Why researchers should publish their data

Empirical work in the social sciences often uses primary data collected by researchers, or other data that is not yet publicly available. Researchers spend lots of time and money to collect these data; yet after the publication of the paper, the data frequently sits in their files, rarely revisited and slowly buried, unless it is published and shared.

There has been a growing research transparency movement within the social sciences to encourage broader data publication. In this blog post we share some background on this movement and recent statistics, key factors for researchers to consider before publishing data, and tools and resources to support data publication efforts.

The research transparency movement

The notion of “open data”--the concept that data collected by researchers should be shared publicly without costs incurred by secondhand users--has been promoted by a handful of social science institutions, including the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), the Open Science Framework (OSF), and the Harvard Dataverse, hosted by the Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences (IQSS).

Other interesting projects (like Code Ocean and Two Ravens) have been developed to facilitate replication, data exploration, and analysis of published data. These open data initiatives aim to reduce the costs incurred by researchers in sharing their data.

Many social science journals have supported open data by putting data publication policies in place. Economics and political science journals are most likely to require authors to submit both code and data (Table 1). (Submitted code often takes the form of either the final code file that runs analyses on cleaned data, or a set of multiple files which include the final analysis code as well as code that cleaned the raw data and produced final estimation data.)

Back in May 2016, J-PAL affiliate Paul Gertler, with Sebastian Galiani and Mauricio Romero, authored a paper that looked at articles published in the previous three issues of nine leading economics journals to determine how many articles actually included data publication. The authors found that of 203 empirical papers published, 76 percent published at least some data or code (Figure 1). About one-third of the studies published raw data/code, while two-thirds published final analysis data/code. (Raw data can be more beneficial to other researchers’ work since it often includes more measures than appear in the final analysis.)

Table 1: Journal Policies on Posting Data and Code.1

(Top tier) Economics

(Mid tier) Political Science Sociology Psychology General Science Journals Analyzed 11 23 10 10 10 3 Code/Data required before publication 10 8 8 2 1 3 Code/Data optional/encourages 1 9 0 2 2 0 Raw data must be submitted 10 7 0 0 0 0 Code/Data verified before publication 0 0 3 0 0 0

Note: From a survey consisting of 11 top-tier and 23 mid-tier empirical economics journals as of July 2017.

Figure 1. Share of Studies with Posted Data and Code.

Note: from a survey consisting 11 top-tier and 23 mid-tier empirical economics journal as of July 2017

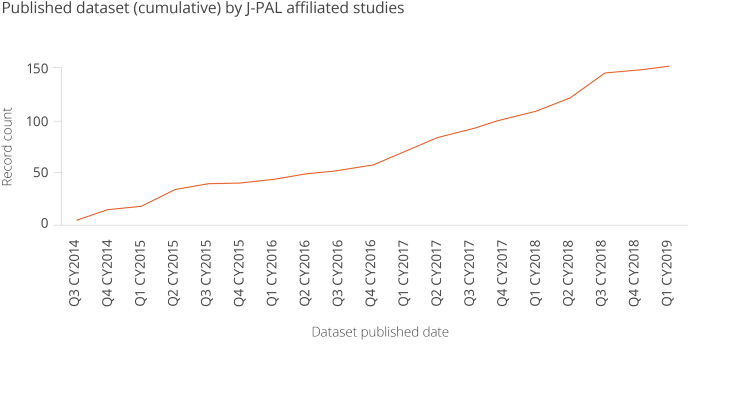

The chart below shows the rapid growth in the number of dataset published by J-PAL affiliates, by quarter.

Figure 6. Published Dataset (cumulative) by J-PAL affiliated studies

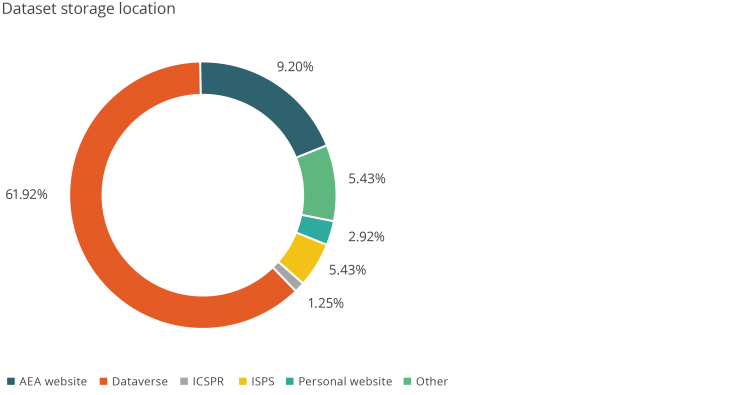

Figure 7. Dataset Storage Location

While these numbers are promising, there is room for growth. Despite journals’ data publication policies, an increasing number of authors are claiming exemptions. From 2005 to 2016, although the proportion of papers with data submitted to the American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings rose from 60 percent to around 70-80 percent, the proportion of papers submitted which received exemptions from the data publication policy rose from 10 percent to more than 40 percent.3

Authors cite confidentiality issues as the primary reason for their inability to publish data, especially for studies that deal with sensitive information. Intellectual property concerns are the second most-cited reason for requesting exemptions to data publication policies.

