norms, like gender training or family dialogues.

In Côte d’Ivoire, adding gender dialogues to Village Savings and Loan Associations reduced physical IPV for women who attended at least 75 percent of the gender dialogue sessions with their partners. It should be noted that high-attendance couples may have had characteristics that differentiated them from other participants and thus may explain the effects on IPV, but the result still points to the greater effectiveness of bundling than economic interventions alone.

Of course, interventions that are delivered in-person or by bringing people together through community approaches may be more difficult to deliver during social distancing. In addition, it’s important to note that interventions targeting abusive partners individually, for example through text messages, could place women in more danger if the partner believes that they have been reported or are being personally accused.

Mass media and “edutainment”

Recent literature suggests that media and “edutainment” (educational entertainment) campaigns could be effective in reducing violence against women, though more research is necessary. A video series screened to communities in Uganda led to a reduction in cases of IPV. The videos encouraged witnesses to speak out by reducing fears of social repercussions and increased expectations among men that the community would intervene in the case of a violent incident.

Importantly, the study did not change pre-existing social norms around the “acceptability” of IPV, but rather leveraged existing social norms to highlight which forms of violence were not acceptable to the community.

Edutainment may also change social norms around gender violence. In Nigeria, an educational TV series designed to promote safe sex and change attitudes around HIV featured a subplot about domestic violence. Men who had access to the show had a 6 percentage points lower probability of justifying violence, a 21 percent decrease from the comparison group.

More research is needed to understand if campaigns that change social norms also affect behaviors of violent partners. In Tanzania, for example, researchers are currently working to measure the impact of radio programming on gender-related attitudes and behaviors by challenging the legitimacy of violence against women.

Testing innovative policies in a pandemic

In these unprecedented times, policymakers need to develop innovative approaches to protecting women.

For example, J-PAL affiliated researcher Erica Field (Duke University) has been working with the government of Peru to assess whether it’s possible to change social norms by training community leaders on beliefs and stereotypes surrounding gender roles, norms regarding violence, and strategies to identify and prevent GBV.

During COVID-19, the research team has been working to tailor the intervention design to account for limitations to in-person interactions. Researchers are exploring using SMS nudges and other technology to deliver training content remotely.

Using existing evidence to design new programs is important to increase the likelihood that interventions will help victims of intimate partner violence and to reduce the risk of backlash from perpetrators seeking to re-establish the balance of power following well-intentioned interventions.

Integrating evaluation methods will also be important to answer remaining questions:

- What is the impact of targeting men rather than women in IPV prevention programs like cash transfers and training, and can it reduce the risk of backlash?

- How effective is digital technology in delivering gender training, compared to in-person facilitation?

- Can different interventions like media campaigns and empowerment training change social norms and do the results translate into reduced cases of IPV?

To learn more about how to build evidence-based policies that address intimate partner violence or integrate an evidence-oriented approach into your existing policies, read J-PAL’s new women’s agency literature review and don’t hesitate to contact us. J-PAL Africa is working with partners in southern Africa to integrate evidence-based approaches into policy design and would be happy to support other African partners in this work. Please reach out to Alessia Mortara if you are interested.