With these concerns in mind, authors may perceive that the benefits of data publication do not outweigh its perceived costs and risks.

For example, authors may worry that sharing data could result in losing full control of the data , other researchers using the data for similar research when the original author’s paper is not yet published, or perhaps outside parties digging for errors in the data analysis. Private data providers, especially for-profit companies, are often unwilling to relinquish valuable proprietary data to the public out of concerns that competitors might gain from it.

These risks are valid, but can be minimized by managing permission settings for reuse when there are concerns about malicious users, and avoiding misinterpretation by showing transparency in the research methods used.

The benefits of publishing data

There are many long-run benefits to publishing original research data. Open data can increase visibility of the research and number of citations counts. For example, there is some evidence that publishing research articles for open access, rather than behind a paywall, increases citations.4

Similarly, a preliminary paper by J-PAL affiliate Ted Miguel, with Garret Christensen and Allan Dafoe, concluded that papers in top economics and political science journals with public data and code are cited between 30-45 percent more often than papers without public data and code. It is plausible that open data platforms such as the Harvard Dataverse lead to greater visibility for the researcher, as users who browse or download a dataset are likely to see the associated study or paper.

More importantly, open data is a public good. The availability of data benefits not only researchers, but policy partners who supported the studies, students who learn from using the data, and - importantly - the people from whom the data was collected (though much more work is needed to better inform and educate study participants and members of the public on effective use of open data). Even further, open data enables government agencies to use data that otherwise is costly to obtain.

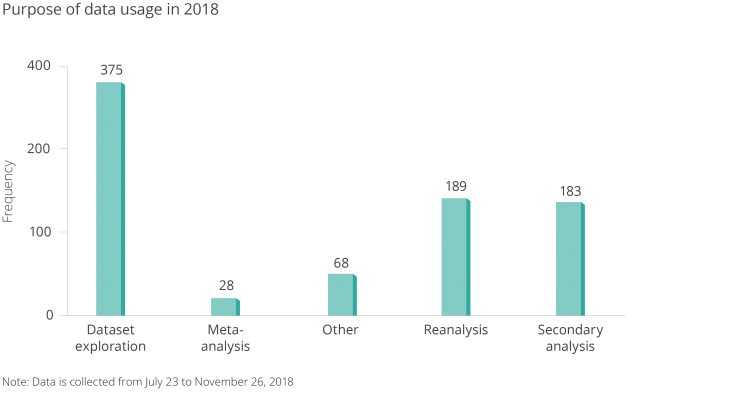

Open data has the potential to generate new ideas and spark new collaborations between researchers and policymakers--but it only serves this purpose when others are actually reusing the data. For example open data becomes a public good when data are reused for:

- Research (reanalysis, meta-analysis, secondary analysis, replication)

- Teaching (curriculum use for presentations and assignments)

- Learning (dataset exploration)

The J-PAL Dataverse, a subset dataverse in the Harvard Dataverse, is an open data repository which stores data associated with studies conducted by J-PAL affiliated researchers.

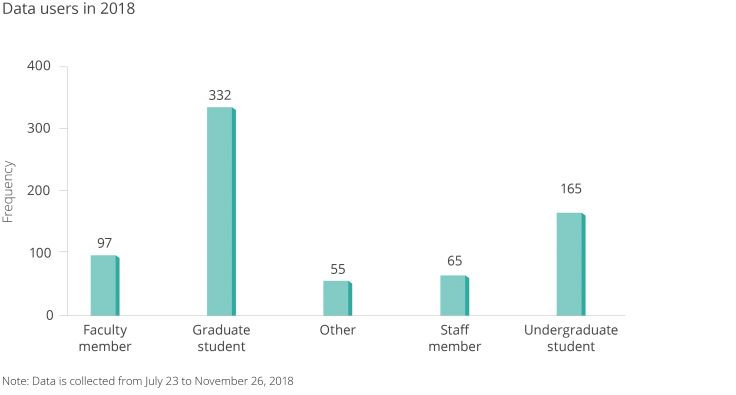

We collected data from our database in J-PAL Dataverse users using a guestbook to better understand who was accessing this open data, and for what purpose.

Figure 4. Data Users of J-PAL Dataverse.

Note: Data is collected from July 23 to November 26, 2018.

Figure 5. Purpose of Downloaded Dataset

Note: Data is collected from July 23 to November 26, 2018.

I’m a researcher--how can I start publishing my data?

You can get credit for your hard work collecting data, and contribute to the public good, by making data public. It is worth the effort: Researchers and others often do reuse data and appreciate the effort that goes into cleaning it and curating the code.

What are important considerations for researchers before publishing data?

- If a donor is funding the research, what are their data publication requirements? Some may require publication of just the data that are part of the analysis, and some may require all data collected to be published.

- If your dataset includes administrative data from a third-party organization, are there any data user agreements in place (DUA) that prevent you from publishing the data? Could you go back to the data provider and talk about publication? If you are you writing a new DUA at the beginning of a project, can you include a mandate for data publication?

- If your dataset includes survey data, does your informed consent clause allow publication? Who did you tell your survey participants that you would be sharing the data with? How did you tell them their responses would be managed? ICPSR has several good recommendations for informed consent clauses.

- Does your institutional review board (IRB) protocol have stipulations regarding data publication? Did you mention data publication as part of your original protocol? Can you go back to your IRB for approval of data publication?

- Where will you publish your data? Are there associated fees with the repository? Does your donor mandate a specific repository?

- How sensitive is your data? Does your data contain information regarding individuals' financial, health, education, or criminal records? If so, have you considered releasing the data in a restricted repository (similar to ICPSR’s data enclaves) where researchers can only access it through DUAs and additional agreements about usage?

- Have you thoroughly evaluated the risk to participants? What efforts have you made to reduce the risk of identifying individuals in the study? Have personal identifiers been removed from the data? Could someone potentially link several indirect identifiers (such as gender, age, and address/zip code) to identify individual in your study?

- For example, in dataset that contains sensitive information about individuals, there is a tradeoff between utilizability of data and the privacy of human subjects. Protecting individuals should be the main priority.

- Are the data and code clearly labeled and clean? Would a third party be able to review, read, and run your code?

- Have you clearly documented how the data is organized, how it was collected, what particular variables or observations were dropped or cleaned, and how to use the data and run the code?

Researchers should have a clear answer for each question prior to data publication in order to ensure ethical and responsible use.

An increasing number of research and donor institutions have listed data publication as a condition for grant funding.

J-PAL’s data publication policy requires evaluations funded by our research initiatives to share their data and code in a trusted digital repository (more details are in J-PAL's Guidelines for Data Publication).

We’ve worked closely with our affiliates on curating their data and code for publication since our efforts to increase research transparency began in earnest in June 2015. This work includes cleaning code, labeling datasets, ensuring that personal information is removed or masked, documenting metadata, and publishing datasets themselves. The J-PAL Dataverse has the benefit (over a regular website like a faculty page, for example) of assigning a permanent digital object identifier (DOI) to a dataset for consistent citation, and storing the data in perpetuity through consistent URLs.

Tools and resources

J-PAL and our partner organization Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) have created resources to help researchers publish their data and improve research transparency. IPA’s best practices for data and code management illustrate good coding practices that can be used to help clean and finalize your data and code before publication. J-PAL North America’s data security procedures for researchers provide context on elements of data security and working with individual-level administrative and survey data.

With this in mind, we’re always working on new resources to support research transparency. Have an idea? Email me at krubio [at] povertyactionlab [dot] org.

To learn more about our work to promote research transparency, visit www.povertyactionlab.org/rt.

References:

Galiani, Sebastian, Paul Gertler, and Mauricio Romero. Incentives for Replication in Economics. Tech. rept. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Christensen, Garret, and Edward Miguel. 2018. "Transparency, Reproducibility, and the Credibility of Economics Research." Journal of Economic Literature, 56 (3): 920-80.

Tennant, J.P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D. C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L. B., & Hartgerink, C. H. (2016). The academic, economic and societal impacts of Open Access: an evidence-based review. F1000Research, 5, 632. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8460.3

1 Galiani, Sebastian, Paul J. Gertler, and Mauricio Romero. “Incentives for Replication in Economics.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2017, 4. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2999062. 2 Galiani et. al, 5. 3 Christensen, Garret, and Edward Miguel. “Transparency, Reproducibility, and the Credibility of Economics Research.” Journal of Economic Literature 56, no. 3 (September 2018): 937. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20171350. 4 Tennant, Jonathan P., François Waldner, Damien C. Jacques, Paola Masuzzo, Lauren B. Collister, and Chris. H. J. Hartgerink. “The Academic, Economic and Societal Impacts of Open Access: An Evidence-Based Review.” F1000Research 5 (September 21, 2016): 632. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.8460.3.